In my upcoming course, I will guide students along an intellectual path From Theology Nerd to Christian Humanist.

It may come as a surprise, then, that the course’s syllabus features prominently the discipline of analytic philosophy.

To view the course syllabus of From Theology Nerd to Christian Humanist, click here:

How can the domain of logic-choppers and scientific reductionists be a site of humanism, Christian or otherwise?

By the lights of many, analytic philosophy is among the most inhumane of the disciplines.

As has been said:

Continental philosophers produce these incredibly interesting questions but murky and, in effect, unintelligible answers; whereas the analytical philosophers produce these wonderful, lucid answers to . . . completely pointless questions.

— Roger Scruton, quoting Derek Parfit

Yet I believe that, in certain corners of the analytic discipline, humane philosophy is to be found.

This reading guide will direct you to those corners.

I. Towards a Humane Philosophy: Roger Scruton

The challenge to analytic philosophy has been best expressed by the late Sir Roger Scruton, in his 2014 address “Towards a Humane Philosophy,” at the Alpine Fellowship:

In his lecture, to which I urge you to listen in its entirety, Scruton challenged contemporary analytic and continental philosophy to cease the work of scientific reductionism and postmodern deconstruction.

Instead, he urges philosopher to be in the business of “reweaving the torn Lebenswelt.”

(The Lebenswelt is the shared “life-world” that is debunked by scientific reductionism and deconstructed by postmodernism.)

To get a start in humane philosophy, one can do no better than to begin with the work of the late Sir Roger Scruton.

Beauty

Aesthetics is central to Scruton’s philosophy. Scruton argues for relatively traditional notions of beauty against modernism and deconstructionism. He also defends the place of beauty in common life, arguing that finding and creating beauty is how human beings make themselves at home in the world.

See also his documentary, Why Beauty Matters (2009):

Sexual Desire: A Philosophical Investigation

Scruton gives a deeply humane exploration of sexual desire. He argues that sexual desire is not the desire for sex, but a desire for another person. From this, ethical implications follow. For a summary, watch his lecture, “Sexual Morality for Heathens.”

The Meaning of Conservatism

Scruton spells out a conservative political philosophy, deeply engaged with philosophy, history, and law.

Kant: A Very Short Introduction

This volume articulates a compelling reading of Kant, foundational for Scruton’s own philosophy. Kant articulates a way to believe in what it is to be human in relation to the scientific conception of the world.

On Human Nature

Scruton’s compelling riposte to modern naturalism. Scruton argues that human life is indelibly characterized by a first-person perspective and moral and aesthetic concerns which cannot be reduced to the physical dimension of existence.

Other works include Scruton’s reflections on religion, such as his Gifford Lectures, The Face of God, and The Soul of the World. Scruton ended his life a church-goer, organist at his local parish, and perhaps, to some extent, a Christian.

And Conversations with Roger Scruton presents the story of Scruton’s life and philosophy through interviews with him.

But the work of Sir Roger Scruton is not the only place to find humane analytic philosophy.

II. The University of Chicago’s Humane Philosophy

At the University of Chicago, I encountered a school of philosophy that aspired to engage not merely in the blinkered, contemporary scientistic discipline, but in the perennial tradition of philosophy.

Appealing to Aristotle, Aquinas, Kant, and Hegel, philosophers at U of Chicago attempted to do contemporary philosophy but rooted in the history philosophy, and bridging the analytic-continental divide.

(I wrote about UChicago’s approach in “Non-Dogmatic Philosophy at the University of Chicago.”)

If I could summarize and simplify, Chicago philosophy was critical of naturalism on the ground of its inhumanity. In virtue of being human, we are all apprised of a perspective on the world other than the scientific one. Without any discredit to the scientific picture, philosophy can explore and elucidate the content of the manifest image and the first-person perspective.

From UChicago, this school of philosophy extended from Chicago to Pittsburgh (and from there, to Leipzig), and the professors at these three universities have composed much of its recent philosophical canon.

Here are some of articles and books at the core of that canon.

“Additive Theories of Rationality: A Critique,” Matthew Boyle

From Thomism and Aristotelianism, we gain the thesis that man is a rational animal. This is often denied in naturalistic philosophy, as continuity between man and the other animals is maintained. Not so at U of C, which defends rationality as the mark of humanity.

However, there are philosophical differences over how to understand human rationality. Many accounts of human rationality, both Thomistic and liberal, maintain that rationality consists in having something added on top of our animal capacities. Boyle challenges the idea that our being rational transforms our “lower” capacities of sense and desire. The result is the hallmark of U of Chicago philosophy and its convergence with German Idealism: A transformative account of human rationality.

“The Representation of Life,” Michael Thompson

There are at least two strands within the Chicago school, which stand in some tension: A Kantian and a Neo-Aristotelian one. Boyle represents the former, Thompson the latter. Thompson argues for a Neo-Aristotelian philosophy of nature in this article without being a Thomist or an antiquarian. He introduces a philosophy of nature that diverges from contemporary naturalistic philosophy, includes formal and final causation in its way, but all in contemporary analytic idiom.

Thompson’s motive for reviving Aristotelianism is to found a virtue ethics on a robust conception of nature, bypassing the Is-Ought divide. The ethics of Philippa Foot, Thompson’s teacher, would be the result — though there is close connection to contemporary Old Natural Law theorists and contemporary Nietzschean vitalism.

“Two Sorts of Naturalism,” John McDowell

In Kantian fashion, McDowell opposes the Neo-Aristotelian attempt of Thompson and Foot to found ethics on an expanded, Aristotelian notion of nature. (By implication, Old Natural Law theorists and vitalists are all implicated.) Beginning with the fable of the rational wolf, McDowell shows that ethics cannot be founded on what is given in nature, since rationality introduces the possibility of questioning what is given.

McDowell argues that ethics must introduce considerations that speak to reason, rather than merely appealing to our nature. We as rational beings must appreciate these in virtue of gaining a second nature, as Aristotle described habituation. What follows is not ethical supernaturalism, but a less restrictive, more liberal form of naturalism. This argument is the foundation of McDowell’s Mind and World.

“What Is It to Wrong Someone? A Puzzle About Justice,” Michael Thompson

This article by Thompson is more Hegelian than Aristotelian in flavor. Thompson argues that relations of justice between people require that they are appealing to the same moral standards, rather than different ones, even if they happen to converge. This aligns with Hegel’s critique of Kant, that it is not enough for people to intuit the categorical imperative; they must be related in a state that apprises them of a particular social standard of justice. Thompson will take this in a Neo-Aristotelian direction in other articles, but as more of a Kantian-Hegelian, this article is highly compelling.

Mind and World, John McDowell

McDowell’s Mind and World is the heart of the U of Chicago Kantian tradition. In it, McDowell argues that a satisfactory account of our knowledge of the world requires that human rationality is not reductively naturalistic. Humans participate not only in the space of causation in accord with natural law, but of relations of rational justification, the space of reasons.

All the while, McDowell maintains that we remain natural beings. We participate in the space of reasons by the acquisition of a second nature and by inculcation into a social tradition. In this, McDowell picks up Aristotelian and Hegelian themes, bridging the analytic and continental traditions, while challenging contemporary “bald” naturalism, with his liberal naturalism.

“Why Kant Is Not a Kantian,” James Conant

The Kant I was presented with at the U of Chicago is not the Kant of almost all contemporary philosophy: The one who proposes that we are blinkered by our categories of experience. At U of C, Kant was a realist, and one who hearkened back to Aristotle and the scholastic tradition.

In “Why Kant Is Not a Kantian,” Conant proposes this reading of Kant, arguing that the categories are supposed to be what makes objective experience possible, not impositions on experience that prevent us from encountering the real. Conant argues that why our contemporaries call “Kantianism” was one of Kant’s main objects of critique. If the categories are imposed on experience by us, or even by God, this is “to give the skeptic what he most desires.” Kant was not an arch-skeptic à la Descartes or Hume, but an opponent of such skepticism, seeking to bring us back to knowledge of objects through the unified working of reason and sense, which modern philosophy had divided.

By the way, for some background, Conant, McDowell, and their late colleague John Haugeland conducted a reading group of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason in the 90s at Pitt. During it, they came upon this alternative reading of Kant, which influenced the work of each.

“The Search for Logically Alien Thought,” James Conant

In this article, Conant introduces another strand of U of C thought, the Wittgensteinian one, which he argues aligns with the Kantian one. Conant begins with the relationship between God and logic. The medievals and moderns tried to honor God by arguing that God could change logic, or at least they were tempted to. They struggled to articulate the necessity of logic while maintaining the freedom of God.

Conant argues that exactly the same philosophical dynamic is seen today, except it is science that philosophers try to honor. Even the laws of logic could be changed by updates to empirical science, Quine and others argued. Conant shows how Kant and Wittgenstein represented a way of thinking about logic as a one-sided limit, the very boundary or form of thought, but one which you could not get outside. This essay would provide the basis for Conant’s recent work The Logical Alien.

“The Province of Human Agency,” Anton Ford

The work of Elizabeth Anscombe on action was prominent at U of C. Anscombe was a kind of Christian Wittgensteinian but, importantly, one who is read by believers and non-believers alike.

Anton Ford is one of U of C’s philosophers of action, who works in the Anscombean tradition. In this article, Ford contrasts an Anscombean way of thinking about human action with the predominant naturalistic variants. Ford argues that we do not merely cause our bodies to move, which then bump into objects, affecting things outside us. Rather, the province of human action extends well beyond the body, engaging human beings with the external world — and calling into quesiton the Cartesian divide between internal and external with which contemporary naturalists continue to operate, despite their antipathy for Cartesian dualism.

Further Reading:

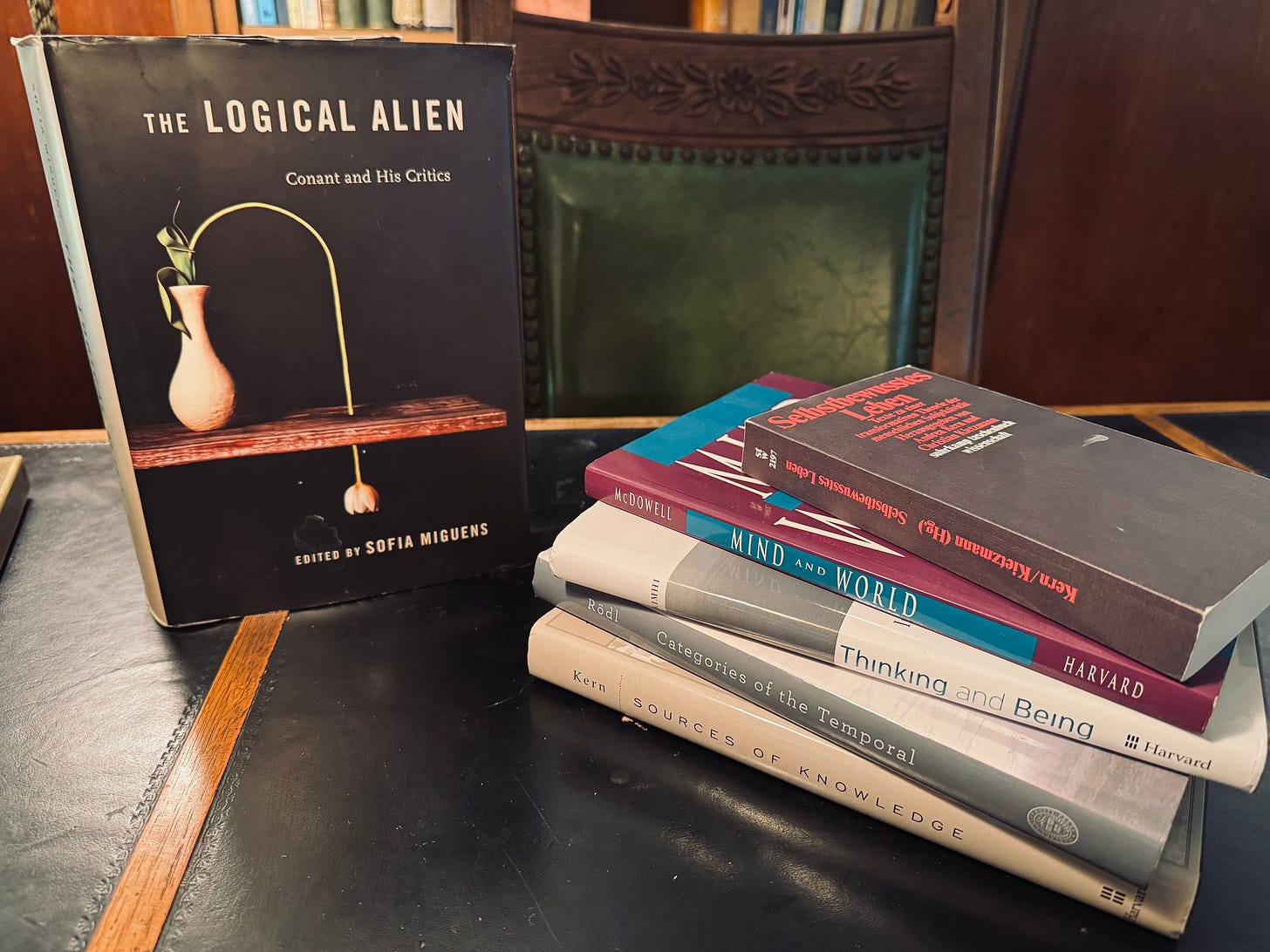

Categories of the Temporal, Sebastian Rödl

(and the other two books of his trilogy)

Rödl is like a German philosophical wizard of the U of C tradition. He is the systematizer and extender of McDowell and Conant’s work, but not for the faint of heart.

just wrote a helpful intro to Rödl on Substack.The Logical Alien: Conant and His Critics, James Conant

Spectacular exploration of the relationship between God, logic, and science. Much of the inspiration for my dissertation comes out of this book.

Intention, Elizabeth Anscombe

Anscombe raises important questions about action that hearken back to scholastic considerations. Readable and influential.

“Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind,” Wilfrid Sellars

I still haven’t read through this. But Sellars is foundational for McDowell. As Conant would say, Sellars represented the Kantian strand of analytic philosophy when it was dominanted by non-Kantians and logical positivists. Sellars argues that a purely causal and reductively naturalistic account of human knowledge will not do.

Contemporary philosophers divide into right Sellarsians (Daniel Dennett — yes, that Daniel Dennett — Ruth Millikan, and the Churchlands) and left Sellarsians (Rorty, McDowell, Brandom).

(Though my dissertation exploits a commonality between Millikan and McDowell, over realism and disjunctivism, crossing the left-right Sellarsian divide.)

Sources of Knowledge, Andrea Kern

Another brilliant German philosopher. Kern addresses the impasses of contemporary epistemology with a McDowellian intervention.

A highlight is the metaphor of shooting basketball free throws for knowing. One can have a capacity to shoot free throws even while shooting 75%. Capacities are fallible without becoming incapacity, and leading to Cartesian skepticism.

“Two Varieties of Skepticism,” James Conant

Conant distinguishes Kantian from Cartesian skepticism. All of contemporary philosophy and pop-culture (The Matrix) is obsessed with Cartesian skepticism. Conant shows a way out without becoming a dogmatic realist. This article explains why I can’t take seriously vast swaths of analytic philosophy. They are enmeshed in the Cartesian problematic, something I now view as rather juvenile.

III. Fathers of Humane Philosophy: Wittgenstein and Strawson

The contemporary Chicago-Pitt school and Roger Scruton share a philosophical heritage. Before their time, humane analytic philosophy was produced by Wittgenstein and Peter Strawson.

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Ludwig Wittgenstein

Looks difficult to read, but start with the propositions numbered 1-7. (Leave the likes of 1.1, 2.1.3, and 6.3.2.1 for later.)

Wittgenstein’s core claims are found at these specific turning-points in the text. In a way that may appear inhumane, Wittgenstein argues for a humane conception of philosophy. He makes space for God and ethics at the boundary of natural science.

On Certainty, Wittgenstein

In the months and weeks before his death, Wittgenstein contemplated whether G. E. Moore was right to think that the world exists. Moore had held up his right hand and argued, “This is a hand. Therefore, the world exists.” Wittgenstein found something queer about the claim to dogmatic certainty about something, which it was odd to imagine doubting. Wittgenstein winds his way between skepticism and common-sense realism in this illuminating document, the last entry of which comes three days before Wittgenstein’s death.

“Freedom and Resentment,” P. F. Strawson

Strawson’s only foray into ethics was his treatment of the problem of free will. Strawson opposed the hard determinists who wanted us to eradicate the practices of praise and blame. He argues that our moral thinking and our emotional reactions are an ineradicable part of being human. They cannot be dislodged by metaphysical reasoning concerning determinism.

However, this also implies that ethics and the moral sentiments are not founded on metaphysics. This essay, assigned at Wheaton by Dr. Mark Talbot, led me to abandon presuppositionalism. Dr. Talbot speculates that it was inspired by Strawson hearing C. S. Lewis’s radio addresses that would become Mere Christianity, given its resonance with MC’s opening argument. (I comment on this in my video rejecting presuppositionalism.)

Analysis and Metaphysics, Strawson

Introduces Strawson’s approach to philosophy as, like Wittgenstein and McDowell’s, therapeutic. We do not need directly to answer the problems of philosophy, but to see our way through them. Reductionism is opposed by a happy acceptance of the scientific image and the manifest image in harmony. No theology results, but no anti-theology either.

Skepticism and Naturalism: Some Varieties, Strawson

Another presentation of Strawson’s unique approach. Strawson argues for a liberal naturalism, the same view McDowell will take up. He opposes several kinds of skepticism and asks us to rest content with our natural human perspective. He identifies scientism or scientific naturalism as a kind of skepticism, one we ought to reject.

“Intellectual Autobiography,” Strawson

Excerpt:

When I asked whether I believe in God, I am obliged to answer ‘No’; I have difficulty with the concept. But I am sometimes tempted to add that I believe in grace—a quality which eludes precise description, but is sometimes manifested in the words and actions of human beings.

“Conversations with Wittgenstein,” M. O’C. Drury

Drury once came to Wittgenstein desiring to become an Anglican priest. Wittgenstein dissuaded him, persuading him to be a doctor. Yet many philosophical and religious themes are discussed in their conversations which Wittgenstein does not discuss explicitly in his writings. These read like the reminiscences of one of Christ’s disciples.

IV. Philosophy with the Fellow Travelers

In my article, “From Theology Nerd to Christian Humanist,” I highlighted the joys of discovering the “fellow traveler”: The fellow traveler is one who, by his own lights, has stumbled upon a preamble of faith.

In analytic philosophy, the preamble of faith is usually the limits of the naturalistic worldview. However, the fellow traveler discovers this without Christian presuppositions or religious motivations. Often, he avoids drawing metaphysical conclusions — as Strawson and McDowell both adopt a liberal naturalism, one that makes space for humanity, rather than any kind of dualism or supernaturalism.

In the process of learning from the fellow traveler, we learn why we believe what we believe.

Also, many of our arguments and thoughts are corrected or moderated. Learning from Scruton and the UChicago school of thought has led me to abandon many apologetics-style arguments. Many arguments for dualism and theism attempt to prove too much.

Finally, we gain the ability to engage on common ground, rather than forcing the “antithesis.” If John McDowell and Peter Strawson, secular analytic philosophers, can argue for the limits of naturalism, then I can too without forcing the antithesis between naturalistic and theistic worldviews.

In the process, we become capable of thinking and arguing in ways that are compelling to our fellow man and, in fact, of becoming human again ourselves.

In my experience, analytic philosophy, properly curated, can be a great path for the theology nerd to become a Christian humanist.

Free Syllabus and Course Signup

If you appreciate learning about other disciplines to broaden your perspective, click this link to receive the syllabus for my upcoming course, From Theology Nerd to Christian Humanist:

By signing up, you’ll also receive further information about the course and the invitation to enroll. My current plan is to run the six-week course in July and August this summer, but sign up to get the details over the next couple of weeks.

For more on the subject, read the foundational article of the course:

From Theology Nerd to Christian Humanist

Dear reader, in this post, I introduce the theme of my upcoming course, “From Theology Nerd to Christian Humanist,” a six-week foray into the limits of theology and the breadth of human experience.

Thanks for all this. Good content. I am away from this world and need to do the reading. Please keep posting stuff like this.