From Theology Nerd to Christian Humanist

A Roadmap (and a Course)

Dear reader, in this post, I introduce the theme of my upcoming course, “From Theology Nerd to Christian Humanist,” a six-week foray into the limits of theology and the breadth of human experience.

At the end of this article, you will find the link to receive the free course syllabus and future updates about the course, including the invitation to enroll.

Something has changed within me. Something is not the same.

So says the Wicked Witch of the West at the outset of the curtain-closing number “Defying Gravity,” from the musical Wicked.

But the phrase does just as well to describe the transformation I believe I have experienced over the last decade and a half.

It is also a transformation I hope to occasion in others through my writing and my upcoming course.

What follows is a six-step roadmap from the shuttered vantage of the theology nerd to the open vista of the Christian humanist.

i. a new perspective

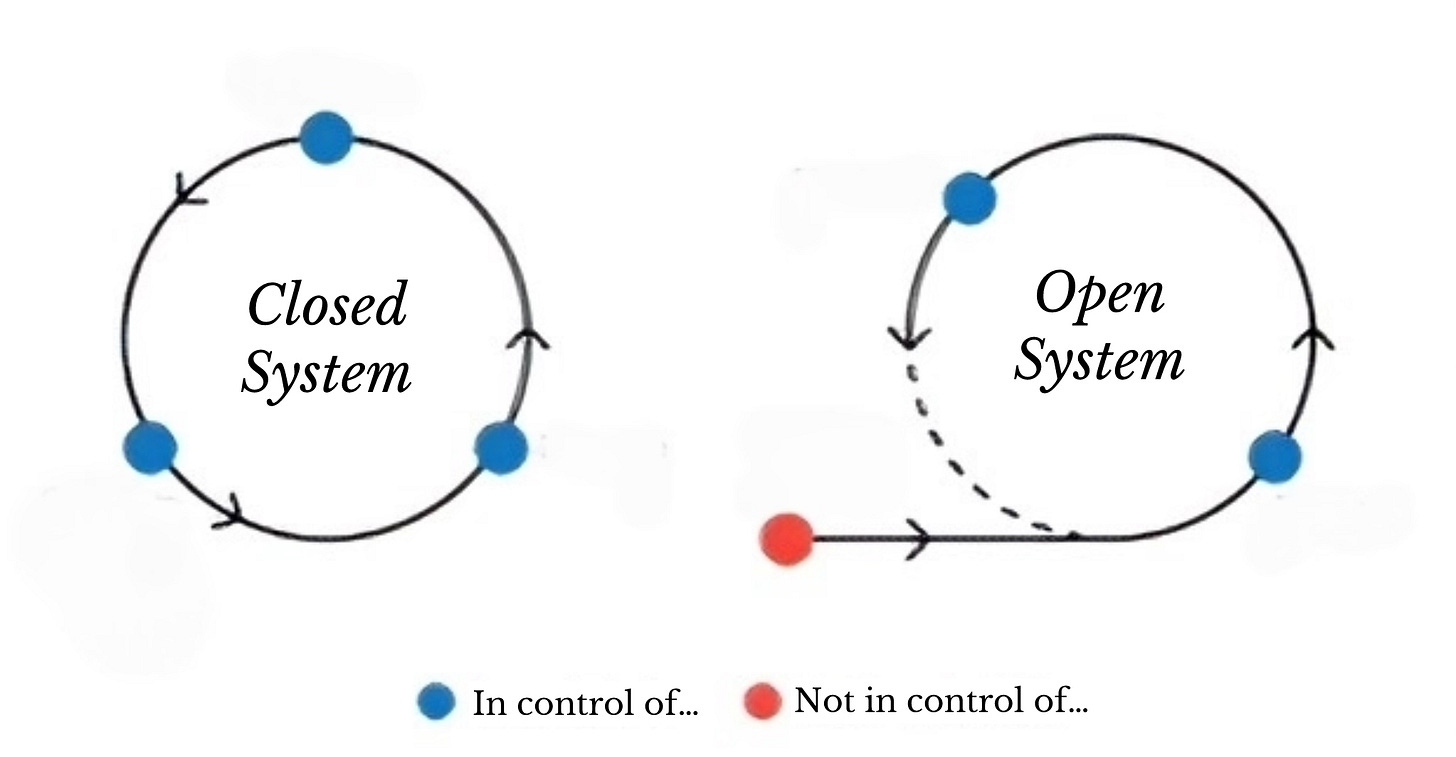

The outlook of the theology nerd comprises a closed system.

If you just know your theology, you can answer all theology’s questions.

Therefore, theology nerds set themselves the task of mastering a finite domain of knowledge, usually either biblical studies or systematic theology.

For any of the questions of theology and the Christian life, a biblical or systematic theology of x should provide an answer.

Theology is a closed system, like chess. There are a limited number of moves. They are determined by the specific game being played. Nothing from the outside can interfere.

If an earthquake knocks down all the pieces, no move has been played and the game can go on, at least in principle.

Not so in theology. The first moment of humanism is the moment when reality knocks down your theological game-pieces.

Maybe at first, you simply realize that biblical study requires historical context or Ancient Near Eastern backgrounds.

Next, you realize your theology of gender roles cannot ignore the philosophical debate between social constructionism and essentialism.

Finally, you realize your Christian theology of parenting is perfect — except that your kids have a thing called a developmental psychology.

In this moment, you realize that anything and everything can interfere with the task of theology. Your biblical perspective, perfectly proof-texted, is thrown off the rails by reality. Your Christian worldview meets the world.

You gain a new perspective: Theology is an open system. Christian thought must be open to the world.

You’ve taken the first step toward being a Christian humanist.

ii. read to understand

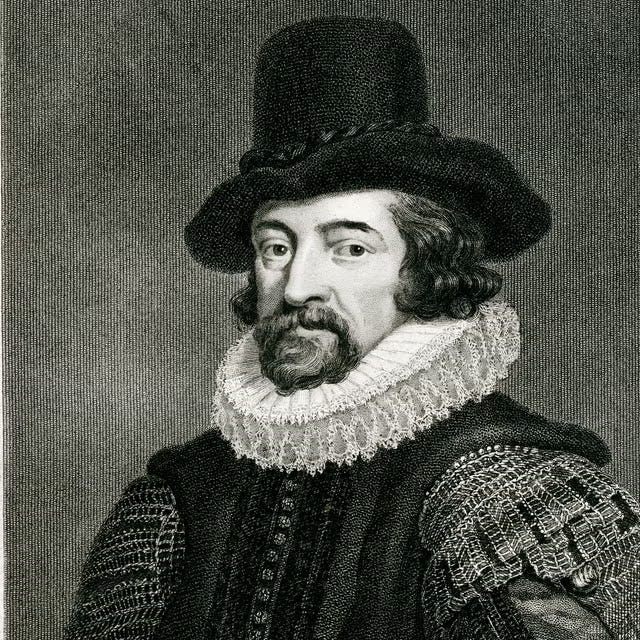

“Read, not to contradict nor to believe, but to weigh and consider.”

— Francis Bacon, “Of Studies”

The theology nerd reads to believe and, every now and then, to contradict.

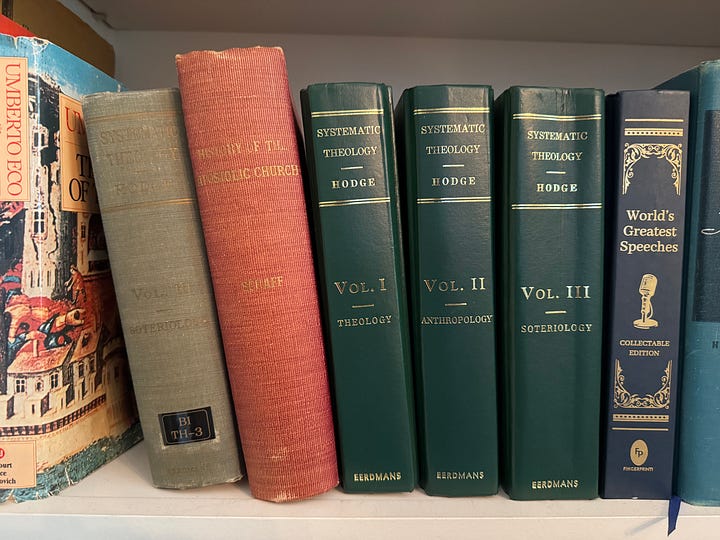

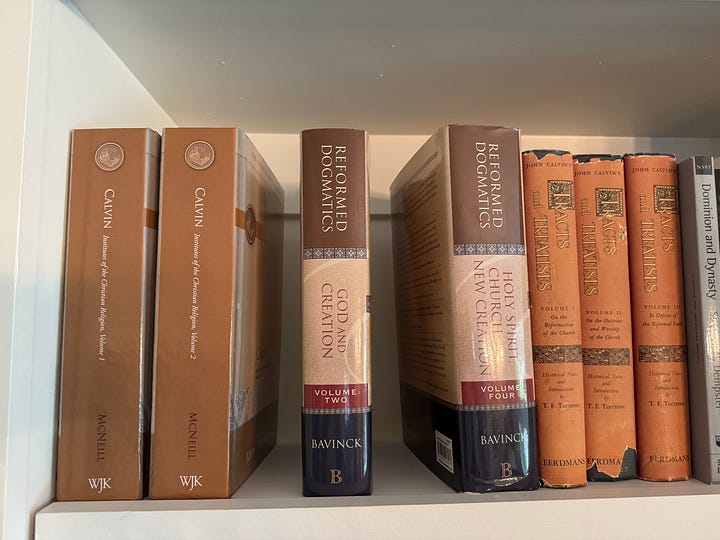

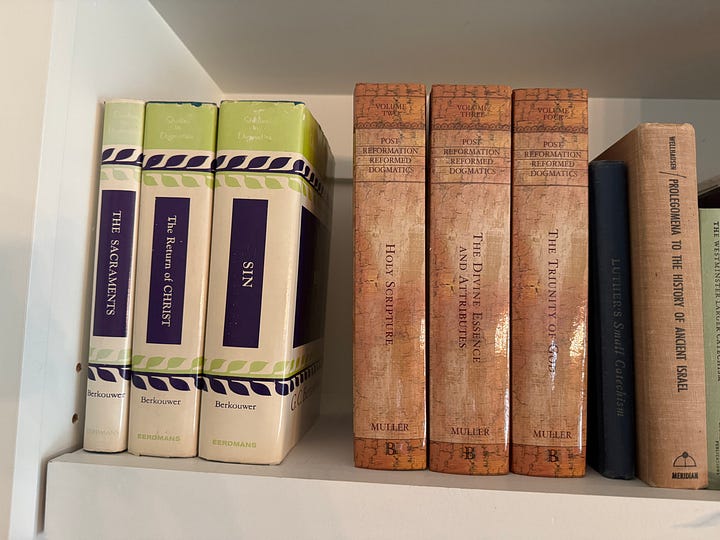

His bookshelf is lined with books from three or four publishers, all of which are selected for their agreement with the theology nerd’s existing beliefs.

Not so the Christian humanist.

The Christian humanist must, first, read books from disciplines beyond theology and biblical studies.

Add to your theology philosophy; to your philosophy, history; to your history, literature; and to your literature, evolutionary psychology.

In reading books outside the discipline of theology, one also reads authors who are not curated by shared belief.

You are not reading to believe — to reinforce and confirm your existing beliefs — but to expand your grasp of reality.

If the author writes something questionable, you do not anathematize the book but seek to understand why she thinks what she does, and to reconsider your own beliefs or rediscover why you maintain them.

Along the way, you encounter one of the most valuable kind of secular intellectual: the fellow traveler.

With no ulterior motive to discover things consonant with Christian theology, the fellow traveler stumbles upon a preamble of faith.

“I did end up … reaching Christian conclusions almost against my will.”

— Louise Perry, in a recent interview

The point of reading other perspectives is not merely to reinforce one’s own. But discovering the fellow traveler is one of the unforeseen joys of Christian humanism. By understanding their perspective, your deeply-held beliefs transpose from doctrines of faith to deliverances of human experience.

And even in reading our intellectual opponents, fragments of reality shine through, refracted through divergent experience. No perspective, however limited and warped, fails to illuminate some corner of what is.

The Christian humanist reads, no longer to believe or contradict, but to understand reality.

iii. study experience

The theology nerd scoffs at experience: “That’s just your subjective experience.”

The Christian humanist is a student of experience.

And while there is a subjective dimension to experience, experience is not reductively subjective. If I relate a story about what happened to me, that anecdote describes objective reality. If you deny that objective reality, you are the subjectivist.

Furthermore, personal anecdotes are the beginnings of empirical science. After all, the plural of anecdote is data.

Humanists, Christian or no, from Bacon to Emerson, have urged humanist scholars also to be students of human experience. So, Bacon:

“To spend too much time in studies is sloth… They perfect nature, and are perfected by experience…

“And studies themselves do give forth directions too much at large, except they be bounded in by experience. … That is a wisdom without them, and above them, won by observation.”

Francis Bacon, “Of Studies”

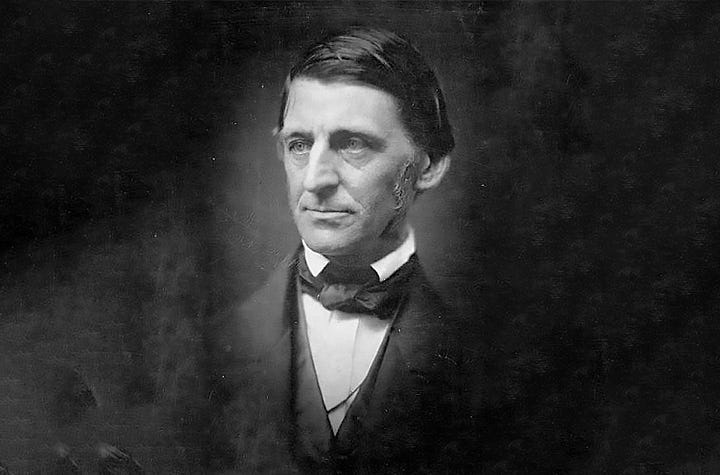

And, Ralph Waldo Emerson:

“Only so much do I know, as I have lived. Instantly we know whose words are loaded with life, and whose not. …

“Time shall teach him, that the scholar loses no hour which the man lives.”

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The American Scholar”

The theology nerd is, of his nature, untrained by experience. The qualifications for a theology nerd are no more than an avid appetite for theological podcasts and blogposts.

At most, a four-year masters of divinity.

The student of human experience, on the other hand, hardly matriculates until his academic education is complete — on account of the peculiar protection from “real life” commonly afforded by academia.

He never graduates.

Experience comes in at least three varieties: Direct, vicarious, and scientific.

Direct experience is our own experience of life. It cannot be gained without years.

Vicarious experience is gained by our knowledge of other people, by history and biography, by novel and screenplay.

Scientific experience is gathered by skill and expertise, organizing the variety of data-points to formulate general statements, grounded in empirical evidence.

Openness to experience cannot be selective among its three varieties. If I admit that I learn from my own experience, I must admit that another human might learn very different things from his experiences. These I must accommodate in my own worldview. And scientific data-gathering is but the intentional systematization of the breadth of human experience.

Nor can you favor science to the exclusion of personal experience, preferring facts to feelings. After all, the facts about human feeling are among the data of the objective world.

The Christian humanist is open to the breadth of human experience, of facts as well as feelings.

iv. the tragic sense of life

Without experience, the theology nerd, like every other young ideologue, is an idealist.

For the idealist — secular or religious, conservative or progressive — the evils of life are problems, in principle, solvable.

The persistence of such problems must be down to a lack of will.

French philosopher Chantal Delsol writes:

“No life is without its difficulties, which were once called troubles (soucis) and which today we call problems (problèmes). This change in terms is not entirely innocent.

“A trouble is something that gives rise to worry, something that torments. A problem, since Greek times, designates a question of geometry or logic. One bears a trouble and solves a problem.”

— Chantal Delsol, Icarus Fallen

Only the person who has encountered the difficulties of life, and discovered them to be, not merely problems but troubles, can be a humanist.

The theology nerd believes, not explicitly but implicitly, that the problems of life would be solved if everyone held purer doctrine.

But the Christian humanist recognizes that theology, like philosophy, can at best provide only consolation in this vale of tears.

The tragic conditions of existence mean that most people will not adhere to our theological system. If the fruits of study are to aid them, we must reach beyond the bounds of our Christian subculture.

Human limitations mean that a holy life will not be free of sin or desire. A holy life is one in which sin and desire are overcome by the turning of the will toward God.

Indeed, in the lives of many, the work of the Spirit may look quite imperfect, even impure.

But, equipped with a tragic sense of life, the Christian humanist approaches his fellow man with understanding and not condemnation.

v. classics and contemporaries

The Christian humanist is not merely an antiquarian.

While we read our Plato, Aristotle, and Aquinas, we remember that Plato, Aristotle, and Aquinas, not to mention Bacon, Descartes, and Leibniz, were eminently contemporary philosophers in their own time.

A contemporary humanism is not merely a kind of classicism.

The Christian humanist must engage the contemporary philosophical and political conversations. His mind must incorporate the contemporary sciences, including psychology and social science, in addition to perennial philosophical questions and classical philosophical and historical sources.

The theology nerd who advances to interest in classical works but discounts contemporary science and philosophy is not yet a Christian humanist.

While philosophy may be perennial, science is progressive.

And while the past holds treasures, humanism must be practiced in the present.

vi. enter the human game

Christians often think that mainstream journalistic, scientific, and political publications are secular.

But we misunderstand this secularity.

To publish in The Atlantic, for example, it is not necessary to hold the same metaphysical or political views as its editors. (Even if such disagreement can prove an obstacle.)

It is necessary to address one’s work to an audience that includes the wide swath of humanity, on topics of public concern, grounded in sources of evidence that are widely accepted.

Likewise, to be an Ivy League philosopher, it is not necessary to be an atheist. (Even if it is common.)

It is necessary to leave one’s religious or metaphysical beliefs unsaid and to address issues of common philosophical interest on the basis of generally accessible philosophical arguments.

The secularity of such discourses consists in their appealing only to our common humanity.

The Christian humanist has a lesson to learn here. He must form his beliefs not only in ways designed for parochial Christian discourse, but also in ways universally human.

Non-Christian authors and commentators do not get to deduce their beliefs, or argue their case, from Scripture. They must fight for knowledge by reporting, study, and wide reading. They must persuade by appeal to evidence, experience, and common ground.

In other words, many of us Christians — especially the theology nerds — are playing “the Christian game.” We remain on the sidelines of “the human game.”

Both in our understanding of the world and our living of life, the Christian humanist seeks not only to play “the Christian game,” but also to play the human game.

Even more, to a great degree, the Christian game is but the human game. The Christian life is a human life. Grace restores nature.

If you only speak Christian-ese, intake Christian media, read Christian books, spend time with Christian people, etc., you’re playing only the Christian game.

The final, culminating step of Christian humanism is to begin playing the human game or, really, to recognize that you already are.

Would you like to become a Christian humanist?

This July and August, I’ll offer a six-week course, From Theology Nerd to Christian Humanist.

Meeting once a week for a two-hour Zoom seminar, the course will consist of guided readings across theology, philosophy, literature, and science. In it, I’ll cast a vision of a new type of Christian intellectual.

Click the link below to receive the course syllabus, further information, and the invitation to enroll.

And a brief word from me:

I love this. There are the equivalent of theology nerds in far too many secular spheres; I'd rather talk with a Christian humanist any day.

Interesting article, Joe.

A topic that has come up for me recently is darwinian evolution, how would you handle that if your child asked you 'is darwinian evolution true?'