Tim Keller and Kevin DeYoung Miss the Nature of Sexual Desire

Keller and DeYoung are unable to acknowledge that any dimension of desire is part of human nature; this leads them to unbiblical positions both to the right and the left of the Bible.

In the last several weeks, I have been thinking a lot about the question of what the Christian life looks like for those with a same-sex sexual orientation.

TJ Espinoza and David Frank recently interviewed me for their podcast “Communion and Shalom” on the subjects of theology and same-sex sexual orientation, and I will be excited to share that interview with all of you when they publish it. We talked about what it means to be a “natural theologian,” how theology can be open to experience, and why I agree with Side B that same-sex sexual orientation exists and should not be condemned, in spite of my generally more theologically conservative perspective.

My friend’s PCA church (Presbyterian Church in America, the theologically conservative denomination of which I am also a member) also recently started a Sunday school on the report of the PCA’s Ad Interim Committee on Human Sexuality. That has sparked two lengthy Sunday afternoon discussions.

Then, this morning I listened to Tim Keller and Kevin DeYoung discuss the committee report, to which they both contributed as committee members. I was surprised by what I heard. The errors I feared would come from failing to understand the nature of same-sex sexual orientation they indeed made and made explicitly, chiefly, these three:

There is no dimension of desire, particularly the capacity for and disposition to desire, that is merely natural and not sinful.

Sexual holiness for heterosexuals would involve ceasing to have an attraction to members of the opposite sex generally but only to one’s spouse.

Jesus was tempted in a merely passive sense and experienced no desire or passion in being tempted.

1. Sinful Desire and Natural Desire

To begin with, Keller and DeYoung were unable to acknowledge that any dimension of desire was part of human nature and not itself sinful. This extends even to the disposition or capacity to experience sinful desire, as Keller says: “The capacity for sin is still wrong; it’s original sin” (DeYoung and Keller Discuss Report on Human Sexuality, 28:57). In context, they are discussing heterosexual sexual temptation, on which more below, but the point is general: Our capacity for sinful desire is itself sinful.

On the contrary, our capacity for desire is natural and not inherently sinful, and many of the desires we experience should be seen as emblematic of our nature. For example, if we brought up the mere desire for food, Keller and DeYoung would acknowledge that that is a natural desire. It only becomes sinful under certain conditions.

But there is no way to separate natural desires from sinful desires. My desire for a hamburger is natural, but under certain conditions, the very same desire would also be sinful. The disposition and capacity for such desires is part of human nature, even though in postlapsarian conditions, this capacity also gives rise to sin.

Because of this oversight, Keller and DeYoung imply a sort of hypothetical perfectionism as the goal of temporal sanctification, to quote them, “The goal is not just consistent fleeing-from and regular resistance to temptation but the diminishment and even the end of the occurrence of sinful desires, through the reordering of the loves of one’s heart toward Christ.” This is an error that departs from a Reformed account of sanctification. Growing in holiness involves, in essence, growing in the ability to obey God and resist temptation, not in ceasing to be tempted. Undoubtedly, there are changes in our affections and desires as we are sanctified, but the cessation of temptation or “sinful desire” promises an incorrect perfectionism.

2. Is Opposite-Sex Attraction Sin?

The committee report encourages same-sex attracted Christians to seek to repent of their being same-sex attracted. But by the same token, Keller and DeYoung end up condemning people who have an opposite-sex sexual orientation for having this orientation as well.

One response to this is “Good, we should condemn all sin equally.” But the problem is that what has been condemned as sin is not sin: The biologically normal result of puberty is not itself original sin.

Here is what Keller says:

“If I was perfectly sanctified, I would have no ability to even sexually desire a woman other than my spouse. But the fact is, because we’re not perfectly sanctified, all heterosexual men who are married have that ability to desire that, and that is illicit.” (28:22)

On this account, sexual holiness would involve only experiencing sexual desire for one’s spouse, not for other members of the opposite sex. Two things are conflated here - the Christian’s duty with regard to the 7th commandment, and a realistic psychology of sexual holiness. Our duty per the 7th commandment is not even to lust for a person other than our spouse. But the fact that someone experiences sexual desires for the opposite sex generally is not as such sinful. That is the natural result of the biologically normal puberty, resulting in what we might call a heterosexual sexual orientation. We cannot condemn that.

It is true that some same-sex attracted individuals who nevertheless marry someone of the opposite sex (in a so-called “mixed-orientation marriage”) report an attraction to their spouse as a member of the opposite sex exclusively. Perhaps, some purportedly asexual individual somewhere could muster up erotic affection for one person of the opposite sex, but otherwise, we have no evidence that such a pattern of desire is even psychologically possible, much less ethically obligatory.

On the contrary, I would hypothesize that in the ordinary case, sexual desire for one’s opposite-sex spouse is an instance of one’s general susceptibility to opposite-sex sexual desire. In fact, this is what it means to desire someone sexually; it means to desire them as a member of the general sex, not interchangeably with every person of the opposite sex, but as a member of the sex to which one is generally attracted. This means that the hypothetical holiest individual does not have to be someone who is literally only attracted to his or her spouse. He does need to restrict his sexual imagination, lust, and of course, behavior, but he does not need, nor should he seek, to cease to be heterosexual.

3. Was Jesus Really Tempted?

When it comes to Christ himself, because of their strict doctrine of the sinfulness of desire, Keller and DeYoung are unable to articulate how it was that Jesus was tempted as we are. In what sense was Jesus tempted “in every way, as we are?”

Of Christ, the committee report says, “Christ experienced temptation passively in the form of trials and the devil’s entreaties, not actively in the form of disordered desires” (Statement 8 of the report). This statement depends on an attempt earlier in the report to distinguish between the temptation to which Christ was subject and the temptation to which we are subject by distinguishing temptation that arises from within and from without (Statement 6). Temptation from within is sinful desire; temptation from without comes in the form of trials and suffering. According to the report:

We affirm that Scripture speaks of temptation in different ways. There are some temptations God gives us in the form of morally neutral trials, and other temptations God never gives us because they arise from within as morally illicit desires (James 1:2, 13-14). When temptations come from without, the temptation itself is not sin, unless we enter into the temptation. But when the temptation arises from within, it is our own act and is rightly called sin.

This is bad theology. There are “temptations God never gives us because they arise from within as morally illicit desires”? So God only tempts us in ways that do not involve us actually being…tempted?

For Jesus, if he heard Satan’s entreaties (a “morally neutral trial”) and experienced no desire for what Satan offered, was he really tempted? If Jesus’ temptation did not involve any desires on his part, then Jesus was not tempted. The idea that he took on our nature, suffered as we suffer, was tempted as we are tempted ceases to have any real effect. The logical conclusion of such a position would be that Jesus lacked a human nature, the classical heresy of Monophysitism, that Jesus was only divine and not human.

Once again, we must recognize a dimension of desire or at least the capacity for desire that is natural and not thereby sinful. Jesus, to be tempted, must have been subject to some desires, which if he followed them could have led to sinful ends.

Christ Against Nature

In light of this, I have a growing sense that the debate concerning so-called “same-sex attraction” in evangelical churches is reflective of broader difficulties in Christian theology. The view that nature itself is evil and that Christ couldn’t really have adopted our nature is lurking in the background. Richard Niebuhr would call this “Christ Against Culture,” but in this case, it’s Christ Against Nature.

Stereotypically, the “Christ Against Nature” position is seen in a fundamentalist and puritanical suspicion of the body itself. Christians who view all pleasure, fun, and enjoyment as indicative of sin exemplify this stereotype. Keller and DeYoung are not of this variety, but the same pattern of thought arises when they discuss sexual desires.

The “Christ Against Nature” position also crosses political aisles in the following way. Right after arguing that opposite-sex sexual desires are illicit, Keller says, “We have to be very careful not to say, “To desire a man is unnatural; to desire a woman is natural” (28:42). Compare the apostle Paul:

For this reason God gave them up to dishonorable passions. For their women exchanged natural relations for those that are contrary to nature; and the men likewise gave up natural relations with women and were consumed with passion for one another, men committing shameless acts with men and receiving in themselves the due penalty for their error. (Romans 1:26-27 ESV).

The denial of nature pushes Keller and DeYoung to unbiblical positions both to the right and the left of the Bible.

This may be confusing: I am saying on the one hand that the affirmation of nature includes recognizing same-sex sexual orientation and desires as something naturally occurring, and on the other, saying that we should affirm that heterosexual sexual relations, orientation, and desires are natural while their homosexual counterparts are unnatural.

But this is exactly what the affirmation of nature amounts to. It is not the affirmation merely of “creation,” a word theological conservatives have urged me to use rather than “nature.” Keller and DeYoung affirm that, before the fall, the creation was good, and to the extent that that nature persists, it is good. But that is not enough.

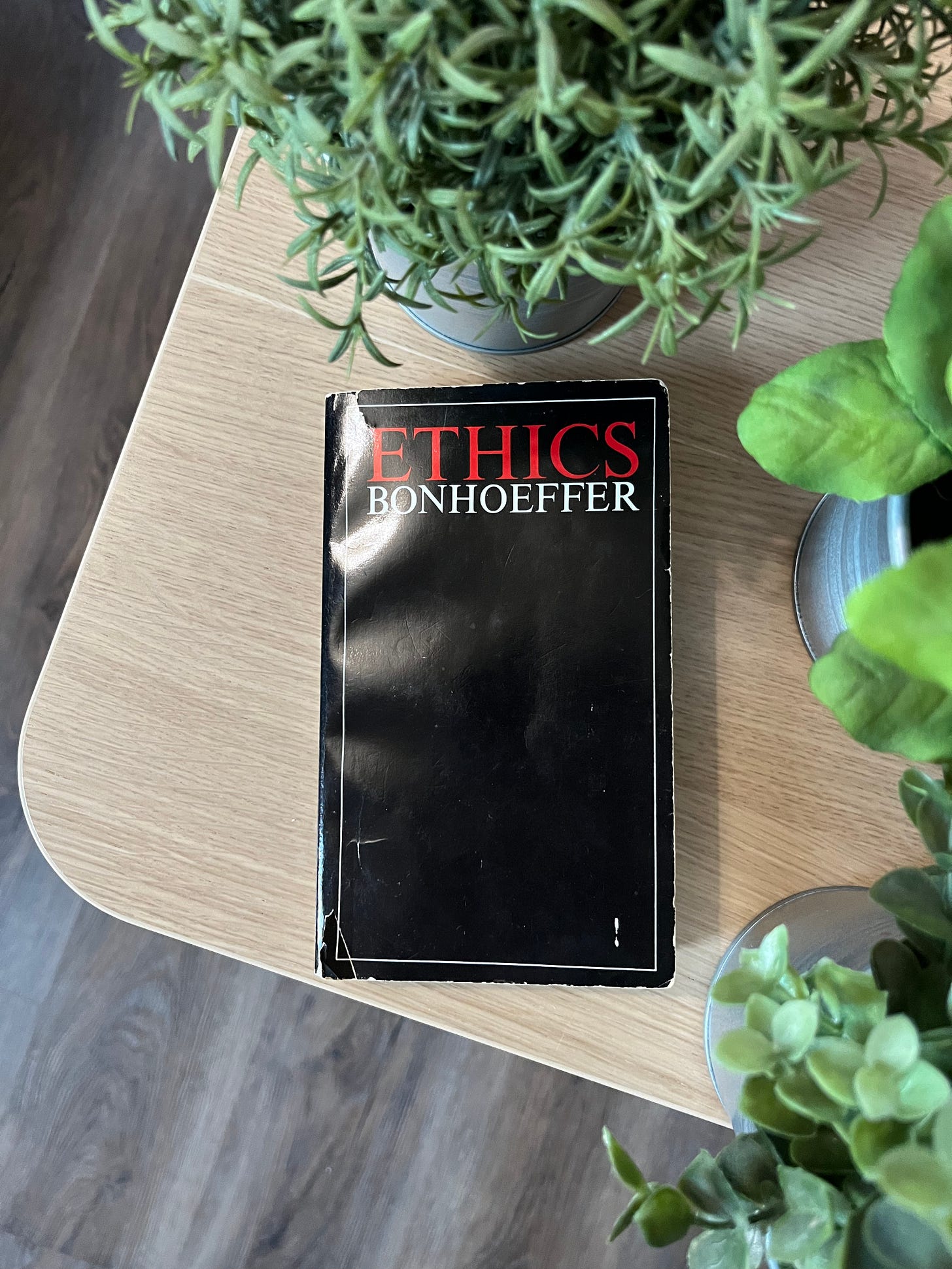

Dietrich Bonhoeffer explains what happens when Protestantism loses the category of nature. The category of nature describes the world as it is in its postlapsarian state, the combination of created nature and fallen nature, in unity and tension. A mere affirmation of “creation” suggests that in some hypothetical state long ago the world was good, but “nature,” the stuff around us right now, this stuff is gross and corrupt, sinful nature.

But the world is more complex than a neat division between prelapsarian creation and postlapsarian corruption suggests. Our nature includes a whole complex of motivations that are given to us. Some of them are more broken from the fall, some less. They reflect the sin of our condition, but also its misery. The nature of a same-sex attracted individual is no less natural in this sense because it is unnatural with respect to the ideal of prelapsarian creation. For even the desires that can lead us to sin are reflective of our created origin, of the good purpose for which God created us.

Both same-sex and opposite-sex sexual desires can lead us to sin, but both are, though differently, reflective of a combination of the good purposes for which God created us and the fallen purposes that we would pursue. The Christian hope is that our nature, even our nature could be saved, because our nature was assumed by the second person of the Trinity. This is why the Christian response to same-sex sexually oriented individuals is so important. Do we think God can save people whose nature includes that? If we answer “No,” how do we think God can save any of us?

Same-Sex Attraction and the Misery of Our Condition

My fellow theological conservatives commonly hold that the “Side B,” celibate gay Christian position does not have scripture and the confessions on its side. Side B’s use of the word “gay” is thought to make too many concessions to the cultural and political movement that would transform sexual relationships across Western countries. Specifically, it is…