Why I STOPPED Being a Presuppositionalist

And began to be a Christian Humanist

My theological education took place at Westminster Seminary, the bastion of presuppositionalism.

Presuppositionalism: Christian thinking must begin from all and only Christian presuppositions.

And this thesis had a noticeable effect on our studies.

95% of the time we would read people who already agreed with us in order to believe what they said.

5% of the time, we would go find somebody we disagreed with and be assigned to go figure out what was wrong with them.

But after Westminster, I did a program in philosophy at the University of Chicago. In this beautiful, gothic reading room, etched in stone over one of the doorways was this quotation:

“Read, neither to believe nor to contradict, but to understand.”

And those words summed up what had been wrong with my experience at a presuppositional seminary, and what was so right about my experience at the University of Chicago.

Now, my Christian perspective is not just based on Christian presuppositions.

Now, my Christian perspective suggests that even if I’m not looking at the Bible, I see indications of the Divine.

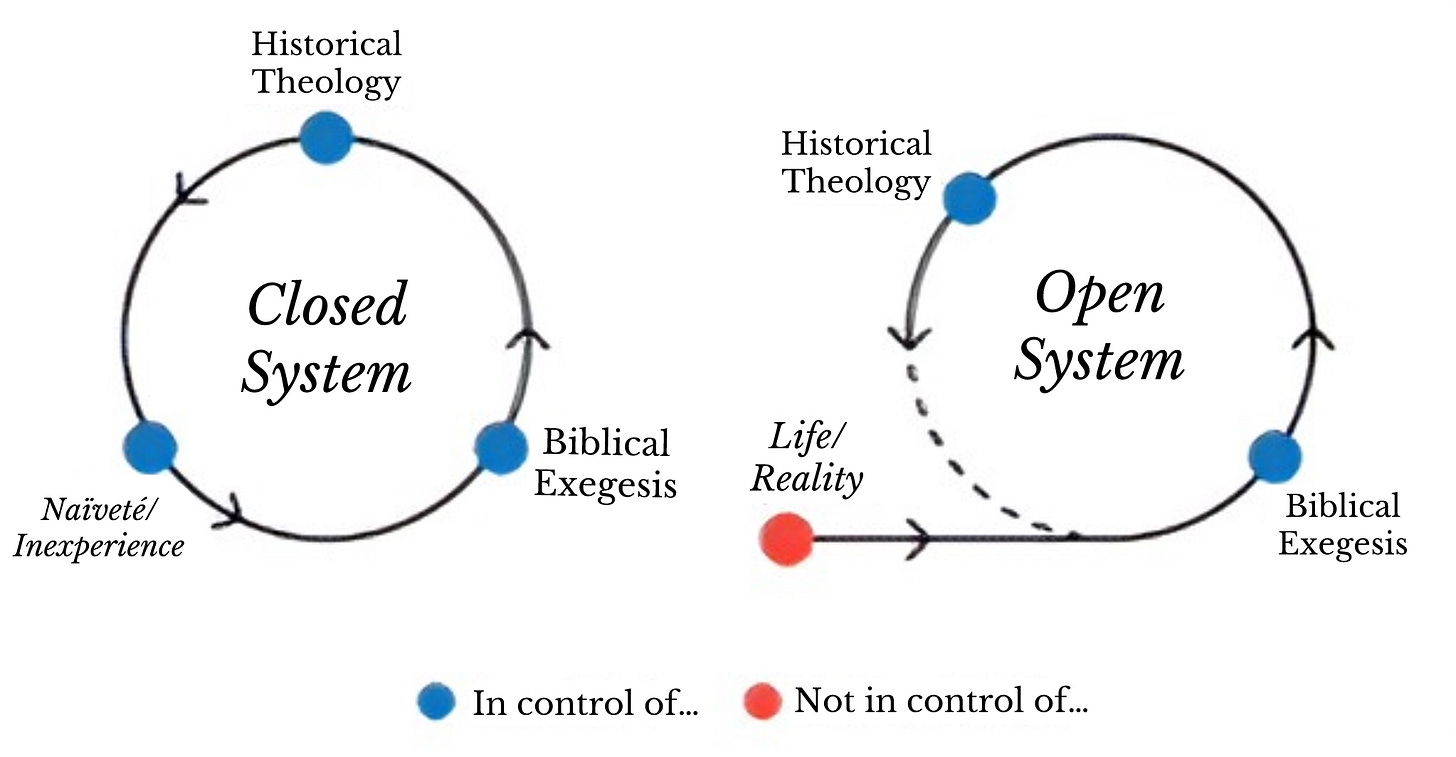

Readers, last week, I argued that the theology nerd mindset is that of a closed system, a self-reinforcing circle of Bible and theology, with no outside inputs.

While much evangelical theology makes this error implicitly, presuppositionalism endorses and radicalizes this error explicitly.

The presuppositionalist avows that theology should utilize circular arguments, beginning all and only from Christian presuppositions.

And even if you haven’t encountered presuppositionalism, I think you’ll recognize the tendency to ideological thinking that refuses to be challenged and protects its ideas from outside interference.

Not so the Christian humanist. Outside interference, from reality, is what the humanist desires.

That’s why the story of how I stopped being a presuppositionalist is also the story of how I became a Christian humanist.

In the rest of this post (originally a YouTube video I made in February), I tell the story of how I stopped being a presuppositionalist. Thank you for reading.

If you want to learn more about transcending the theology nerd mindset, sign up for my upcoming (July-August) course, From Theology Nerd to Christian Humanist.

I. What Is a Presuppositionalist?

The story of how I stopped being a presuppositionalist begins back when I was one.

A presuppositionalist is someone who believes that, to have a consistently Christian worldview, you need to start from all and only Christian presuppositions.

The underlying theory is that people of different worldviews all start from their own presuppositions. If you’re a materialist atheist, you start from those presuppositions. If you’re a Christian, you start from a Christian set of presuppositions, and never the twain shall meet.

Nobody really bases their beliefs on just an objective look at the evidence. We all bring a set of lenses, interpretive schemes to the world, and a Christian ought to make the Bible their interpretive scheme.

Now for me, this was compelling as I was first taking my faith seriously. I’d had a lot of time where I just was a Christian on Sunday, and I didn’t know how to apply my faith to the other days of the week. That’s a lot of people.

But as I was trying to take that faith more seriously, reading the Bible more, studying theology—the idea of having Christian presuppositions for all that you do sounds really compelling.

I was also getting into the Reformed theology space where there’s an argument put forward that presuppositionalism is the consistent Calvinist or Reformed approach to apologetics, instead of classical or evidential apologetics, where you start from common ground and evidence to argue to a Christian worldview.

Now I remember going off to college, at a Christian college. I thought, “Hey, I can get a Christian perspective on things!”

And my now wife showed me her homework from a philosophy class, and it was about Thomas Aquinas, who is the opposite of a presuppositionalist. He’s a natural theologian. And he was arguing that there’s a distinction between the preambles of faith, the things you can know apart from faith or revelation, and the articles of faith, the things that are taught by faith.

Aquinas would say that the Trinity, the Incarnation, and redemption you can only get from the Bible. But that God exists, that there is a moral law, and that we’ve sinned, these things can be known apart from Scripture. They might be even what gets you interested in Scripture. If you start to think, “I think there’s a God out there. Maybe I should read this Bible people keep talking about.” That’s the preambles versus the articles.

But I denied that. I remember at the time thinking: “No, everything’s got to start from the Bible. That’s how you’re going to have a consistently Christian perspective on things in the world.”

II. The Turning Point: Moral Attitudes in P. F. Strawson

But there was a time in a final philosophy class I took at that college, we were reading about free will and moral responsibility.

And there’s an important essay by Peter Strawson, British philosopher from the mid-20th century—“Freedom and Resentment.”

In it, Strawson was arguing against the hard determinists. These are philosophers who think that free will and determinism are incompatible, that determinism is true and that therefore free will is false.

And the hard determinists thought that therefore, we should rid ourselves of all emotions that assume that other people are moral response morally responsible. Think, e.g., resentment, from the title, that assumes that the other person has free will and purposefully did something to you. Or gratitude on the positive side: to be grateful towards somebody assumes that they were free, deserving of praise for what they did, and not just, “Well, they were pre-programmed to do it.”

And Strawson’s argument took an interesting form, because Strawson was not a Christian. He was not somebody who argued that we have a soul or a metaphysical basis for free will, that we're not physically determined by our psychology or something.

No, he just said, “There’s no way that we’re going to rid ourselves of these emotions of resentment and gratitude, blame and praise. These are part of being human, that we are equipped with the ability to make these evaluations.”

And so from there, he said, no metaphysical thesis that pointy-headed philosophers or physicists come up with in the lab is going to affect this practice and its validity. If you bump into me, what decides whether I should be mad or forgiving is whether you intended to do so, not whether physicists have figured out whether quantum mechanics is true.

So that idea, I didn’t realize it, but that was already incompatible with presuppositionalism.

How? you say. How was Strawson’s idea incompatible with presuppositionalism?

Well, let’s take an example of a presuppositionalist argument. A prominent one was the way Doug Wilson debated Christopher Hitchens in their recorded debates.

Wilson is officially a presuppositionalist. (He’s got some other C. S. Lewis, natural law influences that we’ll leave aside for the moment.)

But Wilson kept pressing Hitchens on Hitchens’ morally fervent critiques of the God of the Old Testament and the New. He would say, “Where do you get this morality by which you can judge—by what standard can you judge that God is evil, for having the Israelites go and kill the Canaanites? By what standard can you judge that penal substitutionary atonement is morally repugnant? You must be assuming a moral standard that has no place in an atheistic, materialist universe.”

Now there are two ways you can go with an argument like that. The presuppositionalist essentially says:

“You, atheist, have no basis for morality. Stop it. You need to be consistent. Go become a nihilist and go kill other people or yourself.”

That’s the extreme version, but that’s essentially, “Go take your presuppositions to their logical conclusion.”

But that’s not the direction that Strawson goes.

Strawson is not a Christian, but he’s saying there’s something else beyond metaphysical inklings (i.e., do you believe in God or materialism).

There’s our ingrained human ability to evaluate things on a moral level and to feel the emotions that are part and parcel of that.

And that’s not going away.

To read and understand Peter Strawson’s article, sign up for From Theology Nerd to Christian Humanist. I’m adding it to the syllabus for “philosophy week.” Grab a copy of the syllabus by clicking this link.

III. C. S. Lewis and my Agnostic Professor

And that’s actually where C. S. Lewis starts his argument for Christianity, in the very opening pages of Mere Christianity.

C. S. Lewis says people are doing this all the time. They’re saying, “That’s mine!” “Don’t take that.” “You pushed me.” “I didn’t mean to!” They’re arguing in these moral terms based on these practices of praise and blame that we all already participate in.

And C. S. Lewis says, “We all already know about that, but that thing is a clue to the meaning of the universe.”

So both the presuppositionalist and the natural theologian hold that you can’t make sense of morality without God, but they do different things with this claim.

The presuppositionalist says, “You need to be consistent and give up on morality.”

The natural theologian says, “You need to be consistent with what you already know—that morality exists—and adopt a worldview that explains why the world is more than just material.”

The presuppositionalist says, “There’s no common ground between believer and unbeliever; there’s nothing we have in common. All that morality you’ve got is, at best, stolen capital. You don’t have a right to it.

The natural theologian says, “Of course, you have a right to that. That is your birthright as a human being.”

And now we’ve got common ground together, and we can look at the world, given our shared morality and say: “Well, what makes the best sense of this? Does evolution explain morality, or does it just explain why it's advantageous for weaker people to obey morality? Would it make better sense to believe that God is at the foundation of morality, or would that make morality arbitrary, as if God could command something different?”

These are the philosophical questions that morality and theology raise, but the natural theologian acknowledges that there is common ground between believers and non-believers on that basis.

Now, if we fast-forward, I’m in a position with my dissertation advisor, in a philosophy program, where he’s an atheist, or an agnostic rather. But he’s also a moral realist. He really does believe in morality.

Do I want him to be consistent with his atheism and be more amoral and nihilistic?

No, I’d like him to be consistent with that morality. I think he’s absolutely correct about what he’s seen in the world that gives him this sense of morality. I just think his evolutionary explanations of it fall short.

There’s more to this world than that in order to explain morality. The normative cannot be reduced to or explained by the natural.

IV. Westminster: Presuppositionalist Seminary

Now, from Wheaton College, I went on to Westminster Seminary, the bastion of presuppositionalism, where Cornelius Van Til taught of old, the chief presuppositionalist thinker.

And there I learned a lot. There was a robust curriculum, so much to be thankful for. But there was also presuppositionalism in almost every class.

And presuppositionalism, starting only from your own presuppositions, had an interesting effect on our studies.

It meant that if you wanted to learn something about any topic, you wanted to read something from someone who shared your worldview. So if you want to learn about mathematics, you need to go read a book like Redeeming Mathematics by one of our professors. You need to read a book from your worldview. If you want to think about laundry, you need to read a Reformed theology of laundry, and so on, to reach the absurd.

But leaving that aside, there was a tendency to just read our own perspectives.

95% of the time, we would read people who already agreed with us in order to believe what they said.

5% of the time, we would go find somebody we disagreed with and be assigned to go figure out what was wrong with them.

And I got dissatisfied with this at a certain point. I thought, “I already know that the people who agree with me agree with me. I’d like to learn from people who disagree with me. In fact, I’d really like to know whether anybody out there who isn’t a Christian thinks that some of the things we’re saying are true, or do they think we’re just totally crazy. They don’t have to agree with us on every point, but do they see some of what we’re saying about moral reality, about right and wrong, about the importance of faith and religion, the limits of science and so on?”

And in my own studies, I began to find that there were such people. The philosopher Roger Scruton was one I discovered. Jordan Peterson was coming on the scene. I saw him doing the same thing.

V. The University of Chicago: Humane Academy

And so, from Westminster, I decided to go get a master’s in philosophy.

I did a program at the University of Chicago, which was a 180 from Westminster. It was people of all different beliefs studying together in a much different way. There was no assumption that people shared their points of view. There were good ideas, bad ideas, but it was an open environment to think things through and come to your own conclusions.

In this beautiful, Gothic reading room at the University of Chicago, etched in stone over one of the doorways was this quotation:

“Read, neither to believe nor to contradict, but to understand.”

—words of Francis Bacon, the great Christian scientist-philosopher.

And those words summed up what had been wrong with my experience at a presuppositionalist seminary, and what was so right about my experience at the University of Chicago.

At the University of Chicago, no one told me what to think. At the University of Chicago, I was reading people who didn’t share my presuppositions, and yet finding them making cogent and coherent arguments, and not in an exclusively atheistic or materialist direction, but carefully navigating the terrain of human thought, the merits of a more moral view of the world, the limits of a scientistic view of the world.

And I thought this experience was beautiful, and the real result of it was that now my worldview was not just based on the Word of people who agreed with me. In fact, now it was confirmed by people from outside the fold, if you will.

But more than that, I now had things that I could say to people outside my faith that built common ground, but that pointed in the direction of belief. I had arguments that didn’t just sound like an apologetics argument, that there’s a truth to morality that take the philosopher John McDowell, that there’s limits to the purely scientific worldview, that you start to lose our grip on ourselves as beings with minds and moral knowledge.

And all of those things could be said without asking somebody first to adopt an entire biblical worldview.

VI. Conclusion: Christian Humanism and Empiricism

And so what was the result of this change of heart and change of mind?

Well, it led to me taking a perspective that I now call either empiricist or humanist.

Humanism is often the bad thing in a kind of Christian worldview discourse. “Watch out for secular humanism!”

But there’s a long tradition of Christian humanism, of which C. S. Lewis was a part, Thomas Aquinas, many of the Protestant Reformers who were humanists, following Erasmus (like Zwingli!), and they believe that there’s a lot in secular learning that we can take. We can plunder the Egyptians, as Augustine says. Philosophy can be a preparation for the gospel, as Clement of Alexandria and Justin Martyr among the Church Fathers said.

And empiricist, in that now, I believed that the human faculties of our senses and our reason could get things from the world and learn new things. We didn’t just need to download biblical presuppositions, put on our Christian goggles and see the world through that.

We could see the world. Unmediated information from the outside gets in, because God made us to know this world. (See my “Toward a Sophisticated Realism.”

What that’s done is it’s strengthened my Christian perspective. Now my Christian perspective is not just based on Christian presuppositions. Now my Christian perspective suggests that, even if I’m not looking at the Bible, I see indications of the Divine. I see reason to believe that there’s a moral reality to life.

I learned that from Christian thinkers who are natural theologians; and I learned it from contemporary thinkers like Jordan Peterson and Louise Perry, who see truth to moral to the moral claims of Christianity. I am not just stuck in my self-enclosed Christian circle of circular arguments.

I think this shift in perspective can really develop our ability to talk with people outside the faith. We need, in this day and age, to be able to talk to people we don’t agree with on the basis of the things we do have in common.

There’s a kind of parallel between presuppositionalism and radical forms of ideology, where, if you don’t agree with everything, I say, we’re in total disagreement.

No, your neighbor, whatever they think, you and they should be able to find some common ground. And from that you can build towards truth together through common truth seeking and a common good that you share.

(I wrote and recorded a pop-punk song about it:)

I’d like to see Christians be more an example of that and and that is part of the reason why I stopped being a presuppositionalist.

Feel free to add a comment if you disagree. I’d love to hear why people still find presuppositionalism compelling, or why you’ve left it behind perhaps, or never held it.

But for now, I’m Joel Carini, the Natural Theologian. Until next time.

Watch the Original Video

Take My Course: From Theology Nerd to Christian Humanist

Want to learn how to become a Christian humanist? Click this link to receive the syllabus for my upcoming course, From Theology Nerd to Christian Humanist:

By signing up, you’ll also receive further information about the course and the invitation to enroll. My current plan is to run the six-week course in July and August this summer, but sign up to get the details over the next couple of weeks.

For more on the subject, read the foundational article of the course:

From Theology Nerd to Christian Humanist

Dear reader, in this post, I introduce the theme of my upcoming course, “From Theology Nerd to Christian Humanist,” a six-week foray into the limits of theology and the breadth of human experience.

It’s invigorating to hear a critique of a philosophy I love so much. Thank you.

But it strikes me that your interpretation of Presuppositionalism is more Kuyper than Van Til.

(You can correct me it I’m wrong- I discovered Presup while attending RTS-Jackson rather than learned it verbally from CVT or Frame at WTS)

Okay, you asked for disagreement, here goes. Two questions for you: (1) of all the supernaturalisms competing for the crown of Single Source of Truth, how is an alien who lands here in 2025 to pick the one to engage with? (2) as someone who believes in objective morality, list its top 10 universal precepts, agreed by all others who aren't in your sect but are also objective moralists.