Praeparatio Evangelica: The Evangelistic Step Evangelicals Forgot

Lessons from the Church Fathers Justin Martyr, Clement of Alexandria, and Eusebius of Caesarea

[Doorbell buzzes]

“Hello! Would you like to change religions? I have a free book written by DJEE-ZUS!”

While the Broadway show from which that line comes is not about evangelicals but Latter-Day Saints, it fits.

The average evangelical is liable to think that their free afternoons and weekends ought to be spent engaged in similarly abrupt evangelistic conversations.

After all, people are dying! If we don’t act quickly, they’ll soon face God’s throne of judgment; and then they’ll go to hell.

But our Christian forefathers would have had us behave with more circumspection and preparation. Since the second century, Christian theologians have recognized the reality and even necessity of what Francis Schaeffer called pre-evangelism. The Church Fathers called it praeparatio evangelica, preparation for the gospel.

But since the 19th century, American Christianity has been shaped more by tent revivals than patristic treatises. We have cultivated an urgency to share the gospel as soon as possible, to drive the unbeliever toward conversion, to immanentize the personal eschaton.

Theological theories have sometimes reinforced this. Cornelius Van Til criticized Francis Schaeffer for holding that there was a work of pre-evangelism prior to the acceptance of a Christian worldview. This was to concede too much to autonomous man and his felt need of proof or persuasion.

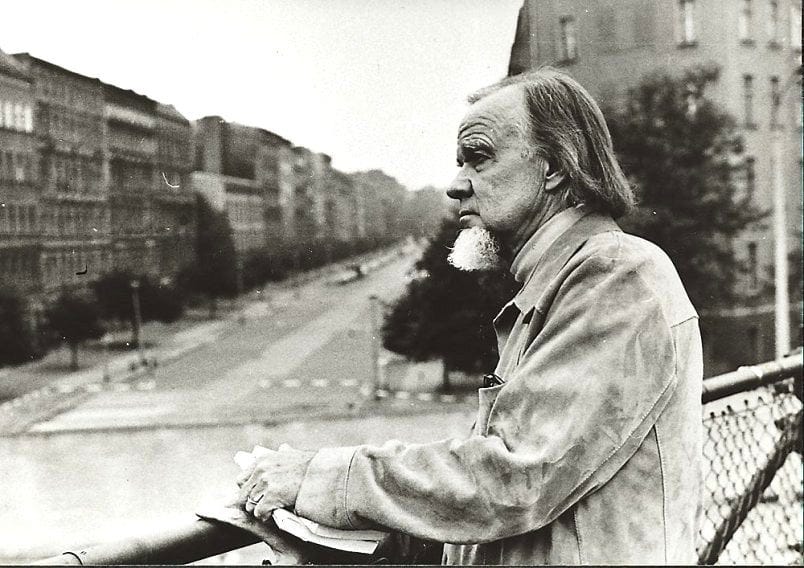

However, in the absence of Christian pre-evangelists, God gave us a non-Christian one. Theaters fill to hear Jordan Peterson lecture about the Bible. Secular podcast hosts press him on his Christology. And just as the wokeness Peterson opposed was experiencing defeat in last year’s election, the long ebb of the sea of faith began to reverse.

Rather than asking whether Peterson is a Christian, we should understand Peterson’s work as a praeparatio evangelica. In doing so, we join a long tradition of Christians who hold that non-Christian philosophers can and do prepare the way of the Lord.

This Just In: Justin Martyr Finds Seeds of the Word Among the Greeks

Justin Martyr (c. 100 – c. 165 AD) was a Gentile and a pagan who took up the study of philosophy in pursuit of truth and spiritual guidance. He found himself dissatisfied first with his Stoic tutors, then with a Peripatetic philosopher, and then the Pythagoreans. He adopted Platonism as a result of this search.

But, encountering a Syrian Christian while walking on the beach, the old man told him of the ancient prophets and “spoke of the testimony of the prophets as being more reliable than the reasoning of philosophers.” Justin was converted. He came to regard Christianity as “the true philosophy.”

However, Justin did not therefore conclude that all he had learned before was for nought, that all the rest of philosophy was falsehood. Rather, he concluded that the transcendent God in whom he had believed as a Platonist was the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. The God who was the very form of goodness was he who had taken on the form of a man.

In his First Apology, Justin wrote that the philosophers before Christ had happened upon seeds of the Word, logos spermatikos, which led them along a path whose fruition was Christ himself.

Justin concluded that many before Christ who had followed these seeds of the Word, living in accord with God’s Logos, were proto-Christians: “Those who have lived reasonably are Christians, even though they have been thought atheists.”

Justin speculated that Plato may have had access to the writings of Moses. And he lauded Socrates as a martyr pre-figuring Christ.

Rather than becoming an evangelist, Justin dressed as a philosopher. Like Plato, Aristotle, Epictetus and others before him, Justin founded a school of philosophy. While he believed that Christianity was the true philosophy, he led others toward its truth by instructing them to detect the logos spermatikos in the great philosophers before Christ.

Justin was first in a long line of Christian theologians recognizing philosophy and secular wisdom as preparation for the gospel.

What the Old Testament was to the Hebrews: Clement of Alexandria on Greek Philosophy

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 215 AD) was, like Justin before him, a convert to the faith. Born a pagan, he rejected paganism “for its perceived moral corruption.” He traveled across Greece, searching for religious training, eventually studying Christian doctrine at the Catechetical School of Alexandria.

In his writings, Clement rejected the Greek mystery religions of his upbringing. But in his Stromata, Clement argued just as fervently for the preparatory value of Greek philosophy. Philosophy was for the Greeks what the Law had been for the Hebrews, argued Clement. It was a propaedeutic, or “schoolmaster to bring the Hellenic mind to Christ” (See Gal. 3:24).

Clement described the benefit of philosophy both before and after the advent of Christ:

“Before the advent of the Lord, philosophy was necessary to the Greeks for righteousness. And now it becomes conducive to piety; being a kind of preparatory training to those who attain to faith through demonstration. … For God is the cause of all good things; but of some primarily, as of the Old and the New Testament; and of others by consequence, as philosophy. Perchance, too, philosophy was given to the Greeks directly and primarily, till the Lord should call the Greeks. For this was a schoolmaster to bring the Hellenic mind, as the law, the Hebrews, to Christ. Philosophy, therefore, was a preparation, paving the way for him who is perfected in Christ.” (Clement, Stromata, Book 1, Chap. 5)

Christian critics of philosophy fear that we will study it uncritically, or hail one figure as having the whole truth. But Clement denied that Christian appreciation of philosophy should be either uncritical or partisan:

“The Greek preparatory culture, therefore, with philosophy itself, is shown to have come down from God to men, not with a definite direction but in the way in which showers fall down on the good land, and on the dunghill, and on the houses.…And philosophy — I do not mean the Stoic, or the Platonic, or the Epicurean, or the Aristotelian, but whatever has been well said by each of those sects, which teach righteousness along with a science pervaded by piety — this eclectic whole I call philosophy.” Sophistry is dangerous, not philosophy.” (Stromata, Book 1, Chap. 7)

The Christian approach to philosophy should be critical and eclectic.

Clement also criticized the folly of Christians denigrating philosophical study for bare faith:

“Some, who think themselves naturally gifted, do not wish to touch either philosophy or logic; nay more, they do not wish to learn natural science. They demand bare faith alone, as if they wished, without bestowing any care on the vine, straightway to gather clusters from the first. … So also here, I call him truly learned who brings everything to bear on the truth; so that, from geometry, and music, and grammar, and philosophy itself, culling what is useful, he guards the faith against assault.” (Stromata, Book 1, Chap. 9)

The Christian thinker and apologist must prune the vine and till the soil, rather than trying to gather the harvest immediately and without sufficient preparation.

Contemporary Christians need to hear Clement’s exhortation for preparation for the gospel.

Eusebius: Van Til of the Fourth Century?

The phrase praeparatio evangelica, however, is best known as the title of a work by the 4th century theologian Eusebius (c. 260/265 – 339 AD). In Praeparatio Evangelica, Eusebius actually disputed the idea that Greek philosophy was a preparation for the gospel. In fact, he argued that it was Hebrew wisdom and Scripture that was a preparation for Greek philosophy.

Now, Justin had, of course, toyed with the same idea, suggesting that Socrates had taken a page from Moses. Yet even Eusebius’ counter-argument was only necessary on account of the Church Fathers’ shared sense that Greek philosophy contained truths whose source could only be the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

In Eusebius, I detect more than a hint of Van Til’s 20th century claim that non-Christian thinkers operate, at best, on “borrowed capital.” But, if the evidence for Socrates’ and Plato’s access to Moses is slim, the evidence that all non-Christian thinkers operate only on borrowed capital — rather than the light of nature or the seeds of the Logos — is even slimmer.

The Necessity of Pre-Evangelism

Over Van Til’s protests, Francis Schaeffer urged the necessity of pre-evangelism. He argued that the first things the unbeliever needs to comprehend are the truths already displayed in reality itself:

The truth that we let in first is not a dogmatic statement of the truth of the Scriptures, but the truth of the external world and the truth of what man himself is. This is what shows him his need. The Scriptures then show him the real nature of his lostness and the answer to it. This, I am convinced, is the true order for our apologetics in the second half of the twentieth century for people living under the line of despair.

— Francis Schaeffer, The God Who Is There.

While Schaeffer argued for this method from his contemporary intellectual situation, he had the support of Justin and Clement from a very different time. We, in turn, are in yet another cultural and intellectual moment, yet the necessity of pre-evangelism remains.

In Schaeffer’s time, a confident logical positivism was ascendant in certain quarters. Yet simultaneously, existentialist philosophers pointed to the meaningless of a reductively material philosophy. At that time, the Christian apologist, perhaps, had an obligation to direct unbelievers from positivism to existentialism.

In recent times, New Atheism was ascendant; and yet, following the division of the atheist movement over social justice ideology, Jordan Peterson and the Intellectual Dark Web stepped in to explain the inevitability of religious and ideological thought. On this basis, Peterson urged us to find a deeper ground for our psyche than shifting ideological winds. He directed the Western world to an archetypal and psychological reading of the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures.

Today, Bible sales are up, and religiosity is on the rise. Ross Douthat, after sixteen years in the New York Times opinion pages, is simply saying it outright: Belief is the proper attitude for an intellectual. (His book Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious came out today.)

But the work of Peterson and others as a praeparatio evangelica does not absolve us of the same duty. In our conversations with those at and outside the boundary of faith, it is not our only work to harvest the fruit. We must first till the soil, water the seedling, and prune the vine. If God wills, we may have the opportunity of planting a seed or, even, of harvesting the fruit.

We are often too impatient to do so. But our Lord is not.

“He is not slow as some count slowness, but is patient toward you, not wishing that any should perish, but that all should reach repentance” (2 Pet 3:9).

If God is patient, then we can be too.

Share the gospel when the time is right, but before then and always, be preparing the way of the Lord.

Further Reading

Read

’s contribution on Christ as the master soil-tiller, which served as the foundation for our podcast conversation, “Don’t Share the Gospel…Yet.”And read my and Anna’s take on Jordan Peterson after attending the We Who Wrestle with God Tour:

Jordan Peterson: He Who Wrestles With God

The evangelical takes on Jordan Peterson’s “We Who Wrestle With God” tour are coming out. Jake Meador attended Peterson’s lecture in Omaha and says that Peterson’s ideology is focused on excellence to the exclusion of mercy. Aaron Renn attended in Indianapolis and