Presuppositionalism rightly diagnoses the problem. But it offers the wrong prescription.

The remedy is an ancient, academic discipline...

It looks like I have hope of graduating with my Ph.D. in philosophy this academic year.

While I’m up catching a bit of air between deep dives, I’d like to share one of my main motives in writing this dissertation.

By the way, I recently had my first viral note, on the subject of dissertation-writing.

The Presuppositional Predicament

My writing over this summer centered on the critique of presuppositionalism and the theology nerd mindset. In response, I have been invited to do several interviews on this topic, the most recent being with Aaron Renn. (Interview forthcoming!)

In the interview, Renn expressed a defense of presuppositionalism, one that I commonly hear in response to my critique:

“But don’t a lot of worldviews and perspectives come down to unjustified presuppositions?”

And I must admit, with Renn and the presuppositionalists, that this is so.

For example, many atheists assume a kind of scientism as their starting point. Likewise, many progressives adopt an oppressor-oppressed frame as an unquestioned assumption. And many Nietzscheans and existentialists, of both right and left, assume that morality is nothing but a human choice to value this or that, whether they are justified in thinking so or not.

Indeed, many thinkers—secular and religious, left and right—fail even to articulate, let alone to justify, their deepest assumptions.

In other words, presuppositionalists have perfectly diagnosed the problem.

But their prescription is wildly incorrect.

Having diagnosed most human beliefs as resting upon unjustified presuppositions, presuppositionalists then prescribe that we also rest our beliefs upon unjustified presuppositions. The solution to the problem of unjustified presuppositions is, apparently, to adopt and to assert our own unjustified presuppositions.

But this is to prescribe as the antidote a heavy dose of the disease.

A postmodern perspectivalism results. Rather than justifying or interrogating our presuppositions, discourse devolves into the power to assert rather than argue for our preferred perspective. Truth is lost in the mix.

At the foundation of each of these worldviews (what

has recently called “internally-consistent systems”) remains the unanswered (even unasked) question, “But are these presuppositions true?”Each perspective boasts of its coherence and of its conclusions’ following rationally from its preferred starting assumptions.

But do its tenets and assumptions correspond to reality? Or are they contradicted by reality?

Some will respond that correspondence is a naïve idea for these who haven’t seen the postmodern light. I simply ask them to tell me with a straight face that asking whether our unjustified beliefs are true is an unnecessary question.

Presuppositionalism has diagnosed the problem.

But what it offers is the opposite of a solution.

What, then, is the solution to the presuppositional predicament?

The solution to the problem that many people’s worldview rests upon unjustified and sometimes unarticulated assumptions is

to articulate and interrogate those assumptions.

Presuppositionalists, in fact, allow for a kind of interrogation of presuppositions, which they call “transcendental argumentation.”

Transcendental argumentation test whether a given worldview can be maintained consistently and practically, or whether its beliefs are unlivable, self-contradictory, and self-undermining.

But since several hundred years before Christ, this same kind of investigation has been performed under another name…

Now, if presuppositions like “Nature has no moral valence,” “Only what science discovers is true,” and “There is no truth, only power,” were the starting points of thought, there would be no propositions or considerations prior to them. There would be nothing against which one could test them. There would be no grounds upon which one could build an argument for or against them.

Admittedly, opposing worldviews would possess arguments against each other, beginning from their own presuppositions. For example, the Christian could oppose scientism, saying, “Only what is revealed in Scripture is certainly true; therefore, it is false that only what science discovers is true.”

But scientism could oppose Christianity, saying, “Only what science discovers is true; therefore, it is false that Scriptural revelation is a certain source of truth.”

And there would be no way to decide between these contradictory presuppositions.

Likewise, if people inevitably began their thinking from unjustified propositions, like those above, then you would expect that there wouldn’t exist a human discourse concerned to interrogate and consider arguments for and against such propositions.

But there is such a discourse.

There does exist a human discourse concerned to interrogate and consider arguments for and against the propositions upon which most people’s beliefs rest. It’s called…

philosophy.

Philosophy is the human practice of examining those of our beliefs that appear to be most fundamental.

Now not everyone puts much stock in philosophy. Can philosophy really go head-to-head, for instance, with science? Can a philosopher convict a scientist of introducing unjustified metaphysical presuppositions?

Here’s an example of a philosopher doing just that.

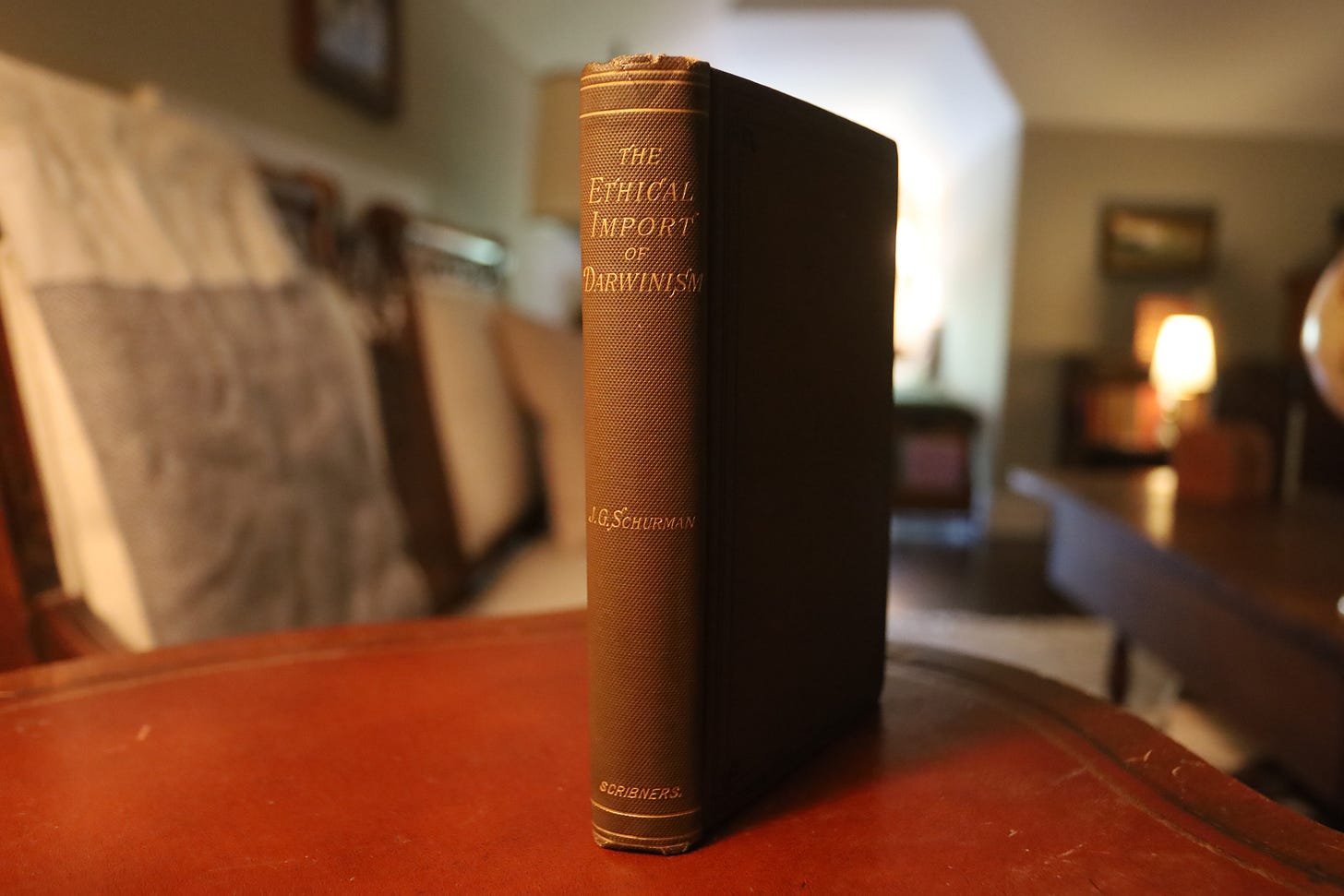

Example 1: Darwinism and Metaphysical Naturalism

In The Ethical Import of Darwinism (1887), Cornell philosophy professor-cum-university president Jacob Gould Schurman convicted Darwinists of presupposing materialistic philosophy, rather than following the science.

Schurman’s lasting contribution is his observation that Darwin’s theory of natural selection explains the survival, but not the arrival of the fittest. “The Arrival of the Fittest” was the name of a 2014 book by a contemporary evolutionary biologist Andreas Wagner that challenged the Neo-Darwinian orthodoxy that the variations of which natural selection works are random, rather than determined by the intrinsic nature of the organism.

“Natural selection may explain the survival of the fittest, but it cannot explain the arrival of the fittest.”

Hugo de Vries, Species and Varieties, Their Origin by Mutation, unknowingly paraphrasing Jacob Gould Schurman1

And indeed, the first place Schurman exposes unjustified assumptions is in the scientific content of Darwinism. In his third chapter, “The Philosophical Interpretation of the Darwinian Hypothesis,” he argues that many Darwinists assume that Darwin explained much more than he in fact does.

Darwin’s natural selection, Schurman notes, explains the culling of less fit variations. But it does not explain whence the variations in organisms arise. Nor does it explain where the organisms themselves came from in the first place! To quote him:

“Here everything is assumed with the primitive organisms and their innate tendency to vary.”

—Jacob Gould Schurman, “Chapter III. The Philosophical Interpretation of the Darwinian Hypothesis,” The Ethical Import of Darwinism, p. 94

However, because of their prior metaphysical opposition to supernatural causality, often rooted in the conflation of methodological with metaphysical naturalism, many Darwinists jump to the conclusion that Darwin explains all. But Schurman advises:

“If this analysis of the fundamental conceptions of the Darwinian theory be correct, much less is really explained by that theory than its advocates have been in the habit of supposing.”

—Schurman, The Ethical Import of Darwinism, p. 94

Darwinists scientific and metaphysical assumptions are also rooted in a lack of historical perspective. Many late nineteenth-century Darwinists thought that the theory of evolution was a new theory, recently proven by the best of natural science.

But Schurman raises historical evidence against this proposition. Namely, the purposeless evolution of organisms, filtered by survival, is a theory that appeared in ancient, pre-Socratic atomistic (i.e., materialistic) philosophers:

“[The] doctrine of fortuitous combinations is not the outcome of modern evolutionary science, but the undemonstrated postulate of every merely mechanical philosophy. It is as old, therefore, as materialism; and the Greek atomists expounded it as skillfully as the modern English biologists.”

——Schurman, The Ethical Import of Darwinism, pp. 101-102 (emphasis added)

The metaphysical doctrine that biological organization can be attributed to chance (“the doctrine of fortuitous combinations”) is not a deliverance of science; it is an undemonstrated postulate, an unjustified presupposition, of an age-old materialistic philosophy.

Furthermore, this materialistic theory was opposed by philosophers of a more mentalistic (mind more fundamental than matter) and teleological (purpose is real) orientation, like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. And the argument between ancient atomists and ancient teleologists was carried out on philosophical grounds.

But if evolution by natural selection was articulated by ancient philosophers, then it is not a novel theory, nor obviously a purely scientific one.

Likewise, if the merits of non-teleological and teleological explanations in biology have been debated for millennia on grounds other than the latest science—and the latest arguments bear a striking resemblance to those earlier philosophical arguments—then it is no longer clear that the argument for non-teleological evolution is a scientific one. It may be but the latest swing in the metaphysical pendulum between materialist metaphysics and teleological metaphysics.

In my Aristotle’s Argument Against Evolution, I quoted the ancient materialist Empedocles’ poetic statement of natural selection. For now, here’s Aristotle’s summary of Empedocles:

“Wherever then all the parts came about just what they would have been if they had come to be for an end, such things survived, being organized spontaneously in a fitting way; whereas those which grew otherwise perished and continue to perish, as Empedocles says his ‘man-faced ox-progeny’ did.”

—Aristotle, Physics, II.8 198b 29-33)

Schurman also carefully distinguishes science from metaphysics. On the one hand, we have the historical-scientific thesis of common descent by successive modification, involving natural selection as one cause; on the other, the metaphysical thesis that the causation and explanation of such modification is purposeless and ruled only by the principle of natural selection.

The former scientific theory does not entail the latter metaphysical thesis.

(In fact, Schurman accepts as science the doctrine of common descent by successive modifications. He is, in his conclusions, a theistic evolutionist.)

Referring to common descent and natural selection, Schurman says:

“This is the essential content of Darwinism.

“And it is manifestly consistent with any philosophy, empirical or rational, spiritualistic or materialistic, theistic or atheistic.”

—Schurman, The Ethical Import of Darwinism, p. 97

Schurman believes that Darwin has presented ample evidence of common descent or certainly novel scientific evidence of common descent by successive modification.

But that this scientific thesis implies or is identical to the metaphysical thesis is a logical and philosophical error:

“[There] can be no doubt about the fact that most of the evolutionists have identified the doctrine with a philosophy of mechanism and fortuity.

“But neither Darwinism nor evolutionism in general really necessitates, or even warrants, such a speculative inference.”

Above, Schurman identified the Darwinist’s error as that of assuming an undemonstrated postulate. Here he identifies their error as a fallacious inference. The inference is that the scientific thesis of Darwinism (or evolutionism in general) logically implies or entails materialistic philosophy.

While materialism (or “the doctrine of fortuitous combinations”) is taken to be the logical conclusion of Darwin’s scientific theory, it turns out that materialism has been assumed in interpreting Darwin’s scientific theory as a general, chance-based metaphysical theory of everything.

Metaphysical Darwinists presuppose “the doctrine of fortuitous combinations” in their interpretation of Darwinian science; they then infer from what they perceive to be the Darwinian science the truth of “the doctrine of fortuitous combinations.” They presupposed their conclusion. And thus, their grounds for holding that conclusion evaporate.

Schurman, a college philosophy professor and university administrator, has demonstrated that many scientists and philosophers rest their Darwinian worldview on unjustified presuppositions.

But how did Schurman do it? How did a philosophy prof challenge the fundamental presuppositions of eminent scientists? On what grounds was he able to test metaphysical presuppositions for their truth or falsehood?

First, Schurman appeals to science itself.

Schurman’s first argument, with continued relevance to evolutionary biology, is a scientific one for the limits of Darwinian explanation. Natural selection, he argues, is but a destructive process. It requires the existence of organisms and the production of variations of those organisms in order even to get started.

In his writing, Darwin always assumes that these variations will be indefinite (Schurman, 81-82); but his contemporaries’ and today’s biology suggest that variations are likely to be definite, flowing from the nature of the organism.2

With this chastened view of what natural selection is, we are much less likely to conflate natural selection with a general “doctrine of fortuitous combination.”

Second, Schurman appeals to history.

He offers evidence from the history of philosophy and science that the explanation of apparent design as chance combination is an ancient tenet of materialistic metaphysics and not a unique deliverance of modern science. Such contextual examination calls into question the stamp of “science” that naturalistic metaphysics tries to wear.

Third, using a particular kind of human understanding, Schurman draws our attention to the differences between the disciplines of science and philosophy.

For instance, he notes that purely scientific theses are compatible with multiple metaphysical interpretations. Thus, if Darwinism is taken to be an incipiently atheistic thesis then the thesis we have in view is not scientific but metaphysical. Schurman notes that metaphor and even capital letters—“a title so suggestive of volitional attributes as ‘Natural Selection’”—can lead us to jump from purely scientific to metaphysical conclusions.

The sentence in which he makes that claim is long, but so enjoyable (italics added; and find an audio recording of me reading it below):

“But when the designation for a purely natural process has, through the suggestions of metaphor and the use of capital letters, come to stand for something more than a process, and, from constant association with an extraneous metaphysics, has acquired the potency of a conjurer’s formula in the philosophy of life, mind, and conscience, it is high time to set about the perennial problem of laying the dust raised by dogmatic metaphysicians, who are all the more insidious when they disown their vocation and come to us in the name of positive science with the prestige that science gives.”

—Schurman, The Ethical Import of Darwinism, pp. 83-84

Fourth and finally, Schurman engages in, simply, philosophical reasoning.

Aristotle’s reasoning concerning chance and purpose (in Physics, Book II) is a paradigmatic example of philosophical reasoning concerning nature, one which Schurman’s reasoning parallels.

Aristotle argued that, in human discourse, we attribute something to chance when two things, each of which have some purpose, converge in a way that is not the purpose of either. Thus, if I walk to the marketplace to purchase figs and you to purchase cheese, our bumping into each other is something we attribute to chance, though not because either of us was moving purposelessly, but because our meeting was not either of our purpose. But chance explanations presuppose purposeful movement.

In the same way, Schurman argues that chance-based explanations assume something prior that is not attributable to chance. So, Schurman admits that natural selection operates by chance. But he argues that these chance operations assume organisms and their variations, which cannot themselves simply be chalked up to chance.

In such reasoning, both Aristotle and Schurman operate by attending to the role certain kinds of explanation play in human discourse. In other words, Aristotle and Schurman attend to the very nature of such things as chance, necessity, and purpose which ordinary people and scientists commonly assume.

As Schurman articulates it,

“That [task] falls to philosophy, whose function it is to examine the starting-points and first principles with which the various sciences uncritically set about their specific task.”

—Schurman, The Ethical Import of Darwinism, p. 78

Attention to the categories of human thought and discourse is not the general method of science, but of philosophy. Schurman attends to the nature of human discourse, noticing the difference between scientific discourse and theses and metaphysical discourse and theses. By a lack of such attention, scientific atheists commonly conflate the one with the other.

So, what is prior to metaphysical presuppositions? On what grounds can philosophers challenge the apparently fundamental beliefs of both ideologues and scientists?

The philosopher appeals to things as various as science, history, human understanding, and philosophical reasoning, with its attention to the nature of human discourse.

If presuppositions were truly foundational, or if we all perceived evidence only through our presuppositions, it would be impossible to challenge presuppositions from such sources.

But it is not impossible.

Jacob Gould Schurman just did it.

(And, by the way, he did it without assuming Christian, or even theistic presuppositions.)

“Where science ends philosophy begins. The one is concerned with the discovery of processes, the other has to analyze the ultimates—realities or conceptions, being or thought—which the processes everywhere involve.”

—Schurman, The Ethical Import of Darwinism, 76

The Presuppositions of Analytic Philosophers

But that brings me to my dissertation.

In my dissertation, I aim to unearth and interrogate some of the unexamined presuppositions of swaths of analytic philosophers.

The question is whether I, like Schurman, can interrogate purportedly fundamental presuppositions through means including philosophical reasoning, without assuming unjustified presuppositions (“undemonstrated postulates”) of my own.

While I believe that philosophy, and particularly analytic philosophy, has the tools to interrogate presuppositions, it is nevertheless true that many philosophers operate on unarticulated and unjustified presuppositions. Again, the presuppositionalist diagnosis is spot-on.

I recently encountered an example in the contemporary analytic philosophy I am studying for my dissertation.

Example 2: The Millian Presupposition of Kripke’s Epistemological Argument Against Millianism

The arguments of Saul Kripke (1940-2022) play an important role in my thesis. Kripke argued against descriptive theories of reference in his influential Naming and Necessity.

(I went into this in my article about whether having false beliefs about God means you worship a different God.)

Previously, I took Kripke’s conclusions for granted and assumed that his arguments were sound, without being too clear on what exactly those arguments were. In fact, I made some of Kripke’s arguments myself in the above article.

But in recent months, I’ve been trying to achieve clarity about his arguments and to figure out just how much they proved.

In the process, I have come to see the limits of his arguments, including that one of his arguments, the epistemological argument, presupposes the truth of the thesis he meant to prove: Millianism about proper names.

Named after its proponent, John Stuart Mill, Millianism about proper names is the (sensible) idea that proper names do not have a descriptive meaning but mean their referent, directly. John Stuart Mill argued, for instance, that Dartmouth refers to a certain British city and would continue to do so even if the river Dart shifted so that its mouth was no longer at Dartmouth.

Similarly, even for Native Americans, if young Crazy Horse grows up to be sober and self-controlled, he is still rightly called “Crazy Horse”; “Crazy Horse” continues to refer to him.

Millianism is opposed to descriptivism about proper names, the view that proper names refer to individuals in virtue of a descriptive meaning in our heads that the individual satisfies. (For more on descriptivism, see the section of the above article titled, “What Is Descriptivism?”.)

One of Kripke’s arguments for Millianism is called “the epistemological argument,” and it is an argument from the nature of our a priori knowledge about individuals.

The epistemological argument goes like this:

If the descriptive theory of names were true, then you would be able to know a priori that Crazy Horse is neither sober nor self-controlled.

But we cannot know this a priori, since a posteriori observation may reveal that Crazy Horse is both sober and self-controlled.

Therefore, descriptivism is false, and Millianism true.

In fact, this was the first argument I made in the above article.

But as it turns out, Kripke’s epistemological argument depends on an “undemonstrated postulate,” unfortunately, the undemonstrated postulate of the Millian theory of names.

Consider premise 2 of the argument. In the latter half of the sentence, we read “a posteriori observation may reveal that Crazy Horse is both sober and self-controlled.”

But, if the descriptive theory of names is true, then that sober-minded, indigenous person is not, therefore, Crazy Horse. If “Crazy Horse” refers in virtue of locating an individual who matches its descriptive meaning, then the individual formerly known as “Crazy Horse” is not and never was actually Crazy Horse.

In other words, the middle premise of Kripke’s epistemological argument makes a Millian use of the proper name “Crazy Horse.” Hence, it depends for its justification on Millianism about proper names, the very thesis we were aiming to prove.3 Until we can justify that theory, we are not entitled to assume that our uses of proper names refer directly.

So Kripke’s (and my) epistemological argument fails, by presupposing the thesis it sets out to prove.4

As philosopher Robin Jeshion puts it:

“The direct reference theorist regards the [relevant] premise as evident only because of an antecedent commitment to his preferred semantics.”

—Robin Jeshion, “The Epistemological Argument Against Descriptivism,” p. 341

Now I think that Millianism is true. In fact, in my dissertation I want to concur with so-called meaning externalists, direct reference theorists, and Russellians that something similar applies to almost all of language. All language refers beyond itself, to something that transcends the provisional conceptual descriptions in our minds.

But I need to argue for this thesis in ways that do not, like the epistemological argument, presuppose what they set out to prove.

Rather, like Jacob Gould Schurman, I need to call on all the resources available to me as a philosopher, from philosophical reasoning itself and careful linguistic analysis to scientific and empirical observation, to argue for my philosophical conclusions on independent grounds.

As I articulate and challenge the undemonstrated postulates of other philosophers, I can and must do so without simply appealing to undemonstrated postulates of my own.

This is the work of philosophy. And it is really nothing more than 1) asking what is true and 2) finding and spelling out the considerations that bear on that all-important question.

The Necessity of Philosophy

The work of philosophy is not optional.

If you base your life upon presuppositions you have not examined, then, whatever your ideological commitments, life can throw a wrench in your internally-consistent system.

For example, if your fundamental presupposition is that wealth arises by theft of the oppressed by their oppressors, then acquaintance with a single morally-upstanding and likable business-owner could undermine your entire worldview.

Alternatively, if your fundamental assumption is that biblical statements are the only premises from which certain conclusions can be drawn, then deep and unexpected suffering that causes you to question whether the Bible’s statements are true, e.g., “for those who love God all things work together for good,” (Rom 8:28), then that has the potential to shake the entire edifice of your belief.

Or, if your fundamental assumption is that religious people believe from ignorance, then acquaintance with just one believing philosophy professor could undermine the basis of your non-belief.

To me, the most exciting stories in the world are those where just such underminings occur. These events prove that reality can break in past the wall of our presuppositions, and frequently does. Everyone, and not just Neo-cons, is capable of being “mugged by reality.”

That is why I think it is untenable for us to accept the state of affairs as presuppositionalists find it. The intellectually responsible thing cannot be to remain in our bubbles of belief, trying to maintain the integrity of a sphere built from soapy water, just waiting for reality to pop them.

In both the examples we considered, the presuppositionalist diagnosis proved correct. Metaphysical Darwinists presuppose as an undemonstrated postulate the doctrine of fortuitous combination, as Schurman calls it. Kripke and other advocates of the epistemological argument against descriptivism tacitly presupposed the very semantic theory they set out to prove.

But the solution is not to acquiesce in the presuppositional predicament. We can’t just “plump” for our preferred set of presuppositions. We have to test the undemonstrated postulates of our and others’ worldviews. And that testing, which presuppositionalists acknowledge as “transcendental argumentation,” has, throughout human history, gone by the name of philosophy.

The solution to the presuppositional predicament is the practice of philosophy.

The intellectual task of a human being is not to shore up our preconceptions, but to have our thinking formed more and more by how things are.

And philosophy, I believe, can help.

Wagner quotes Hugo De Vries as the source of the “arrival of the fittest” quotation, but De Vries in turn attributes it to a book review by Arthur Harris. Harris expresses ignorance of the quotation’s source. That source is Schurman’s The Ethical Import of Darwinism, as I learned from this article. “Whoops,” the Darwinists say, “we quoted a Christian philosopher!”

Both Wagner, in Arrival of the Fittest, and philosopher Jerry Fodor in What Darwin Got Wrong (2010) argue this cogently, with reference to the best of recent evolutionary biology. Though Fodor notes (and coauthor Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini) that many non-specialists and practitioners of evolutionary spin-off fields continue to assume that Neo-Darwinism, relying only on environmental sources of change and indefinite, random variation, explains the evolution of species.

See Robin Jeshion’s paper, “The Epistemological Argument Against Descriptivism,” for the source of this argument, on pages 340-341, available for free here.

Actually, even this counter-argument fails to unearth all of the necessary presuppositions. For instance, if a proper name has a meaning, does it refer in virtue of the individual satisfying the description? This would not be the case if, for instance, Crazy Horse could fail to live up to the meaning of his name, will remaining the referent of “Crazy Horse.”

Also, I’m not sure that using the name “Crazy Horse” to refer to Crazy Horse does amount to assuming the Millian theory of names. The Wittgensteinian possibility is that this is ordinary-language evidence that people do not operate by the descriptive theory of names. All such possibilities must be considered and weighed in a responsible and thorough philosophical argument

Presuppositionalism is the cauterized wound where Evangelicals amputated philosophy. It is an entirely defensive apparatus to keep out infection and provide a simulacrum of the epidermis for that body. You should not consider it a conversation partner or interlocutor, at least in the traditional sense, because it does not share interest in understanding the world. It isn't an alternative philosophy so much as the explanation of why philosophy is unnecessary, unhelpful, or perilous, even if some of the bolder proponents take a dip in the moat from time to time out of boredom.

--

To me, the bigger question is that of the "Christian philosopher". There are two ways that this may be parsed:

1. That a philosopher may be Christian. To put it another way, that a philosopher may come to Christian conclusions without ceasing to be a philosopher. Or, to rephrase, that Christian conclusions are--at least theoretically--philosophically valid.

2. That there is a way of doing philosophy--a philosophically valid way--that is uniquely Christian. This might take several forms, but a common one would be as a vantage, starting, or given point from which the subject engages with the objects of philosophy. Or, it could be viewed as a sort of calibration of which sorts of philosophical questions one asks and answers--"if this is so" or "assuming that such and so is valid and/or sound" may be perfectly reasonable places to begin if one does not wish to litigate first things for one's whole career or life.

--

A third way does exist, which is to assume that philosophy is either a euphemism for Satan's alternative theology or that it is synonymous with theology. Presuppositionalism seems to ride a little toy train along tracks built at the top of the fence between the second and third position, but it really is this third position, at root. I would suggest that you say as much and begin engaging with the first two groups of people.

--

Which is not to say that you shouldn't write on the subject or continue to speak to Presuppositionalists, just that you should do so knowing that they don't have any interest or intent in doing philosophy and that they may well be willing to debate or argue about it--to keep up apologetic street cred, if nothing else--but will be either bad faith actors or so deceived about what they are doing that they behave like Pharisees. Don't throw peals before swine, lest they attack you and trample the pearls.

--

LOVE LOVE LOVE having the ability to listen to this while doing the dishes. I cannot express how valuable the feature is to me and how sufficient the British robot voice is--apart from turning Kripke into a Crip like Snoop Dogg.

This is a really interesting read, and much of it is over my head! Thanks for writing!

As per the claim that Presuppositionalism doesn’t have the proper prescription to the problem, I think it’s important to consider that in Van Til’s book Defense of the Faith he wasn’t calling for us to examine presuppositions like “Nature has no moral valence,” “Only what science discovers is true,” and “There is no truth, only power.” The entire book is structured by examining metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics. Instead of “There is no truth, only power,” Van Till says to examine the philosophical first principles presupposed behind it. In my reading of Van Til he’s not nearly as separated from Philosophy as you make him appear in this.

To me it seems that presups, according to Van Til, have both the right diagnosis and the same solution you do: philosophical presuppositions.

I am not getting a PhD so I know I’m probably wrong somewhere I here, what am I missing?