Toward a Sophisticated Realism

Sophistication does not come with the recognition of the role of conceptions, presuppositions, and frameworks in knowledge, but with an openness to the breadth of human experience of the world.

A year or so ago, I walked into a local coffee shop and noticed that the young man in front of me was carrying works of Heidegger and other philosophers under his arm. I engaged him in conversation, and our conversation over the next two hours reminded me why I needed to be a Christian voice in philosophy.

As it turned out, my conversation partner was a graduate of Calvin College, who had studied philosophy under James K. A. Smith. From Smith, among others, he had learned the Christian postmodernist line, that since Kant, we have all just known that you can’t directly experience the world. Therefore, Christianity cannot be the one truth about the world because objective knowledge is not possible. We cannot get objective truth because concepts come in between us and the world. These concepts are merely socially constructed and thus do not show us the objective world.

Under the influence of these ideas, my conversation partner had ceased himself to believe in Christianity over the course of several years during which he had been an admissions counselor to Calvin College, advertising a Christian education to its incoming students. In fact, this is how I had seen things go before. The philosophy professor on campus introduces the benighted evangelical kids to postmodernity, and they no longer believe that objectivity, knowledge, or truth are possible. They briefly adopt Christian postmodernism before lapsing into unbelief.

Having studied philosophy and Kant himself in some depth, I had reason to question some of the philosophical conclusions this man had come to in an undergraduate degree. He was basing his life on conclusions about philosophy he had been taught by someone else. There was a faux-sophistication in his dress, his way of speaking, and the confidence with which he spoke. In particular, he thought that realism - the idea that there is a reality that we can know - was a naïve view, naïve like the evangelical Christians from among whom he hailed, while his postmodernist view - that our minds cannot know the world because our socially constructed concepts get in the way - he took to be sophisticated.

My arguments were to no avail. The certainty with which he claimed that there was no such thing as certainty irked me, but my own rhetoric was powerless to overcome it. It is this kind of conversation that I have in mind as I discuss realism here.

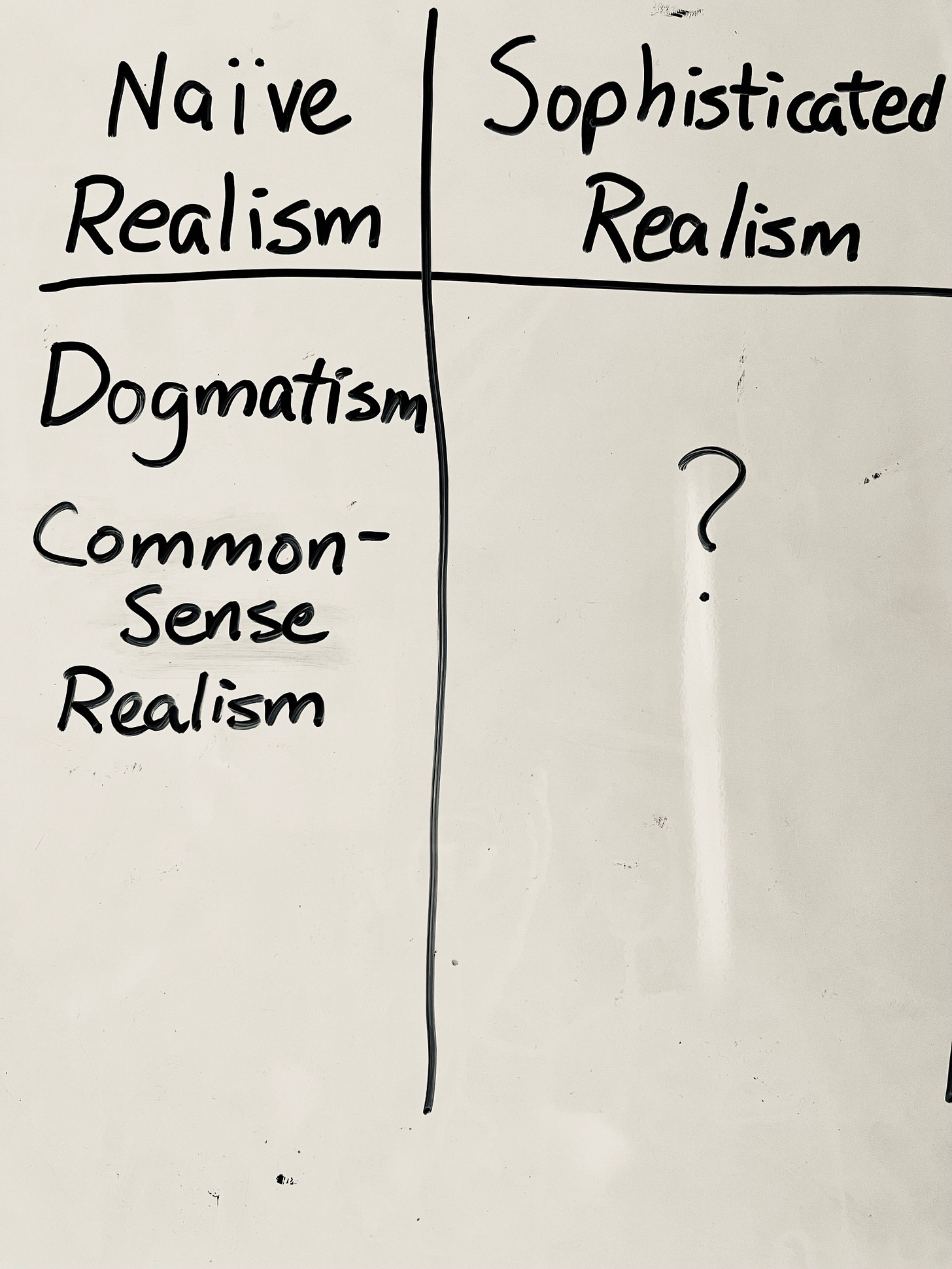

Naïve Realism?

My discussions of realism began as I, in this post, laid out the argument of my dissertation, that the objects of human thought are not our own concepts but the real objects of the world. I called this view Christian direct realism. A reader responded by recommending what he called the critical realist view, that we know the real world but mediated by our own concepts and frameworks, which may be due to our social conditions.

I think I may have given the wrong impression by arguing for “direct realism,” which sounds approximately like “uncritical” or “naïve realism.” (The Stanford Encyclopedia calls direct realism “naïve realism.”) On the contrary, I have viewed my reflections on knowledge as attempting to achieve sophistication but in a particular way.

There is indeed a kind of realism that is uncritical or naïve and, I would add, dogmatic. This kind of realism assumes that it is already correct without further levels of critical examination and sophistication.

Here’s an example: Against third-wave feminism, a Christian guy asserts that the biblical teaching is that the man should work outside the home to provide for his family and a woman should do home-making. He cites a couple of choice verses, and it seems to him like mere disobedience to do otherwise. He believes that biblical revelation tells us the real moral obligations we are under and the structure of the universe. He is a realist: It is not just his subjective, religious perspective that the division of labor among the sexes should be organized a certain way, but a divine command.

However, examination of the history of household economy reveals that this stark division of labor has been quite rare in history, being noticeable in Victorian England and 1950s America, while elsewhere households have taken on many different divisions of labor, often with different tasks for man and wife, but not as stark as the 1950s division of labor would suggest. As this Christian is an American evangelical, whose grandparents were raising children in the 1950s, this era appears to be a golden age of morality, hence, he has imbibed the assumption that this is what God commanded.

In this example, there is a clear movement from naïveté to a more critical perspective. So long as the revelation of social conditions shaping one’s thinking and biblical interpretation does not destabilize belief altogether, this would lead to a “critical” realism.

But in my experience, this revelation often does destabilize belief. If this belief turned out to be socially conditioned, how many of my other beliefs are? Is it even possible to hear the voice of God in Scripture if we always interpret it through our own cultural lenses? This is a form of skepticism. The very class of things introduced to bring sophistication as mediating reality to us, socially-inherited conceptions, worldviews, frameworks, etc., now seem to obscure it altogether.

Now, here is my more sophisticated objection to critical realism: If sophistication is supposed to lie in the recognition of how our conceptions and presuppositions interpret reality to us, then the skeptic and the critical realist are equally sophisticated, and there is no clear reason in the philosophical position itself to avoid the skeptical view.

Even among the dogmatists, like the Reformed presuppositionalists at Westminster Seminary, it is the recognition of the mediating role of worldviews, conceptions, and presuppositions that is taken to provide sophistication. Accordingly, evidentialist apologists are taken to be singularly naïve, and presuppositionalism to be a source of sophistication. “We presuppositionalists wisely recognize the role presuppositions play in knowledge. You can only get to Christian conclusions from Christian premises. Knowledge comes by deduction from the original-language propositions of the biblical autographs. Thus, we would never argue with an unbeliever on common ground or objective evidence. In fact, we don’t think that there are any shareable, common human, objective methods of knowledge-acquisition.” Note: With biblical dogmatism comes utter skepticism about all common human knowledge.

This is why I do not think that the step of recognizing the role that presuppositions, social conditions, human conceptions, and so on play in knowledge is the step at which a sophisticated epistemology is reached, certainly not a sophisticated realism. This may be one moment in the path toward knowledge, but it is actually a negative moment and a skeptical one. We recognize our original epistemic position as not the knowledge we thought it was, but as a complex form of ignorance. This is a necessary step in the acquisition of knowledge, but it is not itself the attaining of knowledge, but the recognition of ignorance. It is also not the linchpin of realism but of skepticism (even if a skeptical moment turns out to be a necessary moment in the development of knowledge).

However, the recognition that we could be wrong is essential to realism. What is realism, after all? It is certainly not the idea that whatever I currently think is certainly correct. That is a form of dogmatism. Realism is ultimately the idea that there is a reality to which our thought is accountable. There is a standard by which my thoughts can and should be judged, and it comes from outside me, from the reality which is the object of my thought and the criterion by which its accuracy must be judged. This means that the possibility of error is essential to realism. Recognition of the possibility of error need not lead to skepticism. Instead, error is possible because there is a reality to which our thought is accountable.

This means that skepticism itself actually breaks down. Skepticism notices that I could be wrong about any particular thing that I think. But then it calls into question the very possibility of knowledge and of the existence of a reality external to thinking itself. But if this were so, then none of my thinking could be said to be so much as wrong. And then skepticism could never get started.

On the contrary, realism is compatible with doubt about many (if not every) particular belief I have. To doubt our beliefs is to acknowledge that reality is external to our beliefs and so could prove to be otherwise than we thought it was. In short, the possibility of error does not lead to the impossibility of knowledge; rather, the possibility of error is an indication that there is such a thing as reality which, if we could apprehend it, would give us knowledge.

Objective Experience

The real question is now, do we have any method of apprehending this reality that is external to our beliefs? And the answer is, yes, experience. In the traditional philosophical division of intellectual faculties, the mind has the faculties of reason and experience. Reason can check for the coherence of existing beliefs by the application of logical canons and can deduce logical conclusions from given premises. But this requires experience in order for there to be such beliefs and premises.

Now, various kinds of rationalism argue that reason alone can provide us with at least some beliefs and premises. While rationalism is a common position in the history of thought, I think it can be passed over relatively quickly in this discussion, because reason does not seem like the best candidate to put us in touch with a reality distinct from our own minds and beliefs. While many analytic philosophers, for example, will argue that reason alone puts us in touch with such abstract entities as numbers, sets, and possible worlds, by a kind of intellectual intuition, this position will make little sense outside of analytic philosophy. Experience is the primary candidate for putting us in touch with a reality beyond our heads.

But the main objection to treating experience as a source of knowledge of reality is a renewed skepticism that says that experience is subjective. It tells us about something that is going on with us but not with the world. In its most extreme form, Cartesian skepticism and Berkeleyan idealism suggest that our experience does not acquaint us with the objects of the world, but only with a veil of ideas, subjective representations which are entirely compatible with the non-existence of the objects they purport to represent. More popularly, we encounter the idea that experience is subjective and does not tell us about the objective world but about the meaning-making dimensions of ourselves.

When experience is treated as subjective, people commonly treat it as therefore unquestionable. In one way, this makes sense; given that it is subjective and does not even purport to represent the objective world as being a certain way, there is no standard or criterion by which it could be evaluated negatively. On the other hand, when people speak of “my truth” and “your truth,” treating experience as making truth-claims that are simply not subject to evaluation, they are being inconsistent. If experience is reductively subjective, then it doesn’t even represent “my truth” or “your truth.” It just says something about me or you. It says nothing about how the world is, not even how “my world” or “your world” is.

When people adopt this subjectivist way of thinking, they often insist on hearing and respecting other people’s “subjective experiences.” But one wonders why. If what is true for them may not be true for me, why bother learning what other people subjectively project things to look like? I believe there is a lingering recognition of an alternative objective structure to experience. One reason to recognize the subjectivity of experience is to recognize the limitations of any of our vantage points on the world. Given the way I am shaped, the concepts and frameworks that I bring to experience, I will see certain things and not others. I want to learn from others because they see the world from a different vantage point and have information and perspective that I lack. As I hear from them what the world looks like from their vantage points, I update and expand my map of the world. In other words, the experience of individuals is important because it provides information about the objective world.

The subjectivity of experience can be accounted for in something like the way of physical position. If I am physically positioned in a certain location, I can see some things and not others. By speaking to other people who are otherwise positioned, I can gain information about the layout of things without having to be in each position. And in the realm of life experience, unlike physical position, it is not even possible to inhabit each location. Each person has unique experiences and information to which I cannot have direct access, not because experience is reductively subjective and unquestionable, but because experience is situated in a world in which we each inhabit a particular position that cannot be completely replicated or experienced by another.

How do we achieve sophistication, then, in our realism and in our methods of knowing the world? Once again, I do not believe that sophistication comes in recognizing the role of concepts, worldviews, etc. in knowledge. Rather, I believe that sophistication comes with an openness to the breadth of experience, both broad human experience (not just my own experience) and systematic experiential knowledge (including modern science), as opposed to unsystematic observation. The recognition of concepts, social conditions, etc. as shaping our knowledge can indicate to us that our own individual experience will not suffice and that experiential knowledge that is unsystematic and lacking verification and correction for cognitive biases will also be insufficient. Instead, we need means of expanding the range and quality of experiential knowledge available to us. That is sophistication.

How would sophisticated Christian realism play out in the example above? The Christian who realizes that the 1950s have shaped his expectations and not the Bible alone can open himself up to further biblical knowledge, further historical knowledge, further philosophical reflection, further empirical knowledge about the sexes, and the wisdom of the men and women around him who have navigated this before. Biblically, he might reread Proverbs 31, noting the significant economic productivity and autonomy of the wife. Historically, he might learn about the significant sociological changes between societies in which wives did not own property and those in which a husband and wife are both owners of their joint assets. Philosophically, he might learn about the idea of the productive household, the way in which the household itself has been at times understood as the unit of productivity, with husband and wife and even children each playing a role in economic production. Empirically, he might recognize the psychological distinctions in the bell curves of personality across the sexes, as well as the significant overlap between male and female personalities; he may recognize that psychological differences account for much of the division of labor across time and place, but that there are variations and exceptions. Finally, he may learn from the experience of Christian couples he meets and see the variations in how they handle the division of labor in and outside the home. At the end of this, he will have neither a strict, biblical division of labor nor an idea that it is all socially constructed and anything goes. Rather, prudence will reign, the difference between the sexes will be acknowledged, and significant freedom in how their differences play out will be allowed. God did say certain things in the Bible, but he also made us and our natures, and attention to nature and history is essential.

Sophistication, True and Merely Apparent

In the West, Bible-believing Christianity has gained the reputation of a lack of sophistication. In a way, all my own studies and those of other evangelical intellectuals are an attempt to achieve some of that sophistication, whether it will ever be recognized as such or not. But in my experience, there is a shortcut to the appearance of sophistication, and it is the adoption of a postmodernist and implicitly skeptical line of thought. Some people manage to adopt this posture while retaining living personal faith, but as often as not, it leads people to doubt God and to doubt the claims of Christianity.

Nevertheless, sophistication is not optional, at least for those of us cursed with the desire for knowledge, with which comes much vexation. As a Christian, I cannot help but want to see that, however foolish the world thinks us, it is not foolish to believe and follow Christ.

In my own academic studies, I have come to the conclusion that postmodernism is not the path to sophistication, as is proposed in many (even Christian) college humanities departments; nor presuppositionalism, as at Reformed seminaries like Westminster; nor the methods of analytic philosophy, as in some of the Christian philosophy departments I have encountered. Rather, sophistication comes with openness to the breadth of human experience and knowledge, a (not exclusively) Christian empiricism and humanism, of the kind I was offered at the University of Chicago, the one non-Christian institution I attended. As I have mentioned before, engraved in stone above the reading room there, is the following quote from Francis Bacon, which sums up this approach to reading and knowledge: “Read, neither to believe nor to contradict, but to weigh and consider.” This posture of humble openness to the breadth of human experience is what I recommend and what I consider to be the mark of true, and not merely apparent, sophistication.

A great read, and I really appreciated this: 'If experience is reductively subjective, then it doesn’t even represent “my truth” or “your truth.” It just says something about me or you. It says nothing about how the world is, not even how “my world” or “your world” is.' Exactly: the statement "it's subjective" seems to suggest a deconstruction of something, and yet that only follows if the statement says something "true." That, or the statement "it's subjective" suggests something which cannot be challenged, but it's meaning requires others to acknowledge and understand. Anyway, the article was very rich, and I also really liked: 'Rather, sophistication comes with openness to the breadth of human experience and knowledge, a (not exclusively) Christian empiricism and humanism' - I completely agree.