1.

In the latest edition of First Things,

does the important work of reading and reviewing Jordan Peterson’s latest book, We Who Wrestle with God: Perceptions of the Divine.However, like so much Christian commentary on the Canadian psychologist, Roberts’ review is mainly critical of Peterson’s lack of objective belief in God. His pragmatist approach to religion, Roberts notes, falls short of evangelical faith.

But Christian readers might need to remind themselves that, though Peterson shares much of our vocabulary, he does not typically use the words with the same sense. … Beliefs are “true,” without regard to their correspondence to real states of affairs. … Peterson also seems to neglect the importance of actual convictions about the objective state of affairs.

Though I have heard this criticism of Peterson from a variety of sources, it puzzles me. As a student of analytic philosophy, my philosophical heroes all fall short of objective belief.

But I don’t read philosophers’ works to learn the content of the creeds. I read their works to learn why, in spite of their lack of religious faith, they nevertheless find metaphysical naturalism wanting.

When I read a philosopher, I’m not looking for belief. I’m looking for perceptions of the limits of naturalism.

My own articulation of that limit is straightforwardly theological: God exists. But from a philosopher, all I ask is to find grappling with the limitations of materialism to understand human, moral, and cosmic reality.

And by that measure, Peterson is the most successful public philosopher of our generation.

2.

If you compare Peterson to Billy Graham, Peterson will appear a religious skeptic.

But if you compare Peterson, as I do, to the great heterodox analytic philosophers of the last generation, Peterson fits right in.

Here’s what I see from some of my philosophical heroes:

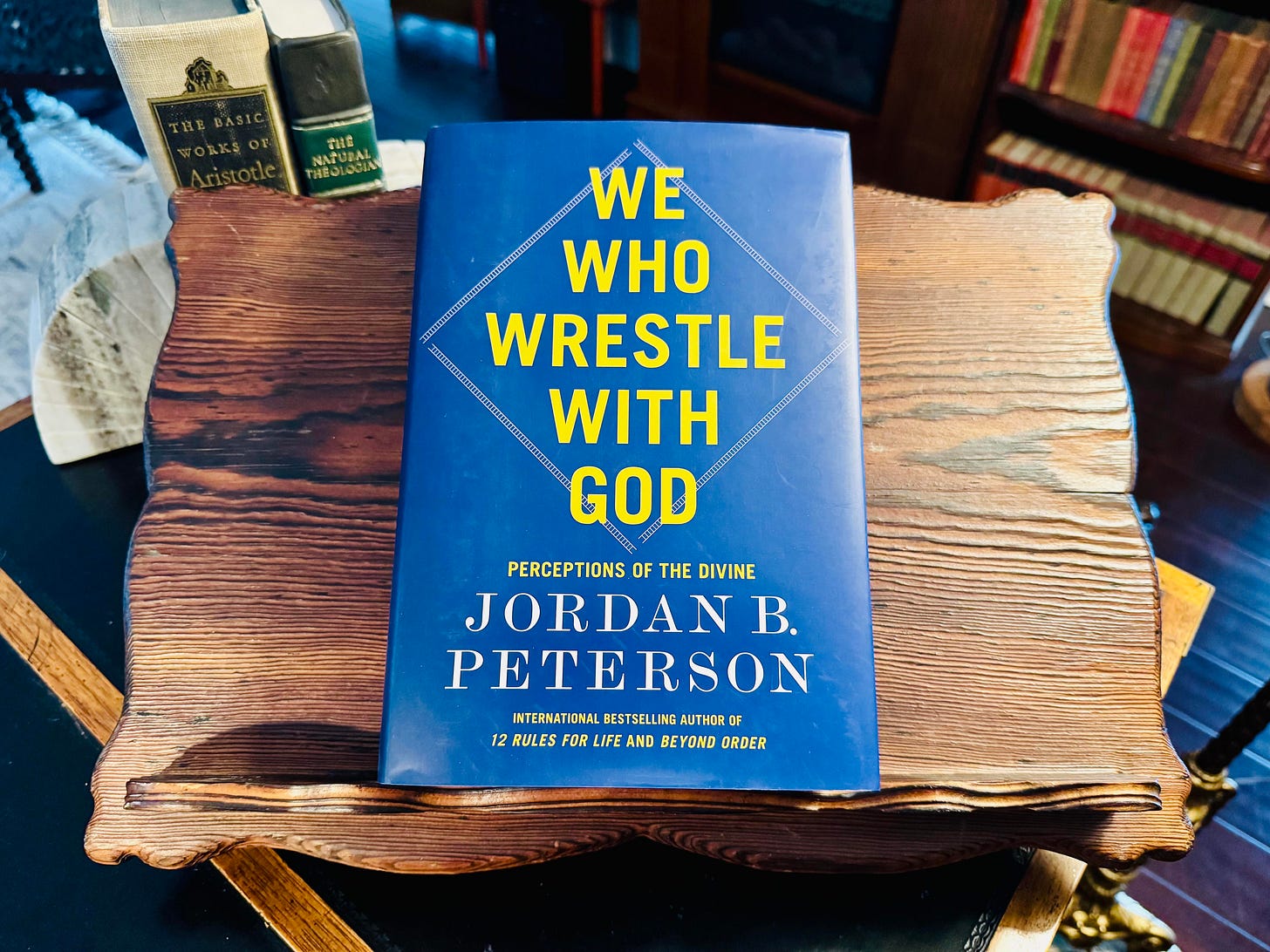

In Thomas Nagel, I find the irreducibility of the moral and practical dimension of life. While materialism would explain all from below, the fact there are moral and practical reasons to do and not do things is an irreducible phenomenon of human life. At the limit, Nagel finds that this undermines the materialist cosmology. But he is uncertain where this should lead him.

In John McDowell, I find a desire to vindicate the manifest image - the pre-scientific understanding of human beings. McDowell discovers the limits of scientism (“bald naturalism”) and argues that morality is not a projection but more like a perception of what is really there. McDowell thinks a “liberal” naturalism, one that is not reductionist, can accommodate the fullness of human and moral reality.

After an earlier positivist phase in his career, Hilary Putnam had the same emphases. He explicitly tied his vindication of common sense to the American tradition of pragmatism. He sympathizes with common-sense and with religion, while being unable to believe himself. In this, he’s much like the king of pragmatism, William James.

This is all I look for in a philosopher. I do not look for an out-and-out practitioner of metaphysical natural theology or natural law.

3.

Academic philosophers and psychologists share a background-theory of scientific materialism. I identify the good kind of philosopher by a willingness to wrestle with the impossibility of stably holding this perspective of ourselves.

The bad kind of philosopher is happy to debunk common-sense, religion, and folk psychology (the idea that people possess beliefs and desires, which neurophysical reductionists challenge). He is content with his materialism.

The good kind of analytic philosopher is not a dualist or immaterialist (with rare exception). He is someone who is discontent with his materialism. It is these philosophers that are best attuned to the limitations of science in understanding our world.

This is where I locate Peterson. His background theory is still evolutionary materialism. But he is discontent with the implications of this view.

(He has also indicated in interviews that evolutionary materialism may not be the whole truth.)

Philosophically, this makes Peterson a pragmatist, but not in a reductionist, debunking kind of way (“truth is just what works”). Rather, in a pre-metaphysical, bunking kind of way: Material science gives us truth, but there’s this other dimension of things, what works, and what matters, that is irreducible and cries out for respect, if not metaphysical explanation.

(Peterson once questioned materialism, saying, “Matter is not all that exists. What matters also exists.”)

In this, Peterson mirrors my previous philosophical hero, Roger Scruton (from whom I got the language of “bunking”). These figures are allies of Christians, though not the same as us. Their role in discourse is different. To criticize them for this difference is to miss the point.

(If I criticized John McDowell or Thomas Nagel for not being a Christian, that would be a bit bizarre. See 1 Corinthians 5:12-13.)

4.

Perhaps the frustration comes from Christians’ sense that Peterson is on the brink of faith himself, or that he so often uses our terminology, only to retreat to pragmatist and psychological interpretations of it. But the very title of Peterson’s book is, “We Who Wrestle with God.”

Peterson’s way of wrestling with God is to ask what of the biblical story and world religions would be true even if they did not objectively happen. Given the limitations of Darwinian materialism and Jungian psychology, what would we still retain? The New Atheists answered, “Nothing.” Peterson answers, “Much.”

The fruit this has borne, from my observation, is that many young secular people are reconsidering faith. This begins with Peterson, precisely because he is saying that Christianity would be worth following even if it wasn’t exactly true. But for most people, Peterson’s wife and daughter included, this leads to the further question, “But is it true?”

Peterson himself fends off this question, worried that it would undermine the search for wisdom from biblical texts. That worry is not unwarranted. But when pressed on it, he even answered Alex O’Connor’s question about the empty tomb by saying he thinks it was empty. Peterson may be considering these further questions behind closed doors.

However, the main public function of Peterson’s work is to argue that, even if Christianity is not straightforwardly true, it still merits our attention.

And given that many of our contemporaries do not yet think it true, we Christians should be grateful for Peterson’s work preparing the way.

5.

Roberts’ review begins with a quotation from C. S. Lewis, one that seems almost prophetic:

A man who disbelieved the Christian story as fact but continually fed on it as myth would, perhaps, be more spiritually alive than one who assented and did not think much about it.

(Lewis, “Myth Became Fact,” 1944)

What Jordan Peterson offers us Christians is the possibility of adding to factual belief training in how to “continually feed on it as myth.” May we be found willing to partake.

For more on Peterson, check out my and Anna’s previous article after attending Peterson’s “We Who Wrestle with God” Tour:

Jordan Peterson: He Who Wrestles With God

The evangelical takes on Jordan Peterson’s “We Who Wrestle With God” tour are coming out. Jake Meador attended Peterson’s lecture in Omaha and says that Peterson’s ideology is focused on excellence to the exclusion of mercy. Aaron Renn attended in Indianapolis and

Roberts said "Peterson also seems to neglect the importance of actual convictions about the objective state of affairs."

I don't think it is accurate or fair to say that Roberts is criticizing Peterson for not being a Christian believer. That is not what that quote says.

Thank you for sharing these thoughts. I have Peterson's new book and am about to read it and so I've been checking out the reviews to get a sense of where evangelicals are at with it and have been disappointed (haven't read Alastair's yet). My suspicison has been that evangelicals are missing the mark and that Peterson probably fits into a more allegorical sense of scripture seems to be confirmed by what you say in this post. Looking forward to reading the book now.