What Is My Dissertation About? Bertrand Russell and the Objects of Thought

My Ph.D. is a test of the thesis that there can be common ground between believers and unbelievers. One of those points of common ground is the reality of objective truth.

This week, I’ll be presenting at a philosophy conference, called Collaborations, which features collaborative efforts of professors with graduate students. My professor was invited to participate, and he kindly chose to present on the topic of my forthcoming dissertation. He and I have been working together for over a year now to settle on and understand the issue I’ll be considering in my dissertation: The question of the objects of thought.

Given that my dissertation prospectus is also due this month, I have a lot on my plate. But I’m going to try, in this post, to summarize what my dissertation will be about, pending committee-approval. A friend and reader quizzed me on this over the weekend, and it was very helpful to explain it to him. I’ll try to recreate here what I said to him.

Presuppositionalism and Mediated Knowing

Let’s start from a topic about which I’ve written and which is central to this newsletter. According to Christian presuppositionalism, there is no ideologically neutral and conceptually-unfiltered way to apprehend the world. As a result, non-Christians apprehend it through an interpretive and conceptual lens of one or another philosophy, while Christians apprehend it through the framework of Christian dogmatic theology. What we see is a product of our conceptual framework.

By that same token, Christian and non-Christians have different concepts. We do not merely say different propositions about man, for example. We have different concepts of “man.” As a result, we really have no common ground, epistemologically, with unbelievers. We can’t even agree on the meanings of our terms.

Knowledge of the world, according to Christian presuppositionalism, comes by adopting the proper Christian conceptual framework, downloaded from the inerrant Bible, and looking at the world through those glasses.

Now, there can be no doubt that Christian presuppositionalists believe in truth, Absolute truth. They are realists, in that sense. But we know the real world by a process that is mediated, rather than direct and unmediated. We think or cognize or perceive objects by way of a conceptual framework that is not simply given in the objects themselves or by sense-experience. Picture this as an indirect process with three nodes: Subjects, concepts, objects.

(Once again, Christian presuppositionalists claim to be above and beyond all philosophy, but in simply recounting their view, we have had to attribute to them several philosophical views: What is commonly known as Kantianism (we only apprehend the world through a conceptual lens), realism, and indirect realism in particular, and mediational epistemology. See my eBook, 50 Errors of Christian Presuppositionalism, for more.)

According to my dissertation, presuppositionalists are thereby subject to a philosophy that is the target of my dissertation, Neo-Fregeanism. I will say more about this, but one of its tenets is the mediational epistemology of indirect realism.

In the realm of theological epistemology, I have wanted to argue that this is the wrong epistemology for a realist orthodox Christianity. We should prefer an empiricism that is direct realist. On that view, all human beings have cognitive access to the world, man, and God, and the world, man, and God are the objects of our theological disagreements. We do not have different “concepts” of these things. We say different things, or “propositions,” about the same objects, with which we are all acquainted. We do have common ground with unbelievers, and it is only in virtue of that common ground that we can communicate with one another, and that any of us can be accountable to God. Direct realism provides the “point of contact,” “common ground with unbelievers,” and all of the other fabled categories of mid-twentieth-century theological epistemology (the discourse in which Bavinck, Kuyper, Barth, Brunner, Van Til, and Clark all had their place).

Analytic Philosophy’s Immaterial Objects

From the realm of theological epistemology, we move to Christian analytic philosophy. As my dissent from Christian presuppositionalism became more confirmed, my interest in Christian philosophy blossomed. As it happens, there is in academic philosophy a received way in which Christians can participate in philosophy. It is inherited from Alvin Plantinga and is Christian analytic philosophy. As it happens, Christian analytic philosophy is far from reliably orthodox and is beholden to a whole range of dogmas peculiar to its practitioners. I have detailed those in the article below, but let me highlight the relevant ones here.

American academic philosophy in the 1950’s was quite secular, more so than today. That was the heyday of logical positivism, but the academy has expanded since, though many of its quarters are still quite secular. In that context, Alvin Plantinga entered academic philosophy (along with fellow travelers like Nicholas Wolterstorff). Bringing with them a soft form of Kuyperian Christian presuppositionalism, they pioneered an approach to academic philosophy that question secular dogmas while adopting a certain logical and linguistic approach to fit in with the analytic philosophical milieu.

Much of secular analytic philosophy prides itself on possessing a scientific worldview. But the analytic philosopher’s scientific worldview is not your atheist uncle’s worldview. Most notably, it almost invariably includes a great number of immaterial objects. Because of these philosophers’ interests in logic, language, and mathematics, they introduce a number of entities that are not the material objects of science. (The material objects of science have already been superseded by space-time worms, by the way.) These include propositions, meanings, numbers, sets, and possible worlds.

Now Plantinga viewed this openness to the immaterial as an opening for supernaturalism. Secular analytic philosophy isn’t rigidly materialist, so who can really object if we bring in God as well? As a result, Christian analytic philosophy introduces God as yet another immaterial object to add to one’s “ontology” (the things one believes exist).

Of course, in doing so, one accepts the secular philosopher’s account of these many immaterial entities which had no settled place in Christian thought or theology. As a result, one gets a kind of syncretism, adding the Christian God to the pantheon of the analytic philosopher’s immaterial entities.

There are several problems with this. One is that God is not really at all like the immaterial entities that analytic philosophers countenance. In the main, the immaterial entities analytic philosophers countenance are what are called “abstract objects.” This is little more than a marker that such objects are not really objects, or not in the same way as what G.E. Moore called “middle-sized dry goods,” the chairs and tables and glasses and shoes that surround us.

By contrast, Christians do not take God to be an abstract object, but a concrete, though immaterial entity. This means both that secular philosophers should not think that God is just more of the same: “We already believe in propositions and properties - why not believe in God?” and that Christians have no reason to be especially interested in abstract objects as Plantinga and Co. are. In short, atheists shouldn’t be our guide to the immaterial.

But more to the point of my dissertation is the question of why secular philosophers accept such abstract and immaterial entities as propositions, possible worlds, properties, meanings, sets, and numbers. And the answer is that it is part of their theory of semantics, that is, of the meaning of words. For instance, given that mathematics is a significant and ineradicable kind of human discourse, its terms must be meaningful, chiefly its numerals must designate numbers. If there weren’t any numbers to designate, mathematics could hardly be stating truths about numbers and their relations.

Likewise, we talk about things like what someone said, what he meant, what she is thinking, and so on. We say that, “Snow is white,” “La neige est blanc,” and “Schnee ist weiss,” all say the same thing, just in different languages. What kind of thing is that? A proposition, analytic philosophers say. And similarly for other kinds of abstract semantic objects. We come to identify these objects as already present in our discourse about our own language and ineradicable from it.

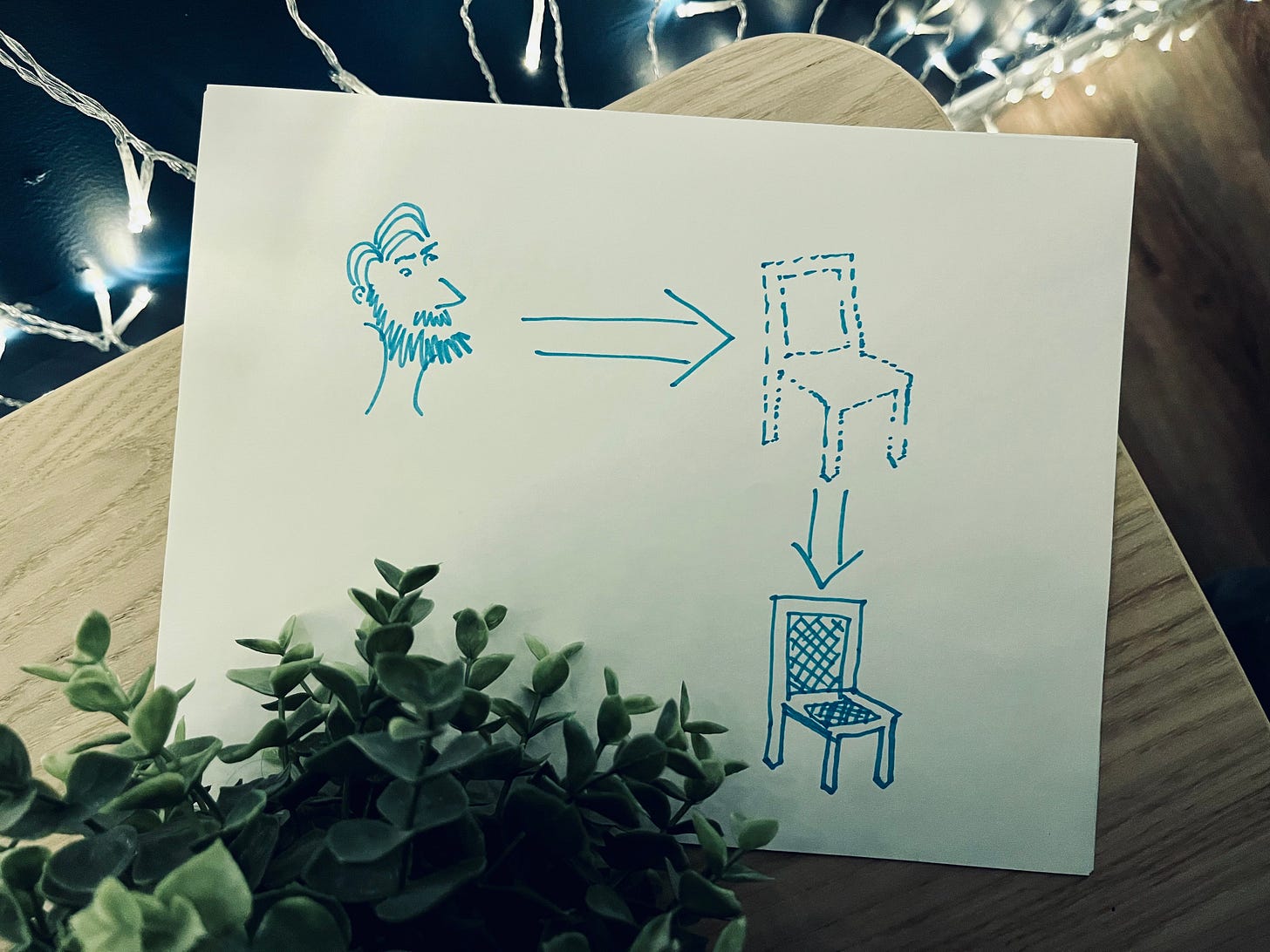

But in a new way, this account of the meaning of words introduces a theory of indirect realism, with the same three nodes. We think about objects in the world only via these tertiary, intermediate things. We are never in direct cognitive relation to the world and its objects.

Plato, Russell, and the Philosophers of Language

That brings me to my dissertation prospectus. But first, a story.

The first course I took with my advisor, Scott Berman, was a course on Plato’s ethics. As I prepared to write a paper for Scott, I was reading through several papers on Plato by a scholar who happened to have been Scott’s dissertation supervisor, Terry Penner. Penner in several papers referenced an unpublished manuscript in which he would give a critique of contemporary analytic philosophy from the perspective of Platonic thought: Plato and the Philosophers of Language.

I was intrigued and asked Scott more about this. Scott thought he might have a copy of the manuscript in his office, though that has yet to surface. Instead, he found a file of the first chapter and sent it to me, and we contacted Penner himself, now in his nineties. Penner is still editing, and no, we haven’t received a manuscript yet!

Regardless, the thesis of the manuscript is one that Scott inherited and took up himself and transmitted to me. Combined with a reading of the single chapter, a dialogue between the founder of analytic philosophy, Gottlob Frege, and Plato, I had an understanding of where the critique was headed.

The critique was that there were some hidden assumptions of contemporary analytic philosophers inherited specifically from Frege that conflicted with the ancient realism (thought can know the world) of Plato. Chiefly, the problem was these intermediate objects that were taken to be essential intermediaries between thought and the world, providing the meaning of words and the content of thought. By contrast, a theory of meaning and thought inspired by Plato would take it that thought can have direct cognition of the objects of the world, and that some of our words mean the objects themselves, without intermediary.

This view is called direct realism, that the mind can know the world without an intermediary, or by its detractors, naïve realism. But the theory of word-meaning, that some words mean simply the object or kind of object to which they refer, is inspired by another of the founders of analytic philosophy, Bertrand Russell. And that is a name with which my readers may already be familiar.

Russell wanted a theory of thought and meaning that grounded the ideas of objective truth and the possibility of knowledge. This separated him from anyone who took it that our thought could never be more than our own subjective perspective, which had its representatives in the early twentieth-century as it does now. Russell’s stand for objective truth reminds me of how Richard Dawkins once said something to the effect that, if someone doesn’t believe in objective truth, you really don’t want them as, for example, the pilot in the cockpit. Objective truth is quite important to a certain class of British atheists.

An Experiment in Christian Realism

This brings me back to my initial discussion of Christian presuppositionalism. My professor is also not a Christian, though not an atheist per se. But for me, this Ph.D. is a test of the thesis that there can be common ground between believers and unbelievers. One of those points of common ground is the reality of objective truth. Both my professor and I believe that what we are talking about when we talk philosophy is how things really are in the world. We can’t each have our own subjective perspective and simply go our separate ways. Our words bear on reality, and where they differ, we disagree, and someone is wrong, and, at best, only one of us can be right.

Admittedly, there are many who don’t share this concern for objective truth. Presuppositionalists will use this to say, “See, there’s no common ground with unbelievers!” As if Christians didn’t think they were wrong! We don’t have to grant that unbelievers have no awareness of truth just because a group of them pretend not to believe in the possibility of objective truth. Because there is objective truth, these subjectivists and postmodernists are simply wrong about it. The objectivist atheist is admitting the reality of objective truth and the common ground that there is between us all. “Common ground” between believers and unbelievers doesn’t mean that unbelievers hold the right positions on a bunch of issues. It means that they are in touch with the same worldly reality that we are, such that at least some, through the practice of philosophy, are able to admit the truth of some of what the Bible says about the world.

And this is really the point of my doing this Ph.D. on this topic. Christianity is something that is true of the world, the world that we are all in, that we all share as common ground. Christianity is not just another subjective perspective among others that you can only know if you simply assume Christian presuppositions. I want Christians to think and talk this way. It results in a less anxious mode of interaction with the world. I don’t have to worry that people will inevitably head in a godless direction if they think for themselves or experience the world in an unfiltered way. In fact, I want people to come into contact with reality more fully in order to be led to the creator of reality: Christian direct realism.

This was really well-written, Joel, and helped frame your thinking and project in clear and powerful ways. I very much look forward to more!

"In fact, I want people to come into contact with reality more fully in order to be led to the creator of reality: Christian direct realism."

Is this a typo? I really expected the creator of reality to be identified as God. (I see the lowercase "c" there.)

How does Christian direct realism create reality for the atheist? Isn't there a "common direct realism" that serves as the grounds for communication?