Was Machen a Modernist?

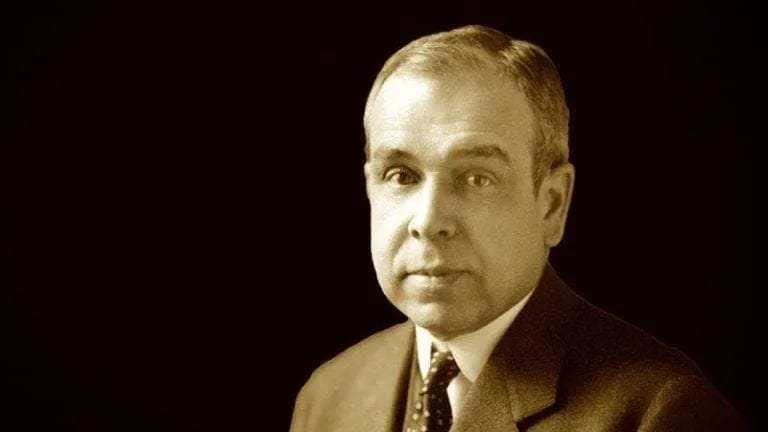

J. Gresham Machen — the champion of evangelical hagiography, or modern scholar, whose embrace of rigorous historical methods placed him closer to the modernists he otherwise opposed?

Was J. Gresham Machen, hero of the Bible-believing side of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy, actually, in some sense, a modernist?

That’s the controversial thesis of Richard E. Burnett’s new biography. In Machen’s Hope: The Transformation of a Modernist in the New Princeton, Burnett — future seminary professor of Gen Z Christian PCUSA YouTuber “Redeemed Zoomer” — argues that Machen, hero of the theological fundamentalists, was strongly committed to the very modern historical and critical methods by which modernists called the Bible into question.

Who Was J. Gresham Machen?

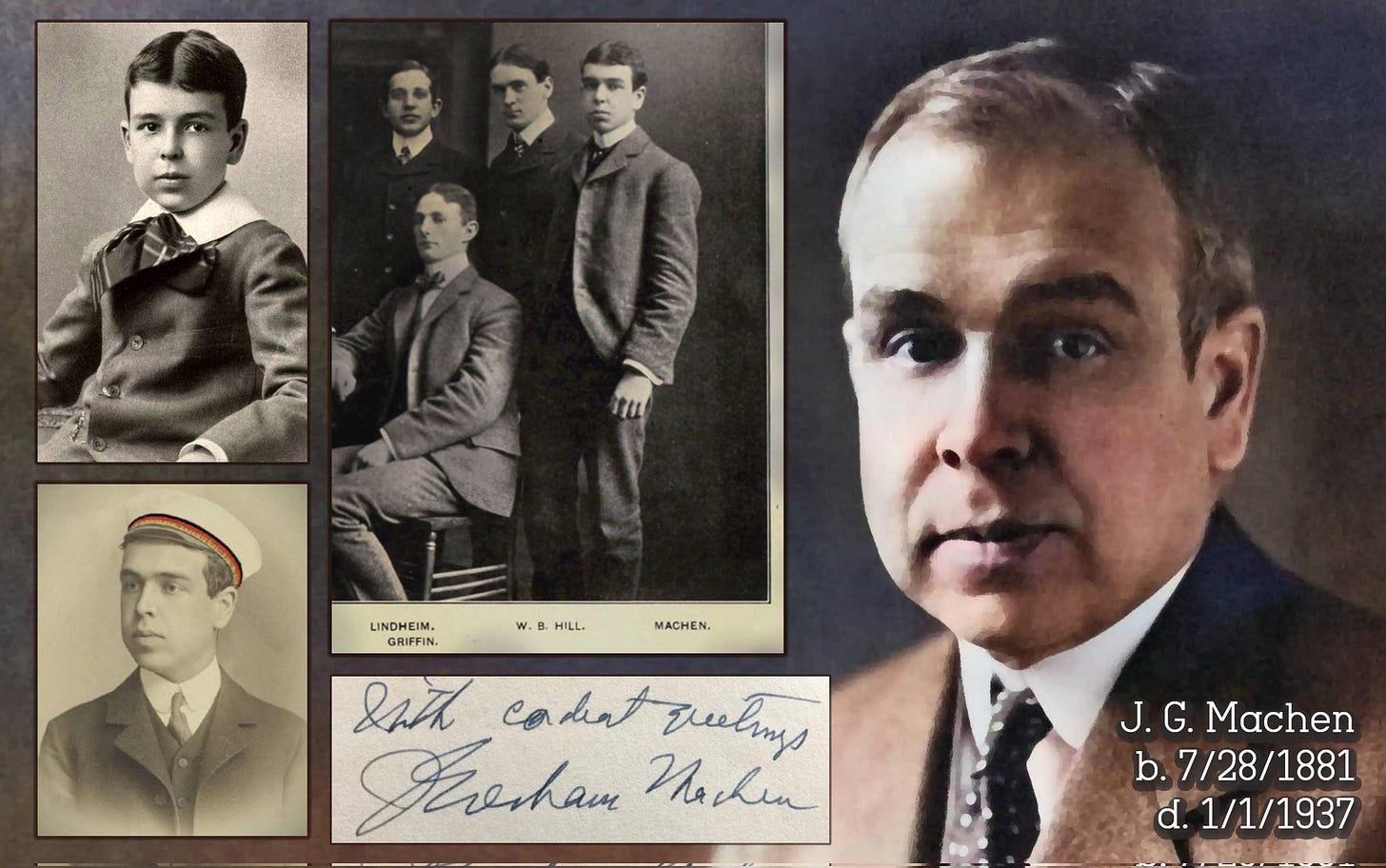

J. Gresham Machen (1881-1937) was the founder of Westminster Theological Seminary and also the founder of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church (OPC), a conservative Presbyterian denomination.

(Both institutions have played formative roles in my life.)

Before that, Machen served as a professor of New Testament at Princeton Theological Seminary and belonged to the northern mainline Presbyterian Church, now the PCUSA.

Through a complex set of circumstances, Machen became the intellectual leader of the fundamentalist movement, reacting against the modernism and theological liberalism of the early 20th century.

In the previous biographies of Ned Stonehouse and D. G. Hart, Machen receives something of a hagiographic treatment. He is portrayed as a defender of the Old Princeton of Charles Hodge and B. B. Warfield, firmly standing on the Bible-believing, if not fundamentalist, side of the controversy.

But Dr. Burnett’s book complicates this picture. While he acknowledges Machen’s later transformation to a conservative stalwart, he demonstrates that, in significant ways, Machen aligned himself with the modernist academic approaches of the “New Princeton.”

What Are Modernism and Fundamentalism?

Let’s clarify some terms.

First, “modernism.” Theologically, modernism attempts to rework Christian theology to be more amenable to modern thought and the scientific method. Modernists tended to downplay Christ’s divinity, seek the “historical Jesus,” and reduce His teaching to purely ethical principles. This theological liberalism often denies key doctrines like the virgin birth, Christ’s divinity, His miracles, and chiefly His bodily resurrection.

Fundamentalism, by contrast, was a reaction against such liberal tendencies. Early 20th-century fundamentalists rallied around “five fundamentals,” including the inspiration of Scripture, the virgin birth, and the resurrection. However, the fundamentalist movement was often anti-intellectual and minimal in its doctrinal commitments, reducing Christianity to these core essentials. (And often combining it with the new sub-cultural commitments of dispensationalism and teetotalism.)

Machen, however, was different. He stood for the older Presbyterian tradition that embraced the full Westminster Confession of Faith—a detailed doctrinal statement far more expansive than the five fundamentals and including Calvinistic doctrines not shared by all Christians. In their biographies, Hart and Stonehouse have highlighted these ways in which Machen was not exactly a fundamentalist.

But they neglected to show Machen’s commitment, not to the theological conclusions, but to the methods of the modernists, chiefly, objective, worldview-neutral historical-critical study of the Bible. It is to this modernist commitment that Dr. Burnett shifts the discussion.

To understand Machen’s methodological modernism, we need to look further into his life.

The Life of Machen

While the populist, fundamentalist movement tended to draw from working- and middle-class Christians, Machen came from Southern gentleman-stock in Baltimore. His family were closely adjacent to the founding of Johns Hopkins University, which stood out in the American landscape for adopting the German research university model — focusing on rigorous research rather than purely liberal arts or religious training.

The Machen family knew many of those involved with that University, including its first president, Daniel C. Gilman. They knew Woodrow Wilson, Presbyterian president of Princeton University, and future U.S. President. The Machens were also deeply connected to the northern Presbyterian denomination and knew many of the leaders of that denomination.

Machen’s German Studies and Scholarly Rigour

After his undergraduate study at Johns Hopkins and Master’s at Princeton Seminary, Machen studied under leading biblical scholars in Germany, many of whom were undermining traditional Christian supernatural claims. These scholars argued that historical-critical study of the Bible made it impossible to accept many traditional doctrines at face value. While some retained a form of faith, they often refashioned Christianity into a purely ethical or pietistic system, disconnected from historical events.

Though Machen rejected their theological liberalism, he deeply admired the German modernists’ rigorous scholarly methods.

However, Machen’s mother worried that his openness to historical methods would lead him away from his faith. Machen responded to this worry in a letter to his father:

“Mother’s mistake is the old, old mistake of the orthodox, which shows how uncertain they often are of their position. … To investigate only one side of the question because to investigate the other side is dangerous simply shows that you really believe the other side to be true. It is dangerous only if it is true.”

Conviction of the truth of Christianity should not lead us to ignore the historical arguments against it. Rather, conviction of the truth of our faith requires open investigation of the facts, on both sides. Our faith is a falsifiable faith.

Upon returning to the U.S., Machen became increasingly involved at Princeton Seminary, initially teaching Greek and later becoming a New Testament scholar. But he harbored the aspiration to return to Germany and to bring the rigors of its historical scholarship to Princeton Theological Seminary.

The Transformation of Princeton

This period, the turn of the 20th century, coincided with Princeton’s transformation from an institution deeply tied to Presbyterian theology to a modern research university. Woodrow Wilson was one of the theorists and architects of this change. Wilson, himself a Presbyterian, was not opposed to faith but insisted that it should not inhibit rigorous scholarship, including the historical study of the Bible.

Dr. Burnett reveals, through extensive analysis of Machen’s private letters, that he was firmly on the side of the “New Princeton.” He wanted Princeton, including the seminary, to level up its scholarship. In fact, Machen held rather a low view of Princeton Seminary’s academic standards. For example, he thought that B. B. Warfield was more “churchly” than rigorously academic.

When Princeton Univeristy hired a modernist New Testament scholar, Luke Miller, Machen thought it insufficient for the seminary to retreat to its old doctrinal formulations. He believed that conservative scholars needed to engage in the same rigorous historical research as their liberal counterparts to demonstrate the reliability of Scripture. Together with New Testament professor Dr. William Park Armstrong, Machen hoped he could contribute both to the improvement of Princeton Seminary’s scholarly reputation and to a sufficient historical and intellectual response to modern biblical criticism.

Machen’s Modernist Method — But Orthodox Theology

Machen’s adoption of modern critical methods was not merely a matter of course. Traditional, orthodox Christians often resisted both the conclusions and the methods of historical criticism.

Machen, however, distinguished between the two. He maintained orthodox Reformed theology yet believed that rigorous, objective scholarly methods could be employed to defend the faith.

He argued that rather than simply asserting that “the Bible says so,” conservative scholars should undertake historical research to show that the New Testament accounts are historically credible, thus grounding faith in objective evidence.

A Shift Toward Fundamentalism and Presuppositionalism

Over time, however, Machen became increasingly disillusioned with the hope that neutral, objective scholarship could vindicate Christianity. He began to see the liberal-conservative theological divide as not merely a difference in conclusions, but a divide rooted in entirely different presuppositions and worldviews.

This led to his famous book Christianity and Liberalism, where he argued that theological liberalism was, in fact, another religion altogether—a secularized version of Christianity devoid of supernatural claims.

Gradually, Machen shifted away from a purely evidential approach toward acknowledging that adopting supposedly neutral methods might already concede too much ground to secular presuppositions. For example, in a 1933 address to a convention held by the National Union of Christian Schools, Machen argued:

“The minute a professing Christian admits he can find neutral ground with non-Christians in the study of ‘religion’ in general, he has given up the battle.”

—from “The Necessity of the Christian School,” quoted in Burnett, 571

To adopt a neutral method or find intellectual common ground with unbelievers was already to concede the battle to unbelief.

Machen’s new perspectivalism anticipated the presuppositional apologetics of Cornelius Van Til, one of Machen’s hires at Westminster Seminary.

Machen’s Tragic End

Machen’s story is ultimately tragic. He became a hero fighting the rising tides of modernity, only to be forced out of both his denomination and seminary. He founded Westminster Theological Seminary and the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, but died within the decade on January 1, 1937, in his mid-50s.

Reading Burnett’s biography has prompted me to rethink many aspects of Machen’s life and thought. For example, in my other essays and videos at The Natural Theologian, I’ve explored presuppositionalism and how Van Til charted a new direction from Machen’s in the early decades of Westminster Seminary.

(The latter is the subject of a forthcoming interview — stay tuned!— with Dr. Keith Mathison, author of the book Toward a Reformed Apologetics: A Critique of the Thought of Cornelius Van Til.)

Yet, as I finished Machen’s biography, I realized that Machen himself shifted in the presuppositional direction. He had lost his original hope that purely objective scholarship could secure the faith.

Lessons for Today’s Christians

Four lessons for contemporary Christians emerge from Machen’s life and Burnett’s biography.

If you enjoy content like this, hit the “like” button and subscribe so I can write more essays like this and reach more people for the cause of natural theology and Christian humanism!

Want to make a one-time donation to The Natural Theologian instead of a recurring subscription? Tip the writer and make your contribution by “buying me a coffee.”