Giving Up on the "Jesus Juke": Four Secular Virtues Christians Must Practice

On faith and work

One of my first jobs was as a teacher for Kaplan Test Prep. My task was to teach math, reading, and writing for the ACT college entrance exam.

At the time, I was a student at a Christian college. I was as interested as anyone in integrating faith and learning. But what did that mean in a secular classroom?

As the weeks went by, I faithfully taught the content from the Kaplan curriculum, helping high school students refresh their knowledge of a variety of fields. I called on my secular competence in college entrance exams.

The final week, I began to daydream of finishing up the final day of class and, after, completing the course material, inviting the students to stay for a few words from me. I would launch into a brief, but heartfelt gospel presentation. Hopefully, in this way, I could improve more than their minds - the eternal state of their souls.

But I didn’t do it.

Instead, as I wrapped up, I heard one of the students chime in that this was one of the best classes he had had. My teaching had been some of his favorite, and he really felt he had learned a number of things.

Did I chicken out?

Did I seek the favor of man instead of God’s?

Did I care for the students’ minds but not their souls?

Did I just rearrange some ships on the Titanic?

On reflection, I don’t think so. Instead, I think I learned one of the most central lessons about faith and secular work: Not every secular action must end with a “Jesus juke.”

Secret Faith

In Secret Faith in the Public Square, Jonathan Malesic argues something similar, but in controversial terms: We should hide our Christian identity in the public realm.

Malesic defends this advice in part by reference to Christ’s words not to “let your left hand know what your right hand is doing” (Matthew 6:3). To advertise our Christian identity is to be too self-aware of one’s own purported righteousness. It is to seek an earthly reward rather than a heavenly one.

But, someone will object, being known as a Christian is not a status-boost in our current society. To hide one’s Christian identity would therefore be to hide one’s light under a bushel, to fear to bear the name of Christ before men.

There are several things to say in reply:

Christ is speaking of your own awareness of your actions.

In this teaching, Jesus is not speaking about seeking to be thought righteous by others - he considered that in the previous verse (Matt 6:2). He is saying that you should refrain from being aware even of the virtue of your own actions. In other words, to self-consciously think, “I am being a really good Christian by doing x,” is already to succumb to Pharisaism and self-righteousness.

You want the other to think that being Christian is a positive.

The intent of making someone know that you’re a Christian in public life is to make them think that being a Christian does make you a better person: “See, I am honest in my dealings because I’m an upstanding church-goer.” But that means that, eventually anyway, you want the other person to think highly of you for being a Christian.

This is going to seem paradoxical, because don’t we want people to see our good works and glorify our Father who is in heaven?

Absolutely yes - but the temptations of self-righteousness, Malesic argues, are right around the corner. It is one thing to “shine, make ’em wonder whatcha got”; it is another to announce one’s Christian presence with trumpets, bracelets, t-shirts, or Bibles.

Natural Goodness

But there’s more. Many, if not most of the actions we take in public life are acts of natural virtue, not theological virtue. What do I mean? Acts of natural virtue are acts that exemplify the virtue of justice; we do our duty, nothing more. “And if you love those who love you, what credit is it to you?” (Matthew 5:46).

Sajan George, managing partner at Praxis, laid out a helpful taxonomy of secular actions in a recent interview. You have 1) the exploitative, 2) the ethical, and 3) the redemptive.

In the exploitative realm, you are fighting for market share, and there is an “I win-you lose” relationship. In the ethical realm, by God’s common grace, people relate in a “win-win” way. But in the redemptive realm, “Christians are called…to be more than just ethical.” In this realm, the principle is “I lose-you win,” or better, “I sacrifice, you win.”

Now my argument is that Christian action must operate in all three realms - though qualifying that the first realm is one of self-interest or prudence, and not necessarily always of immoral exploitation.

The arguments of radical Christianity tend to pit the 2nd and 3rd realms against the first; see my recent critique of Paul Kingsnorth and the stream of radical Christianity. (Think Tolstoy, Anabaptism, and certain elements of monasticism.)

When we operate in the first realm and even the second, we are performing acts of only natural goodness. Acts of natural goodness are the stuff of most jobs. We have to make money to provide for ourselves and our families. To make money, you have to have “market share” even just in having a job.

But we also want to operate ethically, in accord with natural virtue. We want to exhibit the virtues of justice, temperance, courage, and prudence. In doing so, we are not yet letting our light shine before men. But we are doing things that are good, if not perfect.

Spiritual Dissatisfaction with the Natural

But in just doing our jobs, doing acts of natural virtue, many of us feel spiritual dissatisfaction. We feel like this stuff doesn’t matter or falls short of ultimate importance. I know I have felt this dissatisfaction, which is part of what drove me toward ministry-related professions. (In doing so, I was guilty of, yes, Christian nihilism, on which…)

But that dissatisfaction is exactly the gnosticism we don't want to exhibit. Impatient with the material, we run toward the spiritual.

What, then, is our view of Christian duty? Is it only spiritual? Or does the temporal matter also?

The apostle James reminds us that we must attend to people’s physical needs and not their spiritual needs only: “If one of you says to them, ‘Go in peace; keep warm and well fed,’ but does nothing about their physical needs, what good is it?”

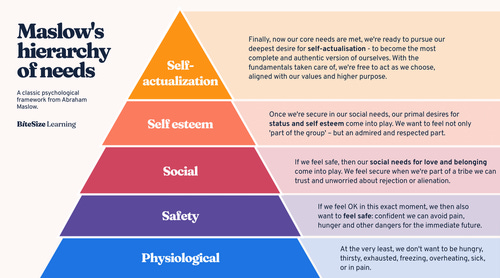

Many people take James’ teaching to be applicable only to the lower rungs of Maslow's hierarchy of needs: Food, water, shelter.

But implicit in James’ exhortation is the value of the whole realm of people's temporal well-being, from food to philosophy. These things are not ultimate, but they are penultimate. They are not the last things, but they are the things before the last things.

Secular Virtues

And that means that, even in the secular realm, we can exhibit virtue that is pleasing to God and ultimately serves the highest ends.

One of the ways we can see this is if we consider how redemptive, ethical, and prudential action are related. If we over-spiritualize, we will think that only redemptive activity is virtuous. But where does a person come by things to sacrifice? What does he or she have to sacrifice? If we absolutize redemptive action, we will conclude that only an heir can exercise Christian virtue.

If we broaden out our perspective, we will think that it is legitimate to exercise ethical virtue and prudence to accumulate resources, competence, and power in order to do good for others. This means that not only ethical but even self-interested or prudential action is necessary. That’s why I don’t think the first realm is only exploitative.

In fact, if you’re not a prudent business person, it will be difficult to run a business that abides by ethical practices. One will need to cut corners. Prudence is a foundation for exercising ethical concern and love for others.

For this reason, I think Christians need a reaffirmation of the lower secular virtues, not only Aristotle’s lofty justice, temperance, fortitude, and practical wisdom, but ambition, competence, and shrewdness.

Ambition

Consider ambition. In light of Christian humility, ambition can sound like a vice.

But “ambition” is too general a characterization to evaluate as a virtue or a vice: Ambition to do what?

Ambition, like intention, is a sine qua non of action. If someone had zero ambition, he would do nothing. Usually, when people are suspicious of ambition, what they really are suspicious of is a certain scale of action. They are comfortable with actions that are sufficiently small or moderate in scale. We laud small actions and condemn big ones.

The problem is that there is no ethical line between large and small. Virtue is a mean, but not an exact mathematical one. There is no a priori way to tell what aspiration is too grand, or which too mediocre.

In Aquinas’s virtue ethics, in fact, “ambition” does name a sin, an inordinate desire of honor. But there is an equal and opposing sin of pusillanimity that one can exhibit in shrinking back from action, or setting one’s sights too small.

(I would argue that, in our contemporary sense, “ambition” does not only denote “an inordinate desire for honor,” as Aquinas says, but also an ordinate one, proper ambition or aspiration.)

Emil Brunner affirms the same. He observes in Christians a tendency he calls, “Christian inwardness, … the obvious tendency of many earnest Christians to shrink from all external action” (Brunner, The Divine Imperative, 261-262.)

There are temptations in the neighborhood of a too great ambition - but there is also a sin of having too little ambition.

Competence

Competence arouses less suspicion. However, competence in a secular field requires secular knowledge; it exhibits human capacity and even self-reliance. Theological critiques of autonomous reason lie near at hand.

After all, competence in a particular field is not a specifically Christian virtue. Knowledge of the Bible may not add to one’s competence. Competence may be exhibited by one who lacks biblical knowledge and operates in a purely secular way. I, as a Christian, may learn from a competent practitioner who is devoid of theological virtue, but even ethical virtue as well.

But competence is not as godless as it appears. Knowing how God's world works is how you do good works. As I once wrote on Substack Notes (get the app): "You can't do good works if you don't know how the world works."

The way the world works can often feel alien and impersonal. If one works in information technology, or logistics, or data analysis, it can feel like one’s actions are unrelated to fulfilling the two greatest commandments, to love God, and to love others.

But the fact is, if we are to be effective and not merely to have good intentions, we must take action in the world of the technical and impersonal. Try to operate in the world without people with such expertise, and you quickly realize how little can be done without such intermediaries between intention and action.

Brunner exhorts: “Since God requires from us not merely volition but action, He requires us to enter into this ‘alien sphere,’ into this realm of the impersonal, and it is His will that we, as believers, shall prove ourselves within this sphere.”

It is in this “alien,” secular territory that God acts.

But the fact is, it's not actually alien; it's God's world. The secular is sacred.

Shrewdness

Shrewdness is another secular virtue, without which we cannot accomplish anything. Shrewdness, or prudence, is the virtue of knowing how to navigate this world and accomplish goals. Without shrewdness, we will simply be ineffective. There is no virtue in ineffectiveness. Whatever virtuous thing you hope to do will simply not be accomplished.

In one of his parables, Jesus commended the behavior of a dishonest manager. This man, on his way out after being discovered for graft, forgives several of his master’s debtors in order to land himself a cushy position later.

Jesus commends his behavior to his followers, saying, “For the sons of this world are more shrewd in dealing with their own generation than the sons of light” (Luke 16:8). Of course, Jesus encourages us to pursue not merely temporal but eternal ends. But he specifically commends the wielding of “unrighteous wealth” for eternal gain.

In context, the application is to alms-giving, a redemptive action. However, in the process, Jesus commends a virtue at the lowest tier of the natural virtues, quite ethically ambiguous. Sajan George’s label “exploitative” would certainly apply.

This goes to show that we Christians cannot retreat piously into the realm of good intentions. We must cultivate and exercise the competence and shrewdness to do what must be done.

(Read my academic paper on the parable of dishonest manager here. Below is an amazing AI-generated podcast summary of my article that Academia.edu offers.)

Human Judgment and Secular Wisdom

Since we are taking action in a realm in which secular knowledge is key, we enter a space of Christian and human disagreement. We cannot act in ways that are entirely uncontroversial. We must exercise human judgment, and we are inevitably responsible for these judgments.

There is a kind of biblicism that wishes to evade this kind of responsibility. It wants to do the biblical thing in each scenario. But the fact is, the right thing to do in the messy and complex world of technology, politics, economics, and more cannot simply be read off the pages of Scripture. We cannot exalt God’s revelation at the expense of the human responsibility to judge how best to serve God in neighbor in our concrete situation.

This means that for most work, the difference between Christian and non-Christian is not all-important. The line between good and evil actions cuts through the Christian and non-Christian population.

In my own profession, I find myself admiring my non-Christian advisor’s approach to philosophy, and to work and family, more than the average Christian philosopher’s. Among Christian analytic philosophers, I encounter a boring conformism and tiring careerism. With my professor, I share a desire to think independently and an Epicurean desire to sacrifice success for happiness.

Likewise, D.Z. Phillips, a Christian Wittgensteinian philosopher, once wrote of his ambivalence to the progress of the population of avowedly "Christian" philosophers. In response to Alvin Plantinga’s boosterism, he held that worldly success for the “Christian” cause might be counter-productive and that the best of philosophy could not be identified by a religious label. Plantinga’s paper was titled, “Advice to Christian Philosophers.” Phillips’ was titled, “Advice to Philosophers who are Christian.”

Christ said, "You shall know them by their fruits." Somewhere along the way, we said, "You shall know them by their label."

The same principle applies to philosophy as applies to plumbing. You don’t need a Christian plumber. Likewise, you don’t need a Christian philosopher, but a good one. My own aspiration as a Christian in philosophy is to be a recognizably good philosopher, by the standards of (at least one sector of) the secular guild.

All the Small Things

What, in conclusion, is my philosophy of Christian work and action?

It is to live a fully human and fully Christian life. We exemplify theological virtue without neglecting "all the small things," the natural and the ethical. We live a life which rises to the redemptive level, without ignoring the ethical and the prudential levels, but in fact by cultivating them.

We view the natural and ethical as preparatory to the theological. If I don’t exhibit these virtues, if I don’t cultivate human life and flourishing, why should anyway listen to my religious ramblings?

We must not call "Christian" things that are in fact secular, but which God has already called "good."

We must cultivate the lower, natural virtues of competence, ambition, and prudence; we must also cultivate the higher ethical virtues of practical wisdom, courage, justice, and temperance.

We seek moments of personal connection in which the ethical and even the redemptive break through, without abrogating the prudential and the technical.

It might sound as if I am departing from Christ’s teaching: “Whoever would save his life must lose it.” It sounds as if I am arguing that we can have our secular cake and eat an eternal one too.

On the contrary, if you wish to save your life, you must indeed lose it. That is the redemptive realm, the realm of sacrificial action, supererogatory action, and theological virtue.

But if you wish to lose your life - in Christ’s sense, to give it away sacrificially - you must have a life to give. You must rightly estimate your own capacities, cultivate them, learn how to “give it away.”

The act of "losing one's life to gain it” is also a long act. It lasts as long as we are ourselves given.

We must learn how to wield our nature, our capacities, our possessions, and our power for both temporal and eternal human flourishing. We do not need to abolish our own nature, ignore our own capacities, or devalue this physical existence.

God himself assumed our nature in order to lay his life down. As a result, we should not try to somehow escape our nature in order to lay our life down - to abandon all ambition, relinquish all possessions, foreswear all power.

We should not attempt to subtract from ourselves the nature that God added to himself.

God became incarnate in order that he might give himself sacrifically. We already are incarnate, and so our first act, on the road to sacrifice, is to acknowledge our vocation or calling. Who and where and what we are provides that outlines of God’s calling upon us.

The path of sacrifice begins in the realm of the secular.

The Verdict

Did I miss an opportunity, then, when I taught my test prep class well, but without sharing the gospel?

No, I loved my neighbor as myself. And, “Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me” (Matthew 25:40).

Before You Go:

My Music:

My Online Course:

What Is Theological Epistemology? An Introduction

I’m excited to offer my first course under the auspices of The Natural Theologian. The title and topic of the course is “Theological Epistemology,” the question of how Christians know and how God relates to human knowledge.

My YouTube Channel

(Click on image for link)

i enjoy your posts a lot

you look like nick mullen in the cover photo for your youtube thumbnail.

Ambition doesn't make sense as a virtue. Laziness, lack of intention or lack of ambition is more or less centered on a different orientation/direction. We're lazy if we don't want to do the dishes because we have a certain orientation to doing the dishes or something else is preoccuping our mind from getting them done. Ambition and it's contrary is an orientation issue, our natural drive is always present. In fact, when we look at this way, it seems odd to speak of it as something that should be cultivated instead of realized. If anything enthusiasm seems to be what your describing when it comes to lower and higher scales of ambition.