Abigail Favale’s The Genesis of Gender

This book is philosophical and theological in the highest senses. It is concerned with timeless truths of the human condition, addressed at a particular time when they most need articulation.

Abigail Favale’s The Genesis of Gender: A Christian Theory is the best book I have read in a long time. As a baseline, this is because of its timeliness. The matter of transgenderism, as it has been called, is the heart of the present culture war. It is where a voice of clarity and truth is most needed and needed now.

However, The Genesis of Gender is not a culture-war kind of book. It is a book that is philosophical and theological in the highest senses. It is concerned with timeless truths of the human condition, addressed at a particular time and place when they most need articulation.

But The Genesis of Gender is also a book that is beautifully written, that speaks truth in love, and unites the form and matter of what it says. I myself am a student of analytic philosophy. Analytic philosophy actually has great matter; it addresses many of the timeless difficulties and confusions of human thought. But it has a terrible form: Endless acronyms, numbered premises, and scrupulous attention to minute details to prove trivial conclusions.

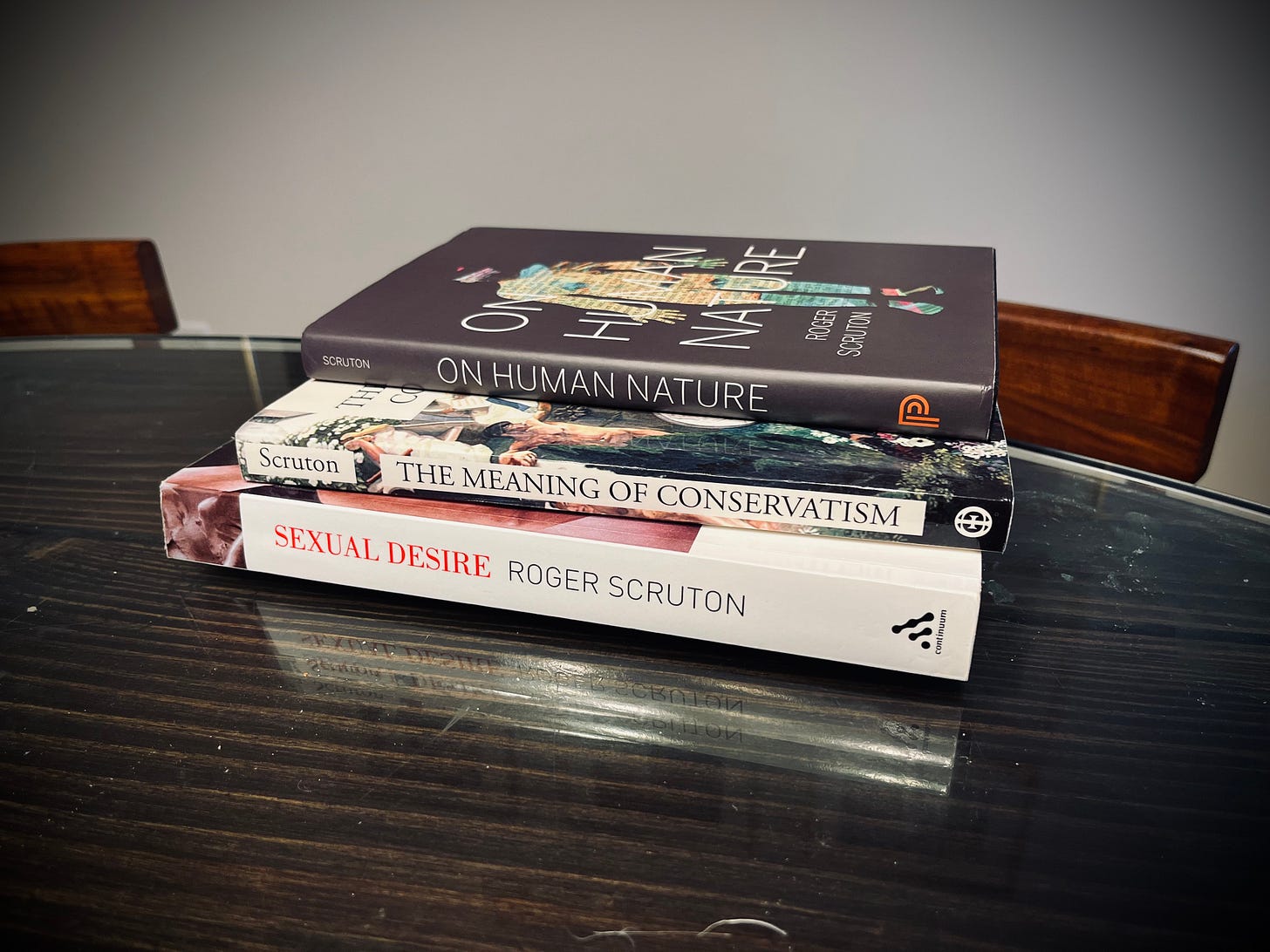

Where I have seen the matter of philosophy united with its form is in the works of Roger Scruton. Works like The Meaning of Conservatism, Sexual Desire (a better comparison for this book), Beauty, or Human Nature - these books present philosophy as a form of literature. These remain my model, and I search far and wide for philosophy, and even more rarely, theology, that attains this unity of form and matter. (Other examples include books by Wendell Berry, Alain de Botton, and Tom Hodgkinson, to name a few.)

The Genesis of Gender is such a book.1 Favale’s knowledge of the specific disciplines of sexuality and gender studies, philosophy, and theology, and her apt literary and mythological references reflect the fruit of the kind of bookish wisdom we partisans of the liberal arts continue to believe in.

Consider her reference to Ovid’s Metamorphoses:

We are living in the Age of Pygmalion, that master artist from Ovid’s Metamorphoses who wants a wife but despises real women. He picks up his hammer and chisel and constructs his ideal out of stone. He lusts after her; his image of woman is more desirable than the reality. In the original myth, Pygmalion wants to marry her, to bring her to his bed; in our time, Pygmalion wants to be her. Instead of a sculptor’s tools, he works with scalpel and syringe. Instead of stone, he carves his fantasy into his own flesh. (159)

I am speechless. We are living out errors that were adequately addressed and cautioned against by ancient mythology, and not only the secular public but even the Christian church is ignorant.2

In places, Favale summarizes the history of gender theory, some of which was already familiar to me - I remember googling John Money back in high school. But because of the comprehensiveness of her summary, she included things, for example about Margaret Sanger, that I have simply never heard. To see Sanger’s philosophy, her role in introducing the idea that the standard of female freedom is maleness and that contraception and abortion are what will facilitate this liberation, lays bare the origins of both feminism and gender theory. The description of the difference between the first recipient of gender-reassignment surgery in the 1930’s and the next in the 1950’s - the first wanted to give birth to children, the latter simply to physically appear female - makes Favale’s point without her having to say much else: The vision of gender that we have received is separate from reproductive function and purely aesthetic.

As a work of Christian thought and theology, The Genesis of Gender stands out for its combination of orthodoxy and depth of Christian theology and engagement in history, philosophy, and science. This is what I call Christian empiricism. Unlike a form of theology I have often encountered, call it Christian coherentism, that treats Christianity like a self-enclosed bubble, an orthodoxy that must be maintained but can hardly be propagated, Favale’s approach shows the Christian account to be deeply adequate to and rooted in empirical reality.

One of the main examples of this comes toward the end of the book, as Favale recounts several stories of de-transitioners. I too have watched many of these stories and interviews.3 I have primarily heard these interviews on shows run by interviewers who are not Christian but cannot deny what they see and hear from these individuals.

By comparison, my own Christian training at a Christian college and as a seminarian did not involve this sort of empirical knowledge; it treated it as a matter of parochial Christian doctrine that we believe that there are men and women, sexual dimorphism. But this way of approaching things suggests that there is no conformity between the world of common human experience and what the Bible teaches. In doing so, it forfeits many of the strongest means of preparation for the gospel, which are rooted in God’s revelation through nature, the natural law, and common human reason.

The stories of de-transitioners reveal very directly that men are not women and women are not men. The scars, incisions, continuing bleeding, and irreversible hormonal change are the proof. It has been said before, but the Church needs to be ready with a message of hope for those harmed by this denial of nature, and it needs to make appeal to commonly understandable experiences like these as evidence of the accuracy and power of, for example, the biblical creation narrative.

My own dissertation will, I hope, be on the philosophy of language, so let us turn there briefly as well. Favale discusses how the reality of sexual dimorphism is often undermined by the possibility of exceptions to any purported “definition” of man or woman. After all, some women do not have uteruses, some (many) women do not ever give birth, and so on. Nevertheless, Favale attempts a definition in terms of the ordering of the body to the production of either small or large gametes, itself a valiant effort.

I would simply offer two interventions from analytic philosophy of language. The first is that the natures of natural kinds, existing divisions in nature, are not representable in verbal definitions summarizing essential properties. This I gather from Saul Kripke’s Naming and Neccessity, and I have explained further here. But the short of it is that the meaning of a term like “woman” is the natural kind that are women. We can proceed to offer properties that women have, but our use of “woman” is not dependent on confirming that individual beings have the relevant properties. Things are the other way around; we observe a natural classification, a natural kind, and then we try to express verbally what holds of it, to quote Aristotle, “always, or for the most part.”

The second intervention is on that last point. This is less known, but comes from the philosopher Michael Thompson’s essay, “The Representation of Life.” He discusses there the logic of generic sentences, sentences about kinds of things, especially kinds of living things. He notes that when we speak about a kind or a species, we speak in generalities. We do not intend what philosophers call “a universal generalization,” a statement that holds for every last one. Instead we speak about what happens to an individual of that kind when things proceed normally. For some species this is very rare: “Although ‘the mayfly’ breeds shortly before dying, most mayflies die long before breeding” (Thompson, Life and Action, 68). In fact, our culture’s entire difficulty with stereotypes stems from a failure to comprehend this point about generic sentences.

These two points from the philosophy of language would go a long way in the gender debate.

Still on the topic of language, Favale’s approach to trans-identified individuals and pronoun use is particularly careful, thoughtful, conscientious, and loving. Favale’s reticence to use preferred pronouns is explained in autobiographical detail. Compassion has compelled her to do everything she can to interact well with trans-identified individuals. However, her Christian conscience forbids her from misrepresenting reality in her speech. My conscience commands the same, though I cannot claim to have had opportunity for this to be much of a live issue. The combination of truth and love about which she speaks eloquently, she truly exemplifies in the book’s final chapters.

There is much more to talk about from Favale’s book, and I hope to dig into matters of postmodernism, sexual dimorphism, scientific studies and more in the future, in developing a Christian approach to these matters. But Favale has done the legwork, and she is the right person to write the book. In my Christian life, I have grown to trust most on intellectual matters converts, not those, like myself, who are and have always (more or less) been conservative, orthodox Christians. While coming from an evangelical background, Favale studied gender theory and followed it as far as she could, testing its limits by experience. Nevertheless, while not doctrinaire, her book is orthodox, not by any policing of doctrinal boundaries, but by tasting and seeing that the Lord is good. Having put the claims of Christianity with regard to human sexuality to the test, she discovers for herself and testifies to us that they are good, true, and beautiful.

I’ll finish simply by saying that The Genesis of Gender is the kind of book I would hope to write. Its unity of philosophy, theology, social science, literature, and history certainly goes beyond my capacity. Nevertheless, I have the ambition to complete a book I have outlined and begun to draft, under the working title of Marriage for Millennials. I hope to present an understanding of marriage as rooted in nature and in sexual dimorphism as a perennial possibility for human living and a human birthright, not a parochial religious distinctive. If I can write with a fraction of Favale’s grace and ability, I would be pleased.

The Genesis of Gender: A Christian Theory will stand as a great and timely Christian account of the human condition. May it strengthen Christians, instruct the ignorant, and convert the confused. I wholeheartedly recommend The Genesis of Gender.

I’ll leave aside the beauty of the publication and the formatting of the book - credit to Ignatius Press.

Not to mention that this PhD-pursuing amateur is entirely unfamiliar with Ovid and his Metamorphoses.

Most of those I have watched have been from females; right now, I am mid-way through an interview with Ritchie Herron that I find much more difficult, as a man, to bear to hear. It hits home.