Do People’s Different Beliefs about God Mean They Worship Different gods?

Being mistaken about the right object does not mean referring to the wrong object.

Do people’s different beliefs about God mean they worship different gods?

Many Christians speak as though they do.

Wheaton College fired a professor for claiming that Muslims and Christians worship the same God.

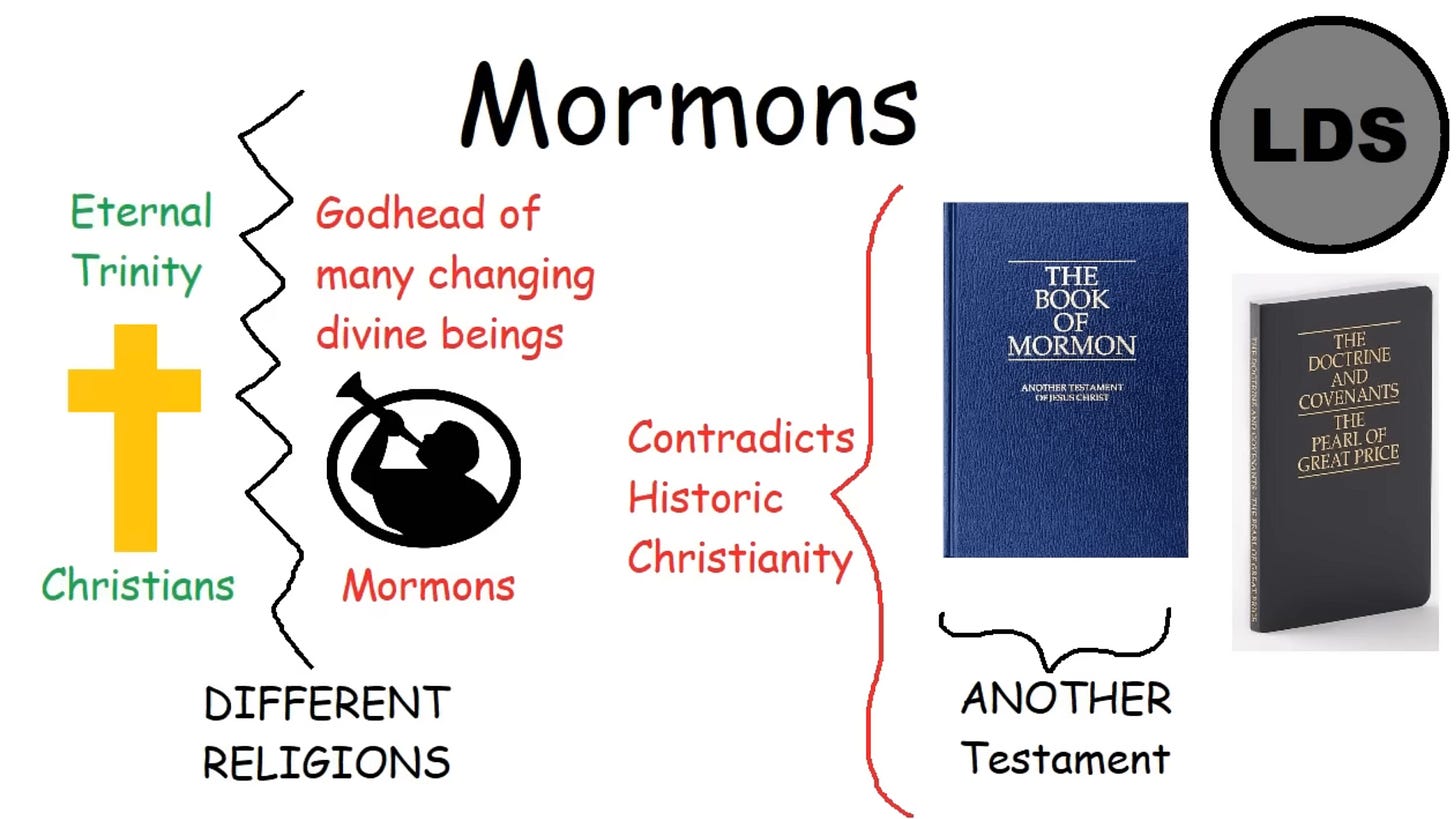

In a recent video, YouTuber Redeemed Zoomer said that, because Mormons and orthodox Christians have different conceptions of God – as an ‘Eternal Trinity’ or as a ‘Godhead of many changing divine beings’ – they “believe in different gods” and Mormonism and Christianity “can’t be said to be the same religion.”

My freshman year at college, I wrote that Catholics and Protestants worship different gods, in an op-ed for the college newspaper.

But the idea that different beliefs imply different gods presupposes a controversial philosophical view: descriptivism about reference.

Descriptivism about reference is an object of critique in my Ph.D. dissertation, following many significant challenges to it in the philosophical literature of the last half-century.

But the chief objection to descriptivism about reference to God is this:

If having heretical beliefs means that one does not refer to God, then those beliefs are not even about God, much less false of Him. But then it is impossible to have heretical beliefs about God.

Hm, that’s not the result we wanted!

To get straight on what went wrong here, let’s dig in to what descriptivism is, the challenges to it, and why it is a poor way to understand theological disagreement.

What Is Descriptivism?

According to descriptivism, when you or I attempt to refer to something, we refer via a description in our minds which an object satisfies.

So, when I attempt to refer to my wife, I refer successfully if an object in the world matches the description of her in my head: “An attractive woman, with a degree in music, and an occupation as a Christian counselor, etc.”

But there are several problems with this theory:

Descriptivism implies that it is a purely conceptual truth that my wife got a degree in music, but my wife could have gotten a degree in business or history.

An example of a conceptual truth is “All bachelors are unmarried.” It is true in virtue of the meanings of the terms. “Analytic,” “tautological,” “logical,” and “necessary” are other terms for this kind of truth.

BUT it is a contingent, empirical truth that my wife got a degree in music, not a conceptual truth. Therefore, I and others must be able to refer to my wife without the mediation of a description of her.

While I may possess a detailed description of my wife, people often refer to individuals and objects they cannot adequately describe.

For example, I can refer to Cicero, even if all I know about him is that he was a famous Roman orator. Given that there were other famous Roman orators, this description is insufficient to distinguish him from others. Yet we successfully refer to historical figures all the time without possessing individuating descriptions of them. (An “individuating description” is one that only one individual matches.)

In fact, that is the normal condition to be in at the beginning of a research project: “I can refer to Cicero, but I can’t describe him. Now, let me find out some information about him.”

We often successfully refer to things of which we have false beliefs or have received misinformation.

For example: I direct you to “the man in the corner drinking whiskey.” But it turns out that he is drinking vodka, if in a whiskey glass. I still successfully referred to him.

It’s like my description comes with a proviso: “Fix it up, if I’ve got the description wrong!”

Likewise, if I falsely believe that Aristotle was the teacher of Plato, as an introductory philosophy student might easily do, the inadequacy of my description of Aristotle does not change the fact that my use of “Aristotle” refers to Aristotle, and my use of “Plato” to Plato.

“Who are you studying?”

“Aristotle, the teacher of Plato — or was it the other way around?”

In fact, that is precisely why my statement is false. Aristotle did not teach Plato. If the inadequacy of my description of Aristotle interfered with my ability to refer to him, then my belief that “Aristotle taught Plato” would not even be false, which it is.

Descriptivism misdescribes the phenomena of reference and description.

Descriptivism about Divine Reference?

Let’s apply these lessons over to theology:

Consider what we could call descriptivism about divine reference.

On this theory, we successfully refer to God only if we possess an accurate description of him. If our description is inaccurate, we refer to a different god ( … or “god,” or something).

But let’s consider the three objections to descriptivism in a theological context:

Descriptivism about divine reference implies it is a purely conceptual truth that God is a Trinity, became Incarnate, etc.

In other words, if you’ve got the right concept of God, you’ll just know that God is a Trinity.

Now, some theologians have defended this, like Anselm, Hegel, Van Til, Frame, and Poythress.

But most people think that you can’t know just by attending to the concept of “God” that He is a Trinity. After all, you might have started with the wrong concept of God.1

At least on the mainstream view, that God is a Trinity is not a conceptual truth; rather, it had to be revealed. Likewise, on the mainstream view, the Incarnation of the Son of God arises from the will of God and so was contingent, rather than necessary and conceptual.

Furthermore, these truths about God do not enable us to refer to God, as if you couldn’t refer to God unless you already knew them. Rather, the ability to refer to God enables us to learn truths about God.

We can refer to God before we can describe God.

If descriptivism about divine reference is true, then I can only refer to God if I have an individuating description of God.

Depending on what you’re after, this is either way too easy or way too challenging.

After all, “the Creator of the universe” seems to be sufficient to pick out God only.

But then, a bunch of heretics and people from other religions are able to refer to God because they also think he is the Creator of the universe.

So we can make it more challenging. We’ll say that you can only refer to God if your description of him is specific enough that only orthodox Christians hold it.

But then, the bar seems to be too high. Kids will, presumably, be unable to refer to God, much less pray to him. Moreover, when adults attempt to teach them things about God, the kids will be unable to believe them about God — at least until they learn enough truths that their use of the word “God” starts to refer to Him.

Whether descriptivism sets the bar too high or too low, it seems that we are able to refer to God even if our description of him is insufficient.

In order for us to have false beliefs about God, our uses of “God” must already refer to Him.

If we want to say that heretics and non-Christians have false theology, their sentences have to at least refer to God.

Take the sentence, “God did not become incarnate.” If “God” does not, in that sentence, refer to God, then on what grounds can we say it is false?

Perhaps “God” in that sentence refers to something else, god1. But then the truth of “God did not become incarnate” does not turn on whether God became incarnate, but on whether god1 became incarnate.

But then, these beliefs are not false. After all, the Mormon god (godLDS) did not become incarnate. (He started as a man and became God — or godLDS.) It may be false of God that he did not become incarnate, but the Mormon belief isn’t about God; it’s about godLDS.

If false theological beliefs do not even refer to God, then false belief is impossible. Heck, heresy is impossible.

But we can refer to the man in the corner drinking vodka even if we misdescribe him. So it follows that we can refer to God without describing him sufficiently, or even accurately.

In fact, my descriptions would not even count as inaccurate unless they were descriptions of God.

Even false beliefs about God are about God.

Even people with false beliefs about God refer to God.

Descriptivism about divine reference misdescribes the phenomena of reference to and description of God.

The Alternative: Direct Divine Reference Theory

What should we think if we abandon descriptivism about divine reference?

In philosophy, the alternative to descriptive reference is direct reference.

According to direct reference theory, the meaning of a term is the thing it refers to, without the mediation of a description.

Effectively, a term tags something in the world, rather than catching it in the net of a description.

For more on tags v. nets, read this:

Is the “Divine Dictionary” View of Language as Bad as Postmodernism?

I received this question on my first post, to paraphrase, “Do you really think that the ‘divine dictionary view’ ‘implies the same degree of imposition on reality’ as the postmodernist view?”

If we adopt a “direct divine reference theory,” then our word “God” refers to God, independently of any particular description we may believe concerning God.

It follows that the true things we say of God are not merely conceptual; they must be learned and received through natural and special revelation.

We can also refer to God even while our conception of God is rather inadequate. This enables us to learn new things about the God to whom we already refer.

Also, children can refer to God and pray to Him, despite limited knowledge about Him.

In the same way, people in religious traditions that differ from Orthodox Christianity, or none at all, may refer to God despite their inadequate conceptions about God.

Most importantly, the only reason their, and our, beliefs about God can be said to be false of God, is that we all successfully refer to Him. Even our false beliefs about God are only false because they refer to God, of whom they are false.

The very possibility of false belief, and even heresy, presupposes that it is possible to refer to God despite the inadequacy of our descriptions or conceptions of God.

So let’s drop the talk about people believing in different gods.

Instead, let’s discuss what is true and false of the God to whom we all successfully refer.2

Watch the Video:

Anselm himself starts with the shared conception of God found in classical monotheism, across Jewish, Islamic, and Christian medieval theologians. He thinks you can deduce the Trinity — and even the Incarnation — from this shared conception of God. So he doesn’t really support the descriptivist view. See the Proslogion for his deduction of the Trinity, and Cur Deus Homo for the deduction of the Incarnation. And, of course, the Monologion for the deduction of the existence of God.

Or, almost all. Some beliefs may be divergent enough that it is difficult to find a term that refers to God. However, most forms of polytheism have a highest god, plausibly identified with God himself. My claims in this article are not meant to prejudge the details in a particular case.

I always think of this problem of reference in relation to the scene from The Lion King in which Timon, Pumba, and Simba take turns describing the stars:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q1O57ZijwPQ

Timon - Fireflies

Pumba - Balls of gas burning millions of miles away

Simba - Past ancestors

Clearly, their descriptions are wildly different, but they are all trying to understand the same objects.

Thank you for this refreshing breath of common sense how much an online world of much finger-pointing. I have heard Orthodox and Catholic commentators claiming that one another’s communions worship different gods, before they even get started on Protestants, Jews or Muslims. Quite mad.