Why Not Theistic Evolution? Part 2: The Typological Pattern of Biology

While some think appeals to evidence are fruitless, there are evidential standards for deciding whether life and the variety of species are explained by an evolutionary process or direct creation.

In 1802, Anglican philosopher William Paley published his Natural Theology or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, an influential version of the argument for the existence of God from biological design. In the work, which featured many descriptions of biological features, like the eye, as evidence of divine design, Paley popularized the metaphor of God as watchmaker.

In 1986, British biologist Richard Dawkins published The Blind Watchmaker: Why the Evidence of Evolution Reveals a Universe without Design, an influential work of biological theory but also a founding work of the “New Atheism.” As the title reveals, Paley’s Natural Theology was a direct target of Dawkins’ argument.

Here at “The Natural Theologian,” a major theme of the newsletter is that the category of “nature” should have a place in Christian theology. Likewise, I have argued that empirical sources of information, like the sciences, (but also philosophy,) are valid and important grounds of knowledge. Calling that source of knowledge into question inclines many toward the view of six-day creation, as I discussed here; but accepting science as a source of knowledge inclines many others toward a theistic evolutionary view of origins.

However, I believe that the scientific evidence for the intelligent design of biological organisms points toward limits to variation within biological kinds. This leads me to an old-earth creationist view, accepting a long geological and cosmological history, but requiring the creation of new biological kinds throughout that history.

This is the second post in my series on why I do not hold to theistic evolution. In the first, I explained the terms of debate and my motivation for writing. In this post, we’lll begin to consider the scientific evidence against evolution.

While some think appeals to evidence are fruitless, because we only see what our presuppositions, worldview, and cultural background incline us to see, there are evidential standards for deciding whether life and the variety of species are explained by an evolutionary process or direct creation. In this post, we consider the following standard: Creationist and evolutionary theories posit different trees of life, and a look at the evidence of both contemporary and ancient biology can confirm one or the other. In particular, evolution posits a tree of life that is gradual, including many transitional species, in order for natural processes to lead to the variety of species. A tree of life that has a typological pattern, where types are clearly distinct from one another and transitional species are absent, is only compatible with a creationist explanation, with the exception of micro-evolutionary change.

As I will argue, the evidence gathered by Michael Denton, in his Evolution: A Theory in Crisis, published in the same year as Dawkins’ Blind Watchmaker, 1986, points decisively to a typological shape to biology, and therefore, a creationist explanation.

The Typological Shape of Biology

Evolution: A Theory in Crisis is one of the earliest works of the Intelligent Design movement. Notably, the author, Michael Denton, is not a Christian believer, unlike the majority of Intelligent Design advocates. In his later work, Denton argues for a teleological evolutionary view, as per the book’s title, Nature’s Destiny. Nevertheless, he argues that biology does not reveal a gradual and transitional structure but rather a typological one.

Denton surveys multiple lines of evidence, but especially the morphological and biomolecular, in order to show that biology fits the typological pattern, in which organisms exhibit clear differentiation from one another and transitional species are not to be found. We’ll examine the fossil record in the next section, but in this section, we’ll focus on the evidence from morphology and biochemistry that reveals typological differentiation, rather than a gradual, evolutionary and developmental pattern of the tree of life.

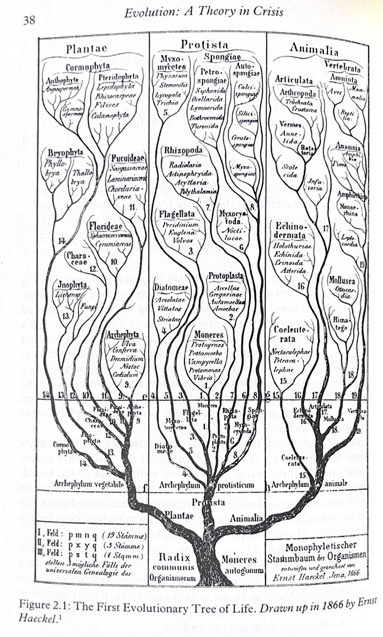

While the theory of evolution introduced the idea of universal common ancestry, the same tree of life that Darwin proposed was already in use, but merely as a tool of taxonomy. Biologists who did not believe in universal common ancestry had never had any trouble classifying kinds of organisms in terms of their similarities and differences, treating groups as more or less related, not in terms of ancestry but biological organization. Homology, the study of similarities of biological organisms, preexisted Darwinian theory and was not perceived as giving evidence of common ancestry but of common design.

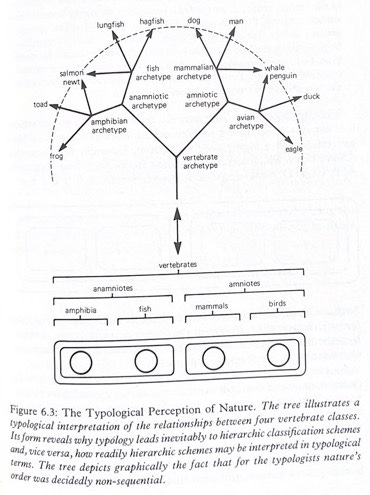

Nevertheless, non-evolutionary and evolutionary interpretations of taxonomy are not merely different interpretations of the same evidence. Each predicts and depends on different patterns of taxonomy. Non-evolutionary taxonomy depends on and predicts a typological organization of nature, on which, to quote Denton, “there were absolute discontinuities between each class of organisms, that life was therefore fundamentally a discontinuous phenomenon and that sequential arrangements, whereby different classes were linked together or approached gradually through series of transitional forms, should be completely absent from the entire realm of nature” (98). This perception and theory of nature was called “typology,” and as Denton continues, “Typology contrasted completely with the idea of organic evolution” (98).

This contrast results from the entirely different expectation of evolutionary theory with regard to taxonomy. Denton summarizes the kind of taxonomic patterns that give evidence of evolution: “Evidence for evolution exists in nature wherever a group of organisms can be arranged into a lineal or sequential pattern, in which case the idea of evolution becomes almost irresistible.” Evolution requires that thereby gradual and continuous sequences of intermediate forms, rather than discontinuities between types of organisms.

But which pattern does nature show? To summarize, while there are many particular sequences that may evidence evolution within a biological kind, and some that certainly do, there are great discontinuities among living things, especially at the higher taxonomic levels of life.

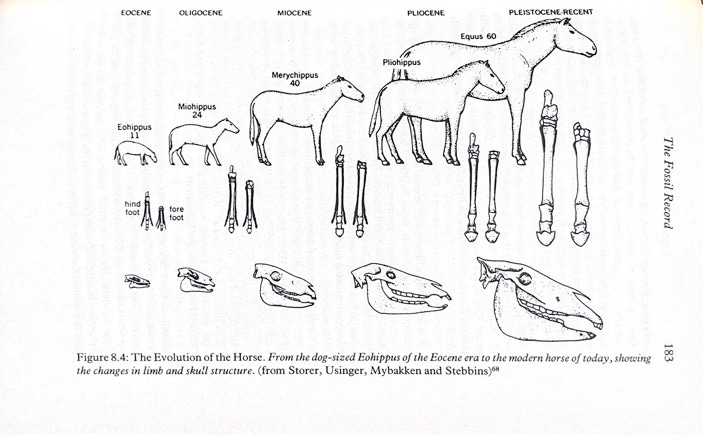

Some evolutionary sequences are historical and persuade many: “A classic case is the series of fossil horses. This series is nothing like a perfect continuum of forms, the breaks are distinct and clear, but the overall sequential pattern is so obvious that no one seriously doubts that the modern horse has evolved from the primitive horses of the Eocene era sixty million years ago.” (“No one seriously doubts” - I know of at least one counter-example.)

However, most clearly at higher levels of organization, as Denton puts it, “it can hardly be denied that there has always been massive empirical evidence for the typological model of nature within the existing realm of life.” He continues:

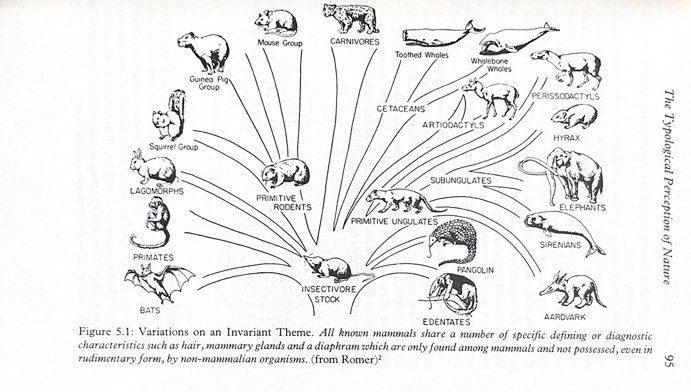

Admittedly, the axioms of typology have been shown to be inapplicable at the level of the species. Species can and do evolve and many can be linked to other species through clear sequences of intermediate subspecies; consequently, distinct demarcations cannot be drawn at the lowest taxonomic levels. But, at levels above the species, the typological model holds almost universally. Indeed, the isolation and distinctness of different types of organisms and the existence of clear discontinuities in nature have been self-evident for centuries, even to non-biologists. No one, for example, has any difficulty in recognizing a bird, whether it is an eagle, an ostrich or a penguin; or a cat, whether it is a domestic cat, a lynx or a tiger. Moreover, no one can name a bird or a cat which is in any sense not fully characteristic of its class. No bird is any less a bird than any other bird, nor is any cat any less a cat or any closer to a non-cat species than any other cat. (105)

At lengths to which I cannot here go, Denton details the way in which past, fossilized species also exhibit the same typological and discontinuous character as observation of nature reveals among organisms now living. After surveying the evidence of morphology (the structure of organisms), he surveys the biochemical level and finds the same typological differentiation. Except for variation at the lowest taxonomic levels, which are variations on an archetype, nature exhibits a discontinuous, typological structure, incompatible with universal common ancestry, not to mention neo-Darwinian mechanism.

Denton concludes:

All in all, the empirical pattern of existing nature conforms remarkably well to the typological model. The basic typological axioms – that classes are absolutely distinct, that classes possess unique diagnostic characters that these diagnostic characteristics are present in fundamentally invariant form in all the members of a class – apply almost universally throughout the entire realm of life. Consequently, the isolation of classes is invariably absolute and transitions to particular character transits are invariably abrupt and the phenomenon of discontinuity ubiquitous throughout the living kingdom. (117)

The Typological Structure of Paleontology

As with morphology and biochemistry, typology and evolutionary theory generate different expectations for and require different evidence of the fossil record. Typology alone merely generates the expectation that all the fossils discovered will conform to a type, rather than be transitional between types. With the general outlines of the fossil record, with its general progression in terms of body-plan across the ages, typology expects that the progression and appearance of life-forms on earth will be discontinuous.

By contrast, evolution - again, as the combination of universal common ancestry and neo-Darwinian unguided mechanism - would predict a gradual and sequential arrangement of transitional forms. In Darwin’s own day, archeology and paleontology were just getting their started, and the absence, at the time, of such evidence was attributed to the early stage of the work. Is the evidence any better in our own time?

Unfortunately for Darwinists, no. Denton tells the story of how the search for missing links took off in the years following the publication of The Origin of Species (158). Denton summarizes the results of the search for living species that could be transitional between existing types:

The seas and land have of course yielded many new species not known in Darwin’s time as zoologists and botanists have extended their explorations into regions unexamined one century ago. A number of deep sea fish species and many invertebrates, both terrestrial and aquatic, have been discovered over the past century but all of them have been very closely related to already known groups, and in the few exceptional cases, when a quite new group of organisms has been discovered, it has invariably proved to be isolated and distinct and in no sense intermediate or ancestral in the manner required by evolution. (159, Italics mine).

The search among fossils has continued apace since Darwin’s time. In fact, “probably 99.9% of all paleontological work has been carried out since 1860” (160). “But virtually all the new fossil species discovered since Darwin’s time have either been closely related to known forms or…strange unique types of unknown affinity” (161). Denton describes several findings of that latter sort, which have required entirely new phyla for their classification but are not even candidates to be transitional species between phyla.

Another important finding from the fossil record is this: “It is still, as it was in Darwin’s day, overwhelmingly true that the first representatives of all the major classes of organisms known to biology are already highly characteristic of their class when they make their initial appearance in the fossil record” (162).

The most telling example remains the event known as the “Cambrian explosion.” (Some have rebranded it the “Cambrian radiation,” or “the “Cambrian diversification.”) In the space of “13-25 million years,” “practically all major animal phyla started appearing in the fossil record” (Wikipedia, “Cambrian Explosion, link). Such discoveries have forced evolutionary theorists to abandon the Darwinian commitment to gradualism and to postulate that evolution happens in great leaps. It hardly needs to be said that, if evolution happens in such leaps, it cannot occur by neo-Darwinian mechanism, nor by any other mechanism known to be at play in biological variation.

The significance of the evidence is overlooked by those who show deference to evolutionary explanations. But it should be recognized that, if evolution occurred by the neo-Darwinian method and on the scale of universal common ancestry, the fossil record would have to look wildly different than it does. Without regard to doubts about the possibility of biological evolution of new types and between types which I will raise in the next post, the fossil record alone tells a story, quite straightforwardly, of the sudden appearance of new kinds, fully formed, and discontinuity between types both in the present and the past. If we ask whether the fossil evidence is that predicted by typology or by gradual evolution and common ancestry, the answer is clear: The fossil evidence points to typology.

You're saying these arguments strengthen the Divine Intervention theory against the theory that life evolved with no external input. Do you think they strengthen to a similar degree the theory that intelligent aliens came to earth and created many separate species here?

Hard to see how evidence against the No External Input theory could strengthen the Divine Intervention theory more than the Alien Intervention theory.

Theistic evolution has always struck me as the worst of both worlds.