Christian Naturalism: A Theological Hypothesis

What if even man's final end is proportionate to his nature?

It has long been my aspiration to develop a Protestant theology of nature and grace.

In Catholic theology, nature and grace is a locus, or topic of the discipline. In Protestant theology, it has more often been addressed implicitly or occasionally. Dutch Neo-Calvinism was an account of nature and grace; American Reformed debates concerning grace and merit before the fall, pitting Westminster West against the Federal Vision, addressed the theology of nature and grace; and ongoing debates about the place of natural theology and natural law in Protestant thought are a contribution to the same.

But can the topic be treated more systematically? And what account of nature and grace would result from the line of thought I have pursued in my studies this last decade, and in my writing at The Natural Theologian these two years?

In this essay, I sketch out a new theological hypothesis with regard to nature and grace: Christian naturalism.1 The proposal is that:

Grace restores and perfects nature but does not elevate us beyond our nature (as Dr. Feingold argued in our interview).

There is no grace before the fall.

Man’s final end will be proportionate to our nature and encompass resurrected, physical flourishing.

We will not “behold God through his essence”; we will increase ad infinitum in knowledge of God in accordance with our finite mode of cognition.

While the topic is very meaty, this article merely sketches the outlines of such a view. Feel free to simply scroll to the sections that interest you and get a sense of what I am proposing.

After discussing the polemical background for this discussion, I’ll address the following theological topics:

No Grace Before the Fall

No Covenant of Works

Grace: Not Metaphysical, But Moral

Christ’s Human Nature: Like Ours in Every Way

Felix Culpa and Human Maturity

Man’s Final End: Proportionate to Our Nature

Polemical Background

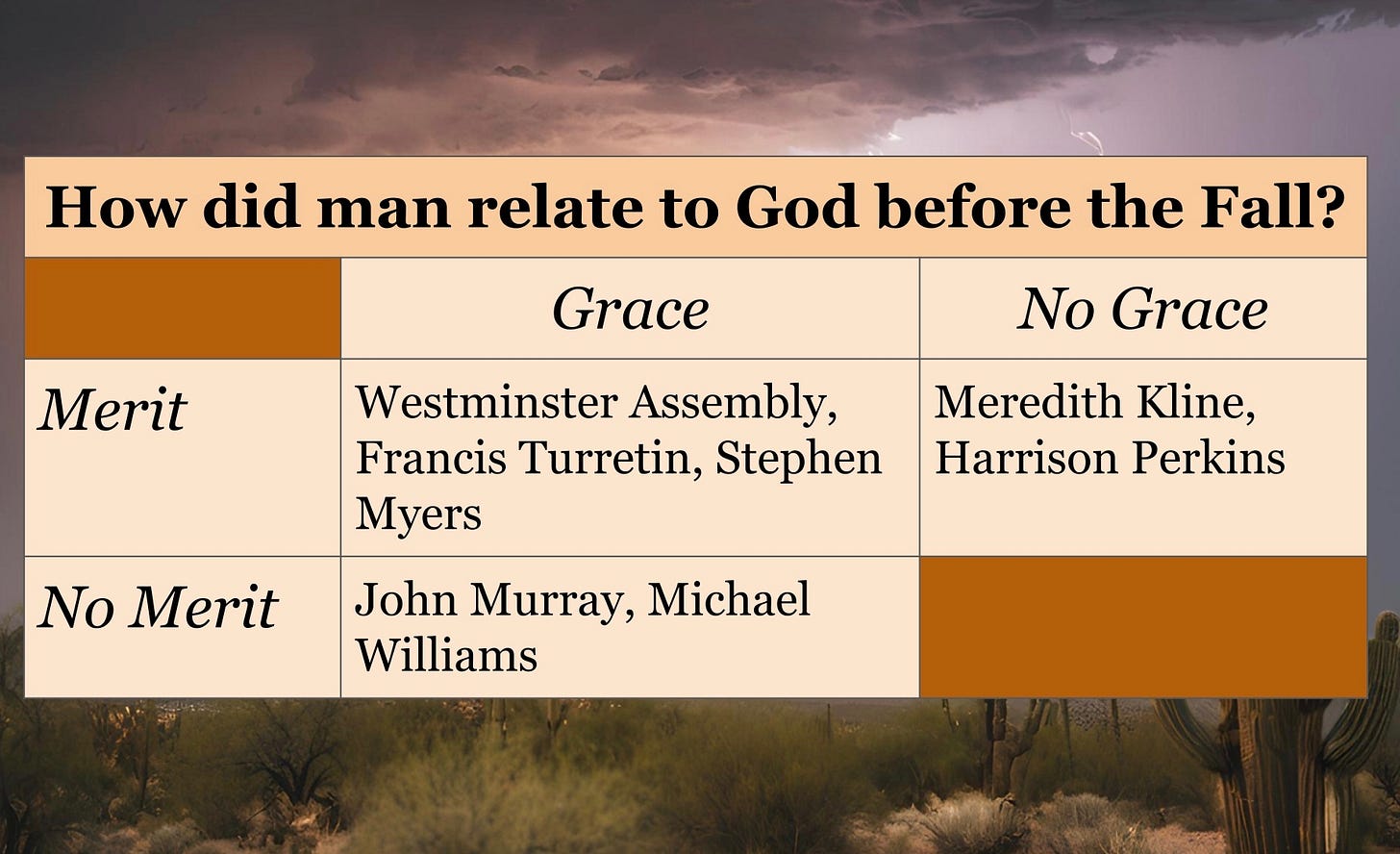

I stumbled back into the theological debate with an intervention on X two weeks ago. First, Kyle Dillon posted this chart about views on grace and merit before the fall:

This post provoked a number of responses.

I ended up replying in a longer thread, providing my objections to grace before the fall. Finally, I anticipated many of the thoughts below in my Saturday livestream, “Is the Secular Sacred?”

The further background was my interview with Dr. Larry Feingold last year. I sprung on him towards the end of the interview that I did not accept the supernatural dimension of the Thomistic vision. But I failed to articulate my desire to follow his account of man’s nature and its natural proportionality. This theological account serves as an answer to the questions I raised there.

Finally, this account is meant to give theological backing to the account of the secular I have been developing in at least four recent essays.

1. No Grace Before the Fall

Hypothesis: Before the fall, Adam was not endowed with divine grace to fulfill God’s commandments.

The recent background of this hypothesis is Reformed disputes about grace and merit before the fall, as mentioned in Kyle Dillon’s original X post.

In recent Reformed theology, followers of Meredith Kline deny grace before the fall, arguing that Adam related to God in a way truly conditional on his obedience, i.e., by law rather than gospel. As a result, merit enters the equation. Should Adam have obeyed, he would have merited eternal life. Our incapacity for merit before God is only on account of the fall, not on account of a metaphysical impossibility, how finite acts could merit infinite reward.

On the other hand, followers of John Murray and then advocates of Federal Vision held that Adam related to God in a way governed by grace rather than strict merit. Obedience was required of Adam, but if he obeyed, he would have to give thanks to God for the spiritual and gracious aid to do so, just like post-fall individuals: “So you also, when you have done all that you were commanded, say, ‘We are unworthy servants; we have only done what was our duty’” (Luke 17:10). In this Adam’s obedience would have been not unlike our obedience as Christians.

The deeper theological background is that of the Reformation itself. One of the Reformed complaints against Catholic theology was its claim that human nature, before the fall, required the assistance of grace not to fall into sin.

The Catholic doctrine of the donum supperadditum was that original righteousness was not natural to man; natural to man was a conflict between reason and the passions. God’s gift of original righteousness ensured harmony between reason and passions. Accordingly, the loss of original righteousness was really just a return to man’s natural state. Without the bridle of the donum superadditum, human nature returned to its natural conflict of reason and passion.

The Reformed objected strongly to the idea that human nature was itself flawed, unstable, and imperfect in this way. Original righteousness, they argued, was natural to man. Man was in good working order from the start, in the same way that a newly manufactured machine operates as it should.

However, Catholic teaching had also included, in addition to the bridle on man’s nature (to produce the natural virtues), supernatural grace. This grace equipped man with the theological virtues of faith, hope, and love, which transcend unaided human nature. While in my X exchange, I questioned whether Reformed theologians have a reason to maintain this doctrine, I was informed by Jonathan Ramont that the majority of Reformed theologians were Thomists on this point. While they denied the necessity of a bridle on man’s natural faculties, they accepted that man had supernatural gifts before the fall.

Notice something: In Kline and the Reformed rejection of the donum superadditum, we encounter an insistence on the naturalness of Adam’s state, and the goodness of that natural state. However, in Murray and the Reformed acceptance of theological virtues before the fall, we have provision for supernatural elements before the fall.

But given the Reformed belief in the goodness of nature, I question why we must accept the presence of supernatural aid before the fall. Why think that Adam had such gifts? Did he need them in order to righteous? And why call such gifts grace, since man had not yet sinned?

The first answer to these questions is that the construction of the covenant of works requires them. If man in the garden was offered a covenant of works in order to move beyond his state of innocence and finite flourishing to one of confirmed righteousness and eternal life, then he would require greater virtues than those required for simple innocence and finite flourishing.

The second answer is that, while Kline proposes a definition of grace as demerited favor, the Thomistic tradition understands grace to refer to all unmerited favor and all supernatural aid to man.

My proposal is that we can reject those two answers and hold that Adam was unaided by grace before the fall. But that requires first addressing our next two topics.

2. No Covenant of Works

Hypothesis: God did not offer Adam a supernatural end in a covenant of works; he only presented Adam with a trial and a positive command to test him.

The covenant of works is a Reformed doctrine that I have come, more and more, to see as a holdover of Catholic supernaturalism.

John Murray questioned the covenant of works, but his objection was more to the title. The Westminster Standards had already called the covenant “the covenant of life” to accommodate such objections.

My objection is quite the opposite. I think obedience to God’s command concerning the tree of the knowledge of good and evil was a matter of strict justice. To fulfill the commandment would not be the result of God’s grace, but of human obedience. To break the commandment would result in demerit and guilt and would reflect on man, not on the insufficiency of his divine equipment.

(And another important question: If Adam had plentiful divine grace, why did he fall?)

Now Adam’s obedience would not have merited anything additional. Simply not breaking God’s one commandment would not entitle Adam to partake of the tree of life, for instance. Rather, Adam, so long as he obeyed, could only say, “We have only done what was our duty. (Luke 17:10b).

(But N.B.: Adam would not, however, have said, “We are unworthy servants” (Luke 17:10a).)

Now if there was no covenant offering to man a supernatural end — eating of the tree of life, confirmed righteousness, and eternal life — then man did not require supernatural aid to fulfill it. His natural faculties and exhibiting the natural virtues would have been sufficient.

According to Ramont’s research, while holding this would place me in the Reformed minority, I would just be echoing Thomas Goodwin:

Thomas Goodwin (1600-1680) presents an interesting case study in the midst of this brief survey as he held a very strong distinction between the natural and supernatural orders but denied that man was originally created for a supernatural end in any sense. Goodwin holds that the first man was in “the estate of pure nature by creation-law,” and that God’s covenant with him was established merely “by virtue of the law of his creating them, and as by their creation they came forth of his hands.” This means that “his knowing God, and the image of God in him, were thus natural,” and his righteousness “whereby he was justified was no other than that natural righteousness in which he was created,” then “the reward, the promised life and happiness that he should have had for doing and obeying, was but the continuance of the same happy life which he enjoyed in paradise.” For Goodwin, the revelation of the covenant, the faith which received it, and the end of it, were all natural in mode. This is a very rigorous expression of that principle of proportionality between means and ends.

Count me a Goodwinite. And note that, if we reject the offer of a supernatural end, the necessity of supernatural aid and grace before the fall is abrogated.

In Catholic theology, it was controversial for recent neo-Thomists to return to the insistence that God could have created man in a state of pure nature, without injustice.

My Protestant proposal is that that is what God in fact did: God created man in a state of pure nature.

3. Grace Is Not Metaphysical, But Moral

Hypothesis: Grace denotes the goodness of God toward sinners, in his acts of redemptive-history, and chiefly, the Incarnation and Atonement of Christ, and its application to us by the Holy Spirit.

In much of Thomas Aquinas’s thought, grace appears as a synonym for supernature, that which cannot be explained by natural powers. However, this is a metaphysical definition of grace. By this definition, the plagues upon Egypt were gracious in virtue of their miraculous character. (They were, in fact, part of God’s grace toward his own people.)

But this is to equivocate on the word grace. If you study Aquinas’s doctrine of grace, with respect to the theological virtues, you find that it is basically synonymous with the Holy Spirit. We Protestants believe that we do not obey God as Christians by our own power alone. We obey him by the indwelling of the Holy Spirit. That is grace.

What is more, grace, like mercy, only makes sense in the context of guilt or demerit. Else it ceases to be a moral category and becomes only a metaphysical category.

But the Protestant insistence is that man’s predicament is not fundamentally metaphysical. His finitude and his physicality are not that from which we must be saved. Salvation is not metaphysical transformation.

Rather, man’s predicament is moral, sin and guilt. God’s grace in our salvation is a response to the human state of sin and guilt, and resultant misery.

If we reject the use of “grace” to refer generically to anything supernatural, then we find that grace only begins after the fall. And I indeed follow my teachers in thinking that we see this grace almost immediately after the fall: God kills an animal in order to clothe Adam and Eve, covering their nakedness and shame. And in Genesis 3:15, God promises Christ to crush the head of the serpent.

I love grace; I just think it came after the fall.

4. Christ’s Human Nature Is Just as Ours

Hypothesis: Christ’s human nature was like ours in every way, yet he did not sin.

Many accounts of Christ’s nature during his life introduce supernatural virtues into his human nature or divinize that nature in some way. As in his account of Adam, Aquinas attributes to Christ the supernatural virtues. Now, I think this is correct. Christ comes after the fall, he is tasked with something much greater than obedience to the natural law — self-sacrificial love — and Scripture explicitly says that he was filled with the Spirit.

And yet, these virtues are not the product of Christ’s divinity. They are gifts to his human nature (subsequent to his baptism). Likewise, they are gifts that he then distributes to us in the application of redemption.

What is more, they do not fundamentally transform his human nature but aid it.

The real trouble with Aquinas’s view is that he attributes to Christ the beatific vision even in his humiliation. This attributes to Christ the benefits of his glorification even in the midst of his humiliation. It ends up denying that Christ went through a human process. It risks denying Christ’s need for the theological virtues; if Christ could see God, he did not need faith. If Christ already had the beatific vision, he did not hope. This doctrine, I am afraid, compromises the true humanity of Christ. It renders his obedience and his temptations illusory.

(This puts such doctrines adjacent to the ancient heresies of Docetism, Eutychianism, and Apollinarianism.)

Martin Luther held that Christ’s human nature, by the communication of properties, possessed the divine attribute of omnipresence, i.e., ubiquity. The Reformed objected the Christ’s human nature was a truly human nature. It was limited in location. After his ascension, that nature was in heaven, not on earth. Christ is absent in body, but present in spirit, that is, in the Holy Spirit.

The Lutherans called this Reformed insistence the Extra Calvinisticum. But it wasn’t extra. It was just Chalcedonian Orthodoxy, from which Lutheran theology had departed in distributing ubiquitously Christ’s human nature.

Like the Catholic and Lutheran doctrines, many Christians today attempt to divinize Christ’s human nature. In an attempt to protect Christ from sin and misery, they attribute to him properties that cleanse him of participation in our nature.

One such attempt is the contemporary conservative Reformed teaching that Christ did not experience internal temptation.

By drawing a sharp line between Christ’s temptations — merely external — and ours, internal, Christ is, in fact, freed from the experience of temptation. (Even Doug Wilson agrees.) Apparently, temptations were merely in Christ’s vicinity, but luckily, none of them tempted him, because he had no passions or desires to sin.

But this is to deny Hebrews 4:15: “He was tempted in every way as we are, yet without sin.”

Without internal temptation, it is not possible to be tempted. On this view, it was impossible, even according to Christ’s human nature, that he sin. This would make his temptations illusory. (Many defend this doctrine in the name of Christ’s impeccability. See R. C. Sproul defends Christ’s peccability here.)

On the contrary, I would argue with Irenaeus that Christ went through a true process of human development and the trials of temptation. What we experience, Christ experienced, yet he did not sin.

Because he was tempted as we are yet without sin, he is able to comfort us. He is also living proof that there is a way out of temptation. There is no temptation we experience that it would have been below Christ to experience, or that he could not have resisted. Therefore, we can resist these also. (And the mere experience of temptation is not sin.)

In fact, Christ learned and possessed virtues, both natural and theological, in order to do battle with real temptation, trial, and suffering. Only because he assumed this fulness of our postlapsarian (post-fall) human experience can Christ save us.

What he has not assumed he has not redeemed.

5. Felix Culpa and Maturity

Hypothesis: The purpose of human history is that we should be transformed from innocence to maturity, with the fall and redemption being necessary steps along the way.

Adam’s state was not one of virtue, but innocence, and the purpose of the whole of human history was to transform man from innocence to maturity.

Following the church father Irenaeus, I hold that man’s natural state before the fall was not one of virtue but of innocence. Not only did man lack the theological virtues; he lacked the natural virtues.

But wouldn’t that mean that Adam had vices? No. His behavior, prior to the fall, conformed to God’s natural law, but not because of virtue but of innocence, a kind of natural, original righteousness.

Accordingly, man’s moral state was radically insufficient. Given a single temptation, he immediately fell. Adam lacked virtue; hence, he fell.

By contrast, the Catholic and Reformed attributions to Adam of every virtue make the fall inexplicable and redemptive-history needless.

Rather, the fall was a necessary step on the path to maturity. (O Felix Culpa! “Happy Fall.”) It was, after all, the tree of the knowledge of good and evil from which Adam and Eve ate. It was the tree that exposed their nakedness and introduced shame.

Relative to the ordinary course of human life, the Fall was man’s puberty. Accordingly, it is not naïve innocence that God desires, but obedience after we learn how the world works and learn of the existence of evil as well as good. (Restored prodigal sons, not older brothers.) Such obedience requires maturity. It is not freedom from temptation, but strength in the face of temptation.

This is why Christ had to endure the same sufferings and temptations as us. It is why he had to live a full human life.

Jesus told us that what God required was not just Pharisaical obedience; it was perfection, i.e., maturity: “You therefore must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect.” (The word translated “perfect” is elsewhere translated “mature.”)

Accordingly, maturity is also the purpose of our own lives. We cannot accept merely the Abridged Gospel, that Jesus came to save us only from the guilt of our sins. No, he came in order that the righteous requirement of the Law might be fulfilled in us. He came that we might become perfect, i.e., mature:

Until we all attain to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to mature manhood, to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ, so that we may no longer be children.

— Ephesians 4:13-14

6. Man’s Final End Is Proportionate to His Nature

Hypothesis: Man’s final end is resurrected, bodily experience of natural, human flourishing, together with ever-increasing knowledge of God, in accord with our finite mode of cognition; man’s final end is proportionate to his nature.

What is the point of it all? If man was not offered a supernatural end in the Covenant of Works, then Christ did not fulfill the Covenant of Works on our behalf.

Instead, Christ came that our nature might be perfected. He came that the innocence which had been transformed to shame might be transformed to maturity.

Why? So that God’s relationship to us might change from that of an innocent son to a mature spouse, united by a covenant.

There is no covenant in the garden because the natural relationship of Creator to creature does not require one, any more than that of father to son requires a covenant.

But a relationship of maturity and marital union requires a covenant, and it requires maturity of both parties:

Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her, that he might sanctify her, having cleansed her by the washing of water with the word, so that he might present the church to himself in splendor, without spot or wrinkle or any such thing, that she might be holy and without blemish.

— Ephesians 5:25–27

The Catholic teaching is that men’s final end is supernatural. It was offered over and above his natural end. And it is to behold God through his essence, in the beatific vision.

Yet in Aquinas’s and the resultant Catholic account, this mode of knowledge of God is above the capacity of our nature. In fact, it is a kind of infinite knowledge, even a divine mode of knowledge. Accordingly, it requires miraculous transformation of our nature for us to experience. It leaves our nature in the dust.

But what if man’s final end is not supernatural, transcending his natural end, but a perfection adorning his nature? What if it is mature virtue in contrast to naïve, but sinless innocence?

And then, what if our final end is to live fully human, bodily, physical lives of human flourishing together with ever-increasing knowledge and love of God, according to our finite mode of cognition?

Aristotle articulated the difference between an actual infinite and a potential infinite. Contrary to contemporary mathematicians, he argued that an actual (numerical) infinite was impossible. But a potential infinite, the hypothetical or asymptotic limit of, for example, exponential increase may exist. There are an infinite number of natural numbers, but this infinity consists in the endless possibility of adding one more.

What if the infinity of what God has prepared for us is like this? We will ever increase in our knowledge of God. The progress will never end. Time will never stop. And the perfection of our finite nature will be to endlessly and asymptotically know more of God and his goodness, in accordance with our nature.

(It goes without saying that this is the vision of C. S. Lewis in the final chapters of The Last Battle.)

Further up, and further in.

Disclaimer

I do not assert this theological vision. I hypothesize it. I do not think it has been fairly considered. And I think it is a candidate to be a truly Protestant account and a merely Christian account.

Let me know in the comments what you think.

Further Reading

Here are several books I’ve been reading in the last weeks that helped to inspire this theological vision:

Julie Canlis, A Theology of the Ordinary

Jordan Raynor, The Sacredness of Secular Work

, The Light in Our Eyes: Rediscovering the Love, Beauty, and Freedom of Jesus in an Age of Disillusionment (Forthcoming)And an article:

, Patient Kingdom, “Blank Slate Theology vs. A Theology of Continuity”The Catholic Works on Nature and Grace that inspired me:

Lawrence Feingold, The Natural Desire to See God According to St. Thomas and His Interpreters

Steven Long, Natura Pura: On the Recovery of Nature in the Doctrine of Grace

And Bonhoeffer and Brunner, who have played an important role

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Ethics (esp. the sections on “The Natural” and penultimate things)

Emil Brunner, Man in Revolt and The Divine Imperative

And my own formative study of Aquinas’s anthropology:

“Wounded, But Not Destroyed: Thomas Aquinas on the Effect of the Fall on Human Nature”

Obviously Christian naturalism is distinct from the philosophical doctrine of naturalism, according to which what the natural sciences describe is all there is. As a Christian, I don’t think the natural sciences exhaust what can be said of nature anyway. Instead, Christian naturalism offers a constraint on theology, that what it describes be consistent with human nature and its goodness as the object of God’s creation.