Our Unnatural Nature: On Homosexual Orientation

The category of “sexual orientation” has arisen by scientific observation of fallen, broken nature. And it is nature, in its unnatural condition, that must be incorporated into Christian theology.

I find that there are at least two dimensions of personal growth or, for Christians, progressive sanctification. The first dimension involves believing you can change, doing difficult things, and attempting to reshape ones habits and even inclinations. But the other dimension involves growing in self-understanding, accepting ones personality and nature, and deciding to live and flourish within those limits.

If there is an overemphasis in conservative Christian circles, the over-emphasis is on discipline, Stoicism, and the malleability of our personalities. Undoubtedly, this is a reaction to cultural trends like self-care and accepting ourselves for exactly who we are now. But ignoring our personalities, our limitations, our nature can have deleterious effects.

(I highly recommend reading about the Orthodox Jewish version of these two dimensions, in “What’s Chizuk?” by Shmuel Chaim Naiman, “The Healthy Jew.”)

Those of you who hold that gay Christians should confess their orientation and attraction as sin, I challenge you to consider whether you’re not ignoring the real limitations that our natures and personalities place on all of us in the process of Christian growth.

1. Same-Sex Attraction: An Ongoing Discussion

Earlier this week, I wrote about the way that, not only same-sex attraction, but even original sin sits at the boundary between sin and the misery that Christianity teaches is the result of the fall. This was in response to a discussion of my own arguments to that effect by Misty Irons and the hosts of Communion and Shalom.

At the same time, I find myself in ongoing conversations with friends on Twitter and at church, Bethel McGrew and Mason Bruza, who find my take too accommodating to contemporary sexual ideology. Mason, in this Twitter exchange, appealed to the importance of nature to argue that we should more clearly designate homosexuality as unnatural, rather than accepting that same-sex attraction can be part of unchangeable human nature. I appreciate Mason’s appeal to nature because I think it moves beyond facile quoting of Bible verses, on which we all agree. (That’s what James White did here, and Jared Moore undoubtedly will here.) The question of same-sex attraction is one where a biblical response must include reflection on the actual observation of human nature and the fact of unchosen homosexual orientation and attraction.

2. On Language, Contemporary and Antiquated

In our exchange, Mason brought up the modernity of the language of “sexual orientation” and also argued that “concupiscence,” a term for desire and sometimes sinful desire, is the traditional vocabulary for the same thing. But, given that the Reformed held that concupiscence was sin against the Catholic denial, my view would be a departure from the Reformed position.

In my post “On Being a Natural Theologian,” I included a brief section called “A Natural Style,” in which I argued that part of being a natural theologian was avoiding technical jargon and speaking in ordinary English. In spite of my own penchant for Scholastic theology, I think that is wrong to treat scholastic terminology, no longer in common use, as adequate to our contemporary theological tasks. Until you’ve said what you have to say in modern English, you haven’t really said it. We know what words seventeenth-century Reformed divines would use; but what is the contemporary way to say what they were saying, or better, to say what they would say today?

If you argue that the correct theological thing to say is that concupiscence is sin, I have to assume you want me to translate that into “Same-sex attraction is sin,” which is, as I argued last time, false. It might fall under the category of original sin, a particular mode of corruption. But it is not actual sin, in contemporary usage, “sin.”

Immediately, I can hear the objection: Matthew 5:28-29: “Anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart.” (In fact, I heard that objection at 5:30 this morning from one of my readers, directly prior to our F3 - Fitness, Fellowship, and Faith - workout.)

Distinguo. Whoops, I said no scholastic terminology! Let’s distinguish.

Jesus said that lusting after a woman is blameworthy - committing adultery in the heart. This is to say that inward acts, not only outward acts are sin. (After all, sometimes the only difference between the two is opportunity, as C.S. Lewis brilliantly made the point in Mere Christianity.) What Jesus does not say is that unchosen desires and the disposition to sexual attraction are automatically actual sin. In fact, I think most of us who have tried to steward our sexual attractions know the difference between being tempted, i.e., experiencing desire, and lusting, succumbing to that desire, if only internally.

The line of distinction between sin and misery is not, therefore, between outward acts of sin and everything else. On the contrary, not only outward acts of sin but even inward acts of sin, the will’s consent to succumb to temptation, are actual sin. But distinct from actual sin, both outward and inward, are the unbidden passions and desires that occasion temptation, as well as the capacity for and disposition to experience sinful desires. Theologically, this disposition can, after the fall, be called original sin, but it cannot be called “sin” in the contemporary sense, or “actual sin” in the theological terminology.

What is more, “sexual orientation” does not refer even to temptation, desire, or any instance of attraction. It refers to the fact, underlying all sexual desire, of which sex is even a potential object of one’s desire. Think of it as a particular form that original sin can take in some people and not others. Anyone who has experienced puberty knows that it is not something that is subject to our will. It just happens. (Unless it doesn’t. In the linked video, James Linehan details the experience of lacking a natural puberty, which only further reveals that puberty and the desires resulting from it are things given, not willed.)

In turn, which sex is the object of our erotic desire after puberty is something that just happens or is given. It’s like being dealt a hand of cards, and finding that they are all the same suit (and a different suit than one’s compatriots). “It’s not that I’m really into spades, and that’s why I only play spades. It’s all I was given.”

3. Nature and Modern Scientific Discovery

That brings me to a further question about the language of “sexual orientation,” modern science, and the theology of nature. Mason objected to me that “sexual orientation” is a modern category. Further, it’s a modern category that treats as natural something that, on a Christian account, is unnatural. A Christian account of nature should distinguish natural desire from unnatural, as Paul does in Romans 1. The account of what is natural is therefore one with some normative edge; it points to the ideal of our created nature, rather than to broken alternatives that arise after the fall.

I want to say two things in response: 1) Modern, and scientific, categories can be correct, since they are derived from the systematic empirical observation of nature; and 2) Our category of nature in Christian theology must include nature in its post-fall condition, sinful, fallen nature.

To the first one, I have long encountered, in philosophy and Catholic philosophy in particular, the idea that there is a difference between modern and pre-modern thought, and between the modern category of nature and the pre-modern. (A significant instance would be Edward Feser, e.g., The Last Superstition, his readable, Thomist takedown of the New Atheists.) As readers of this newsletter will know, I object to the idea that different people, with different religious or ideological worldviews, have different categories or concepts. But I also object to the historicist idea that these concepts change from one era to another, especially across the boundary of modernity, which is often treated as an irreversible ideological change. (For example, by Douglas Murray, who wants to believe that his atheism is inevitable, even though he sees the value of Christianity.)

“Nature,” I submit, is a category that refers to the world every human being has encountered, such that the vast majority of people have possessed this concept, one and the same. I do have a lot to say about the modernist and scientistic restriction of nature to the purely factual, valueless, and mechanical. (For the bold, I recommend analytic philosopher John McDowell’s, “Two Sorts of Naturalism,” on this subject.) In contemporary scienstistic philosophy, “nature” is often taken to be the object of modern science, with the ideal of modern science being physics, such that “nature” is taken to be all and only that which can be described in the language of modern physics. However, that is not a novel concept of “nature”; that is a mistaken proposition or philosophy about nature.

In the same way, when I advocate the inclusion of the category of “nature” in Christian theology, I do not mean a nature that is unavailable to modern science. I do not mean that we should return to an exclusively pre-modern Scholastic philosophy of nature, leaving aside the advances of modern science. By “nature,” I mean the stuff that Aristotle, Scholastics, Newton, Einstein, and contemporary scientists all studied or study.

This means that contemporary science, in spite of its bracketing of teleological and moral questions, can deliver new results. And the category of “sexual orientation” in particular has arisen in the last century and a half as a result of the observation of nature by psychological and scientific methods. On top of that, ordinary, non-professional experience acquaints most of us with a distinction between heterosexual and homosexual people. Science and common experience, as well as Aristotelian and scholastic philosophy, acquaint us with nature.

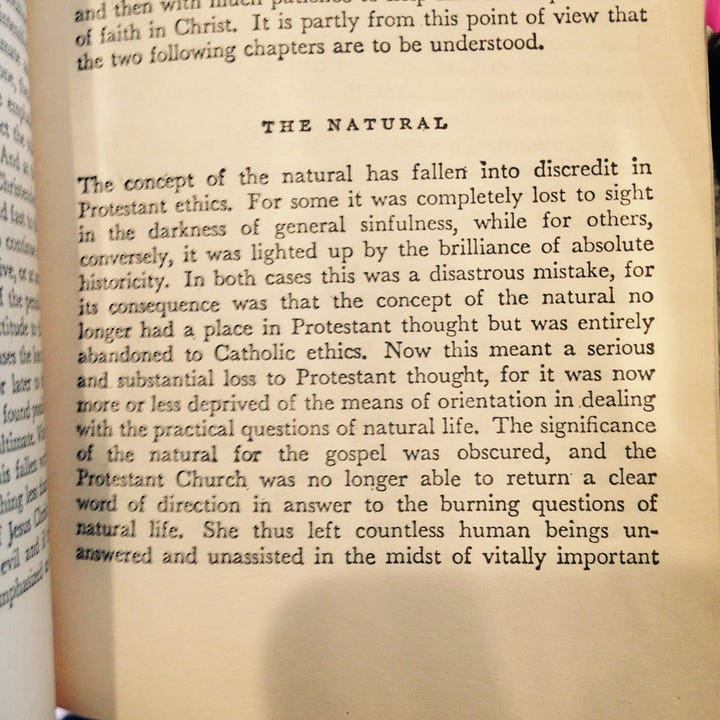

Now, this means that the category of nature is not limited to nature as created, to the ideal, or some such. But this is theologically crucial. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, in his Ethics, argued that Protestant theology had lost the theology of nature. He advocated the recovery of the category but also resisted, as I have, its reduction to the more biblical and pious-sounding word “creation.” No, it is nature, the stuff of this world, in its broken and fallen condition, that must be incorporated into Christian theology, not to mention assumed by the second person of the Trinity. Nature fallen includes both the created normative and ideal aspect and a broken and fallen, unnatural aspect. Paul said that men exchanging natural relations with women for those with men was unnatural. But he did not by this mean to deny that it could be part of sinful, fallen human nature, prior to human volition. In fact, he never discussed the very nature of same-sex orientation.

The theologically significant thing is, then, the difference between created nature and nature. And to bring things full circle, that difference is not exhausted by the category of sin. It also includes misery. And sin and misery are, in turn, intertwined in the ways that sin includes what is pre-volitional, that to which we are subject, and which we do not choose. In this, homosexuality is not unique; most of the rest of human psychology and experience is characterized by the same complexity of sin and misery. A truly Reformed Christian psychology would take account of all this and exhibit a kind of sympathy that is unfortunately uncommon among Reformed Christians today.

4. The Merciful Doctrine of Original Sin

Many of us think of the doctrines of original sin and the five-point Calvinist’s “total depravity” as harsh doctrines - rightly harsh. They express a negative view of human nature in contrast to the Enlightenment or Rousseauian view of human nature as intrinsically good. (The number of philosophical errors in that last sentence alone makes me shiver.)

On the contrary, atheist Alain de Botton looks at the Christian doctrine of original sin and finds in it a basis, even in a secular view, for a sympathetic and understanding recognition of human weakness and imperfection. I would urge that we understand our own doctrines at least as well as this atheist philosopher.

What is more, I would urge that we try to understand ourselves in this way. We are no better than the same-sex attracted Christian who can’t help but think that “gay Christian” is an accurate description of him or herself. Likewise, for all of us, the doctrine of original sin does not mean that we are all absolutely terrible. On the contrary, we are, as the Catechism teaches, born into a state of sin and misery, where even our sin arises from unchosen temptations and the inheritance of original sin. We should view ourselves, and others, with corresponding sympathy and understanding.

Good thoughts here and much to agree with. Our theology of nature has to take into account that fallen nature is our day-to-day experience and recognizing that same-sex attraction is usually pre-volitional does help us to show compassion to people struggling with sin and/or misery.

I can see how it might be a hinderance to communicating with unbelievers to restrict the word "nature" to creation as designed/intended when it's commonly used to refer to the world as we experience it today which is fallen from the original design. Using "nature" to refer to the world as it is now in a fallen state and then using a modifier like "created" or "ideal" when referencing the unfallen natural order is one way to approach it. This allows you to use the word "nature" the way most unbelievers define it.

However, it seems misleading to use the unmodified word to refer to a modified natural order and then use a modifier to signify the unmodified order. It starts to form notions that fallenness is the baseline and unfallenness is the modification.

For example, it may be common in some regions to specify that you want "unsweetened tea" when you want tea without added sugar, but that's a misnomer because tea doesn't come naturally sweet and then go through an unsweetening process to become unsweetened; tea itself is not sweetened. It's more accurate to use "tea" to refer to the drink in its unmodified state, and then call it "sweet tea" when it's modified. It may seem like pointless pedantry but calling normal/natural tea "unsweetened" over time causes people to view natural tea without modification as in fact a deviation from the norm.

Applying this to the issue of same-sex attraction, I don't think it's an accident that Paul uses the unmodified "nature" to refer to the ideal, and then modifies it to refer to a fallen experience. He's not just trying to describe the world but he's trying to form our souls and help us become attuned to the ideal. Talking about human sexuality as designed in creation, labeling it "heterosexuality", and making it one of many "natural" orientations distributed out to human beings creates the same kind of misconceptions about human nature that "unsweetened tea" does about the nature of tea.

One more quick thing: I think you should explore the Greek semantic range of “temptation”. You’re wanting to restrict it to internal temptation, but I’d argue that’s more of an English evolution than a good sense of the Greek, which actually leans much more heavily on external factors, so that even circumstances (and in fact more often circumstances) are considered “temptation.”