Sexual Orientation Is Not a Social Construct

“Gay Christian” is a legitimate term because some Christians ... are gay.

In 2014, Al Mohler announced that he had changed his mind on homosexuality.

No, he had not determined that homosexual marriage was compatible with Scripture, nor that any form of sexual expression outside of heterosexual marriage was divinely sanctioned. He had changed his mind on the existence of sexual orientation.

Formerly, Mohler had written, “Actually, the Bible speaks rather directly to the sinfulness of the homosexual orientation — defined as a pattern of sexual attraction to a person of the same sex.”

Now, Mohler said, “Early in this controversy, I felt it quite necessary, in order to make clear the gospel, to deny anything like a sexual orientation. … I repent of that. I believe that … a robust biblical theology would point out to us that human sexual, affective profiles–who we are sexually is far more deeply rooted than just the will. If only it were that easy.”1

While few might know this, Mohler’s change of mind represented a return to a model of Christian leadership championed in the mid-twentieth century by leaders like C. S. Lewis, Francis Schaeffer, Billy Graham, and John Stott. (Greg Johnson argues this centrally in his Still Time to Care.) In their thinking, writing, and speaking about homosexuality, each of these leaders acknowledged the deep-rootedness of homosexual desire. Their pastoral response was one of care rather than cure.

Social Constructionism the Wrong Foundation for Side B

In interacting with folks in the celibate, gay Christian (Side B) community, I find myself wanting to make their theological case to our more theologically conservative brethren. Often, their arguments are very strong and simply bear repeating in a new context. But on some points, I fear that Side B goes wrong in defending itself, in ways that will only result in it falling on deaf ears.

One of these instances is the adoption of a social constructionist view of sexual orientation. At the 2023 Revoice conference, I got to attend the live recording of the Communion and Shalom podcast, titled “‘You Keep Using that Word…’ - Greg Coles & Erin Phelps on How Sexual Orientation Is Socially Constructed.”

During that podcast, the speakers made the case that “sexual orientation” is a category that developed in the 19th-century, rather than a timeless part of reality. As a category, it is pragmatically helpful in describing experience, but it is not a real thing in the world.

I understand the appeal of social constructionism to Side B. Many of the teachings of American evangelical Christianity turn out, after a generation, to be more culturally-constructed than biblically-derived. This was a source of the appeal of postmodernism to my fellow students at Wheaton College as well. If some teachings, beliefs, and concepts are socially constructed, it’s tempting to hold that all of them, including the concept of sexual orientation, are as well.

But I think this will be an ineffective way to argue the Side B case. Christians who hold that you shouldn’t use the phrase “gay Christian” (Side Y) agree that “sexual orientation” is socially constructed - by secular Freudians and cultural Marxists. Christians aren’t “gay” or “straight”; the only biblical categories are male and female, and anyway, we should find our identity in Christ.

The best case for Side B to make is this: Sexual orientation exists. It’s a real thing. While Side B experience has shown that some evangelical ideas are more culturally-conditioned than biblically-derived, it also reveals that some things are real, among them, sexual orientation. In turn, this means that “gay Christian” is a legitimate term because some Christians are gay.

Sexual Orientation Is Real

Let’s go straight to the heart of things. What is the evidence that sexual orientation exists? There is evidence from personal experience, anecdotal evidence, as well as systematic scientific evidence.

While a postmodern perspective often speaks about subjective experience, I think it important to insist that experience is not merely subjective. How someone feels or experiences things itself is an objective part of the world. Now, that feeling or experience can be mistaken in how it represents the world, including the subject him or herself. For instance, some studies of sexual orientation are done by self-report, others by measuring genital response. (I won’t be commenting on the morality of that method of gathering information.) Someone might report being only aroused by the opposite sex, but studies of genital arousal reveal arousal to images of both sexes. This shows that personal testimony can be mistaken, but the fact of self-perception as well as the actual facts about the person are all real facets of the world.

Importantly, scientific studies are not different in character from personal testimony. They are more rigorous and comprehensive ways of gathering information about people from personal experience. All of these forms of evidence-gathering are valid, if fallible.

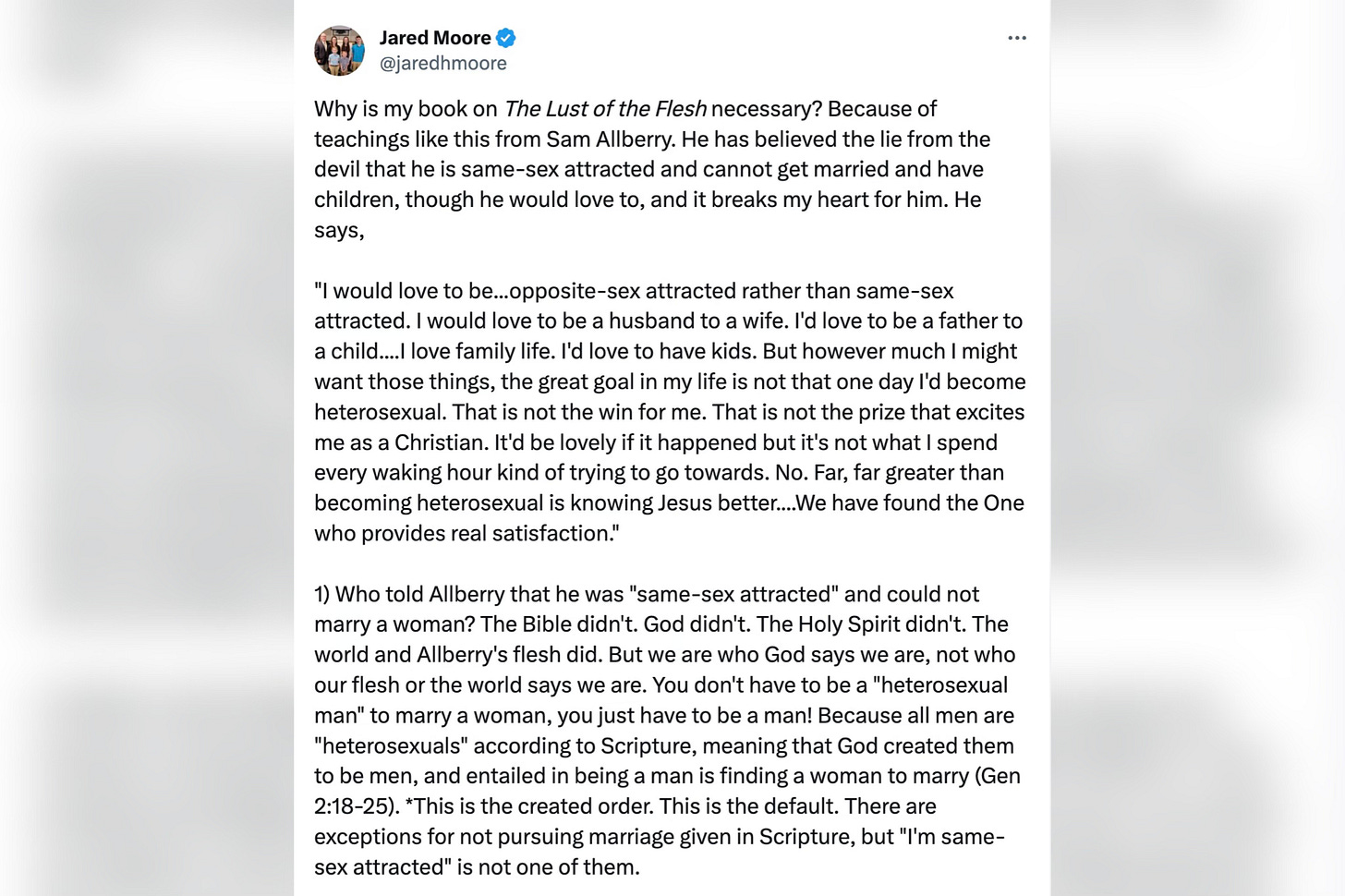

That out of the way, it is legitimate to find evidence of differences in sexual orientation from personal testimony and experience. The same-sex attracted individual who experiences attraction to one sex and not the other has all the evidence he or she needs to prove that he or she has a sexual orientation. (Here is an example of Jared Moore, a Southern Baptist pastor and author of the forthcoming The Lust of the Flesh, denying that Sam Allberry has sufficient evidence to conclude that he is same-sex attracted.) By the same token, the experience of exclusive heterosexual attraction is sufficient to prove that such a person has a heterosexual orientation.

Evidence from personal experience and testimony can be checked, verified, and can increase in sample size through social science. Plenty of studies involving self-report find a significant minority who are homosexual, usually between 2-6%. More interesting, if less comfortable for some Christians, are scientific studies that measure sexual orientation by genital arousal in response to sexual stimuli. These studies find that men are predominantly exclusively aroused by images of their “preferred sex.” One study I read added that the inclusion of someone of the non-preferred sex, even in intercourse, did not increase or even decreased sexual arousal. For example, a heterosexual man is aroused by pornography featuring a female only; the addition of a male does not increase but, if anything decreases arousal.

However, the statistics for women are quite different. Women are generally aroused by pornography of either sex, except for homosexual women. Homosexual women exhibit a more male-typical pattern of arousal primarily (if not only) to their preferred sex. If anything, this suggests that men and lesbian women have a sexual orientation, while “heterosexual” women have a more “fluid” or bisexual sexuality.

On the other hand, given other differences in male and female sexuality, the more visual and physical focus of male sexuality, I don’t think arousal in response to explicit images is the best test of female sexuality. Given the greater emotional focus of female sexuality, the better measure of a woman’s sexuality would be her reaction to men and women as they are in normal circumstances (i.e., clothed). By that measure, a woman would be heterosexual if attracted to men, even if viewing of pornography of either sex could elicit arousal. I don’t think a woman’s heterosexuality needs to be dinged because if you put porn in front of her, it has an effect.

What is more, if anything, the fact that heterosexual women less frequently exhibit exclusive arousal would not indicate the lack of a sexual orientation but rather a bisexual orientation. In any case, it is evident that people’s sexual appetites have particular objects, determined by sex. This means that they vary in accord with a particular variable: Sexual orientation.

Someone who wants to deny that this indicates the existence of sexual orientation might appeal to the purported changeability of this feature. However, even if this feature is changeable, it does not cease to exist. The ex-gay movement, for example, believed in the changeability of sexual orientation. This explicitly means that they believe in the category of sexual orientation, they just thought that it was changeable. It is Side Y only that denies the category of sexual orientation.2

By the way, there is very little evidence of successful orientation change from the ex-gay movement. The primary thing that occurred was a change in how people referred to themselves, a matter of language, rather than psychological change. Greg Johnson spells this out very dispassionately in much of Still Time to Care. I urge readers to consider his history of the ex-gay movement rather than continuing to believe that sexual orientation can be changed by such ministries.

One time, on Twitter, I saw the view denying sexual orientation spelled out almost consistently. Interacting with a gentleman, he argued that all of us have temptation for both sexes, so purported “homosexuals” must just be fanning the flames of the wrong set of temptations.

I wonder what this says about him in particular, but I know that that is not my experience of heterosexual orientation and Christian faithfulness. As C. S. Lewis said, homosexual sin is “one of the two (gambling is the other) which I have never been tempted to commit,” adding, “I will not indulge in futile philippics against enemies I never met in battle.”3

I think that all of this evidence is best experienced through reading the narratives of people who experience same-sex attraction, chief among them, Wesley Hill’s Washed and Waiting. Then read Greg Coles’ Single, Gay, and Christian. Finally, Greg Johnson’s Still Time to Care tells the history of the ex-gay movement in vivid detail, showing how rare or inaccurate reports of sexual orientation change were.

Evidence of Social Construction?

The claim about social construction comes from at least two places: 1) the recent coinage of the term in the 19th century, and 2) the way that sexuality developed differently in other times. In the podcast, David Frank and Greg Coles provide a fine history of the introduction of the term “homosexual,” and its shift from a terminology for sexual addicts to a terminology for a certain kind of person with a certain kind of disposition. Michel Foucault is another source of this kind of historical telling of sexuality, in which he features the shift from an act-based theory of sexuality, in which Christendom talked about sodomy and sodomites, to the psychological and Freudian invention of “the homosexual.”

Then there is the fact that ancient Greek and Roman men seem to have had a very different kind of sexuality then modern men. The standard pattern of male attraction at the time seems to have been for women and young men, with young men taking the cake.4

Several things are going on here. In the first case, we have shifts in the terminology and the way people think and talk about sexuality. We also have developments in knowledge and the science of seuxality. And in the second case, we have real differences in people in different social and historical contexts. I do not believe that the language of “social construction” is the best to help us understand what is going on here.

For instance, with Greek and Roman male sexuality, we have evidence that human sexuality can actually develop differently in different times and places. The point would be that these are real differences in the world, no matter how developed. It is possible that thinking and talking about sexuality in certain ways can begin to influence people’s actual sexual development. But while this would show that intellectual discourse and social considerations can have a causal influence on sexual development, it would be a stretch to say that it showed that sexual orientation was socially constructed. The language of “social construction” implies the unreality of the product.

On the other hand, the development by society of new words does not mean that what the words refer to has been socially constructed. On the one hand, sometimes new words are introduced because a new thing has been discovered. I warrant that sexual orientation is something that has been discovered in the last 150 years, with the caveat that these kinds of differences were not unknown in ancient times. Their scientific formulation in recent times involves accurately identifying a real facet of human psychology.

At the same time, the shift from act-based ways of discussing human sexuality to disposition or types of people-based ways of discussing sexuality is not insignificant. But again, “social construction” is a bad word for this. For instance, we could still debate whether “sodomy” is a helpful word for homosexuality. I see some folks on Twitter trying to return to this older language, calling homosexual sex “sodomy” and homosexuals “sodomites.”

The problem is that “sodomy” does not refer to homosexuality but to anal sex (with a member of either sex). And Scripture does not make mention of the particular details of this sexual act apart from the sex of the parties, so the term “sodomy” is unhelpful. The moral teachings of Christianity individuate sexual activity by the sex of the parties, not the orifices involved.

This means that the shift involved from “sodomy” and “sodomites” to homosexual activity, homosexuals, and men who practice homosexuality is much more relevant for the purposes of Christian ethics. This in spite of the secular scientific origin of the language of homosexuality and sexual orientation.

A Biblical Category?

The objection that comes is a bit too late: “But ‘sexual orientation’ is not a biblical category!”

Having just summarized the empirical evidence of sexual orientation, I wonder if those who object would offer the same objection to a scientific article providing evidence of stomach cancer. “But ‘stomach cancer’ is not a biblical category!”

The fact is that the Bible does not give an exhaustive account of the natural world, including of the fallen condition. The Bible offers no exhaustive list of diseases; this does not mean that the biblical category for diseases is “leprosy,” on account of it being mentioned in Scripture.

The Bible teaches that we live in a created but fallen, natural world, but it leaves observation - whether our own eyes, common human experience, or natural science - to fill in the details. As I have argued before, disallowing the use of certain words to describe the misery of our condition, even the way that original sin has warped our desires, is not especially biblical. In fact, it leads to calling “sin” what the Bible would acknowledge as “misery,” effects of the fall and the curse. The insistence that we only use biblical categories is, in the end, quite unbiblical.

Calling Us What We Are

For celibate, gay Christians, it is quite important to articulate the way that sexual orientation is a real feature of experience, and not one obviously subject to change. And this is the real danger with the language of social construction for sexual orientation: It implies both that sexual orientation is not real and that it can be easily changed. After all, if being same-sex attracted is socially constructed, we could just deconstruct it and reconstruct something else, much as the ex-gay movement tried, and failed, to do.5

Likewise, if sexual orientation is more or less determined by what society calls them, then celibate, same-sex attracted Christians could just heed the Side Y instruction to call themselves “Christians” without a modifier and to refuse to “identify” as gay.

But on my view, celibate, gay Christians may call themselves gay because some people really are gay. The word “gay” in celibate, gay Christian is nothing but an accurate description of that person, a perfectly appropriate adjective. Whether someone “identifies as” gay is quite beside the point. We do not get to opt into or out of identities at will; rather, we can and must use words to describe the world and ourselves as we are.

This “realism” about sexual orientation has an important implication: To tell a same-sex attracted person not to call him or herself “gay” is to tell him or her to dissimulate, to pretend, to lie - to be a hypocrite. This is the real risk of ignoring the category of sexual orientation, of saying that it is an unbiblical category. In doing so, we require people to pretend to be other than they are. We imply that how they are is too shameful to be acknowledged. We gaslight them about how God has made them, the cross he has chosen for them to bear.

If our Christianity requires a whole class of people to hide features of themselves and pretend to be other than they are, I fear that it reveals that we do not believe God could save people who were really and truly broken, whatever our professed theology.6 By the same token, like the Jewish Christians of Galatia, it indicates that we think that some feature of our sexual physiology or psychology qualifies us, and disqualifies others to be saved - for us, heterosexuality, for them, circumcision.7

On the contrary, there is no ground for boasting. Whether your sexual desires align with the created order, or they do not, we are all equally unworthy of salvation:

Let not the foreigner who has joined himself to the Lord say,

“The Lord will surely separate me from His people.”

Nor let the eunuch say, “Behold, I am a dry tree.”

For thus says the Lord,

“To the eunuchs who keep My sabbaths,

And choose what pleases Me,

And hold fast My covenant,

To them I will give in My house and within My walls a memorial,

And a name better than that of sons and daughters;

I will give them an everlasting name which will not be cut off.

Isaiah 56:3-5Quoted in Greg Johnson, Still Time to Care, 137.

TJ Espinoza and David Frank, the hosts of Communion and Shalom, pointed this out to me.

Johnson, 5, from Surprised by Joy.

See the Platonic dialogues, in which desire for women is hardly discussed, while the beauty of male youths is prominently discussed.

Greg Johnson details the whole history of the ex-gay movement in Still Time to Care. I know many folks still think that the ex-gay movement was a success and that people can change their orientation; please read the book.

Johanna Finegan calls this a “theology of glory.”

Misty Irons connects the Side B discussion to the Jew-Gentile Christian issue toward the end of this interview.

I've wanted to comment for a while on this series because I think it's thoughtful, though I'll acknowledge my ideas aren't fully formed on everything you present, while I agree on some and disagree on others. I'm not an expert of any sort on this matter, but I'd still like to present some thoughts:

1. A distinction probably needs to be drawn between observing the observable vs. imitating the language and assumptions of a highly politicized anti-Christian movement. Yes, some arguments you address appear to reject the obvious reality of homosexual desire. But I'm still wary of adopting worldly language that carries certain poisonous assumptions.

The word "heterosexual" is, I think, more politicized than the word "homosexual" for this reason. The mere usage of the word "heterosexual" suggests a value judgment, equating it with homosexuality rather than identifying the ordinary state and the disordered state. If we look at a psychological disorder, let's suppose a relatively value-neutral one, like autism or OCD, we haven't adopted words to describe people who lack these disorders. Likewise, if we have a sexual orientation, should we also say that we have an orientation vis-a-vis OCD? I'm reluctant to adopt this entire way of thinking.

2. I agree that there are Biblical categories here, and then there are sociological/psychological categories, which are still relevant if we want to understand the world. The popular grouping of various sorts of homosexual desire has the potential to erase the diverse psychological reality. This is at least partly motivated by activist political and social concerns (i.e. banding together in a larger LGBT+ alliance and community). Though as you point out, Scripture also groups together multiple sorts of homosexual activity, so I'm torn as to how relevant this is to theology. But I think it's still important to acknowledge and to overcome certain misunderstandings and errors.

3. I want to highlight the peculiarities of obligate male homosexuality in particular, because I think it's too often conflated with all other sorts of homosexuality. To a greater degree than the others, it seems to have deep biological causes. Properly speaking, I think it meets the medical definition of a "syndrome", as it's highly correlated with not only obvious characteristics like feminine behavioral tendencies from an early age, but also seemingly unrelated characteristics like left-handedness and smaller stature, probably also a tendency towards a lisp (though this can often be corrected with speech therapy).

Another curious feature of this syndrome is that the majority of such men prefer to be "bottoms". This is seldom spoken of in the wider world, and I suppose I took for granted most of my life that the "top" was the preferred role -- that their homosexual desire was merely a matter of misplaced "targeting". But I think the preference for "bottoming", and also for more masculine men, suggests a very deep change in the brain's sexual wiring compared to most other sorts of unusual sexual behavior.

Further, it's an error to take the experience of obligate male homosexuality -- the most clearly and deeply biologically rooted sort of homosexual behavior and desire -- and apply it to all the others, regarding "sexual orientation" as unchangeable and condemning the very idea of conversion therapy.

For example, it appears to be far more common (if not quite universally true) that lesbianism is rooted not in some syndromic and inborn disorder in brain wiring, but in a trauma-induced aversion to men. Jackie Hill Perry, who wrote, "Gay Girl, Good God", seems to fit this category, and I think both sides misuse testimonies like hers. It's an error to imply EITHER that obligate male homosexuality can be overcome in the same manner as trauma-induced lesbianism, OR that trauma-induced lesbianism is nearly as difficult to overcome as obligate male homosexuality. But most arguments on both sides have a tendency to take this form.

Greetings.

I've been personally looking into various writings by those on Side-B, both out of personal interest and for private projects I am working on. Your post is recent and you have replied to basically every comment, so I figured I'd reach out as well.

Jed prompted a query about the phrase "pedophile Christian." I bring this up for two reasons. One is that you did not answer his question. Second is that I am one of those Christians who experiences an attraction to children, specifically little girls, and would like to clear up misconceptions and make a query of my own.

Firstly is that, although it is used in that manner colloquially and by exploitative news outlets, "pedophile" in the proper medical sense refers to someone with a sexual preference for children. Much in the same way "homosexual" has been used to refer to those who act sexually with the same sex, but properly used refers only to the disposition to such things.

Secondly is that the willingness of people like me to publicly admit to having such attractions is not relevant to anything. You know the consequences of admitting to something like that. I'm hardly being a coward using a pseudonym here, and neither is anyone else with these attractions.

Thirdly, the way you spoke about this to Jed is demeaning. You put "orientation" in scare quotes when describing pedophilia, implicitly gatekeeping the term to exclude those like me. Then you say, "On the other hand, a great many normal, lovely people have unchosen same-sex desires." Implying me and those like me are necessarily neither normal or lovely, which is incredibly unfair. Last time I checked, I didn't choose pedophilic desires any more than those with same-sex desires chose their proclivities.

As to my own query...

Would it, by your own standards, consider it appropriate for me to refer to myself as a "girl-lover Christian?" And not a "pedophile Christian;" I balk at being referred to as "a pedophile" the same as a gay Christian would chafe at being called "a homosexual." And "pedophile" would not accurately specify the sex of those I'm attracted to. Beyond that, my own preferences and proclivities are irrelevant, as I'm asking you to apply your proposed principles to my situation.

For some clarification, phrases like "girl-lover," "boy-lover," and "child-lover" are what people with pedophilia often use to refer to themselves, much like how those with adult same-sex desires often call themselves lesbian, gay, or bisexual. These in my experience are more popular outside of an activist context than "minor-attracted," let alone "pedophile."

So, I reiterate, would it appropriate for me to refer to myself as a "girl-lover Christian" by the standards you and those in Side-B propose for "gay Christians?"