Delano Squires and Glenn Loury Talk Gay Marriage

If Christians believe that the moral law of God is private, like a private, corporate Slack channel, they reveal a sort of gnosticism and denial of natural revelation.

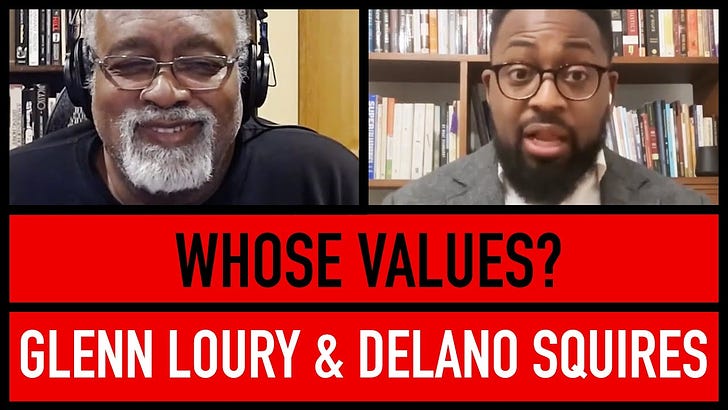

Yesterday, I watched this enjoyable discussion between Glenn Loury, an esteemed professor of sociology at Brown University, and prominent black conservative, and Delano Squires, a fellow at the Heritage Foundation and a black, Christian conservative.

Over the course of the interview, Squires had the opportunity to express and defend a Christian view of marriage and the family to Loury, who was at one time an evangelical Christian but retains sympathy for Christian morality.

This is what I heard as I listened: Delano Squires eloquently expressed the Christian position, but he failed adequately to defend it.

In the terminology I have been introducing, Squires adopted the rhetorical posture of a Christian coherentist, expressing the self-consistent doctrine of Christianity from Christian presuppositions, but failing to provide independent reasons to adopt those Christian conclusions or presuppositions.

Now, I want to maintain that Squires himself is based; but his defense of the Christian position hides the basis of his position in empirical and natural reality.

As a result, Loury objects, “But lots of people in our country don’t hold your Christian presuppositions. How can you impose your private religious views on the public?” In short, Loury is asking that laws over the common square be based on public reasons, reasons that all people can, in principle, know and accept.

Loury is correct to ask this. And Squires, by only defending conservative positions on strictly biblical bases, effectively concedes that Christianity is based on private judgment, rather than public reason. That is not a concession that should be made.

The listener may observe, as Squires launches into his expression of the biblical view, that it’s as if he’s not talking to Loury, but rather presenting him with a doctrinal statement of Christianity that he can take or leave. “This is what Christians think.” His words don’t have a grip on Loury’s mind, but depend on Loury having independent, public reasons to sympathize. Loury in fact has such reasons and argues sociologically and philosophically for social conservatism.

Why cannot Squires, the Christian conservative in the room, express the reasons why anyone should sympathize with the conclusions of a “biblical worldview?”

Rawlsian Liberalism and Public Reason

Loury’s request for public reasons for laws that will be imposed on the public has two potential philosophical bases. One, very probably at work, is Rawlsian liberalism. According to John Rawls, not only all religious views but all substantive moral views go beyond the purview of the state and of our public life. They are private. There is a neutral zone of reason, of public rationality in a liberal society that is not based on these private moral views but creates the framework within which people of different views can operate and live together.

Loury reacts to Squires’ presentation in a Rawlsian manner. “That’s your religious view, and it’s fine if you do that in private; but in the public arena, you need to have laws that are based on criteria all people accept, because they will apply to people who don’t share those views.”

Squires then rejects Rawlsianism in part, but accepts it in another part. He says, “Every state will impose a morality; the question is only which one.” Squires is correct. There is no independent sphere of right interaction between people of opposed moral views, at least when the moral differences include such things as who is a person, who has rights, what rights they have, and whether those rights include the denial of reality.

On the other hand, Squires implicitly concedes that Christianity is a private truth, especially that the moral claims Christianity makes are private truths. They cannot meet the bar of public reason. Everything Christianity claims is privately, specially revealed truth.

But this is false to the teaching of Christianity itself, which claims in general to be publicly epistemically accessible; more specifically, which claims that the morality it testifies to is a natural and generally epistemically accessible morality, available without the aid of special revelation.

Therefore, Squires is correct that some morality will be imposed, but he agrees with Rawlsian liberalism that reason, common human intellectual activity, cannot discern goodness and badness.

The Promulgation Principle

This is because there is another potential philosophical basis for the appeal for public rationality, one that Christianity should meet, rather than reject. That is a perennial principle of law, that a citizen of a polity cannot be held accountable for a law that has not been promulgated. If the moral law of God, of which Christianity speaks, has not been promulgated for all mankind, then they are not accountable for it. If the moral law of God is only available in principle but has been made epistemically inaccessible by the “noetic effects of sin,” then men are not accountable for it any longer.

The “noetic effects of sin” is one of the chief doctrines of Christian presuppositionalism, i.e., Christian coherentism, or of Common Grace Theology. It is the basis of “Christian worldview” thinking.

The way Christians engage in public discussion and debate reveals their theology of nature. If Christians believe that the moral law of God is private, like a private corporate Slack channel, they reveal a sort of gnosticism and denial of natural revelation. This is so even if, out of the other side of their mouth, they affirm the existence of general revelation. If all you can say to Glenn Loury about traditional marriage is, “The designer is the definer,” or “It says here in the Bible…,” you deny the general revelation of God, his natural law, written upon the heart. Thereby, you deny general moral accountability and leave Glenn Loury with an excuse.

The Christian approach to public reason rejects the Rawlsian basis for it, that religious and moral views are private, in favor of the Ancient and Christian legal basis, that laws must be promulgated. Rather than rejecting the standard that arguments should be acceptable to public reason, Christianity accepts the standard, and then, Christian morality meets the standard.

Christian Nominalism

Squires makes another Christian coherentist argument, but one that bleeds into even voluntarism and nominalism, the view that things have their nature by divine fiat and definition. As Squires summarizes concerning traditional marriage and the distinction between the sexes, “The designer is the definer.”

To which I say, “No! God is not the definer. He is, once again, the designer!”

In the creation narrative, there is no mention of God doing the work of Merriam-Webster. The mention of words and speech in Genesis involves God creating by speech, but Adam naming. Adam named the animals, not God. Things’ natures are evident in the things that have been made. God did not have to provide Adam with a divine dictionary.

Calling God a “definer” gives too much credit to the nominalism and postmodernism of our day. Again, on the basis of the doctrine of the “noetic effects of sin,” Christians deny the integrity and knowability of nature.

Based Belief: Jordan Peterson Against Cohabitation

As I survey the realm of public discourse, I find a dearth of Christian empirical engagement. As I described before, this drives me to look for a model in the secular sympathizers with Christianity, chief among them, Jordan Peterson.

By contrast with Delano Squires’ accurate statement but inadequate defense of Christian morality, Peterson stockpiles public reasons for avoiding cohabitation before marriage, in this clip:

The listener will observe that the full Christian conclusion at which Squires wants to arrive goes beyond Peterson’s argument. However, Peterson’s arguments are aimed to persuade, and not simply in terms of rhetorical strategy. They actually do persuade because they are based in reality, both social science and philosophy.

The Christian coherentist view paints a picture of a far-off mountaintop, the full height of supernaturalist Christian belief. But it does not guide people to or on the path up the mountain. Peterson’s arguments do not betray, for they do not assume, their destination. But they walk the listener along a path from a worse place to a better one.

Christian public engagement too often displays a sort of anxiety that careful, tempered thought and argumentation may not lead to the right conclusion. But would someone think this unless he were himself uncertain that thinking carefully and at length led to Christian conclusions? There is a sort of anti-intellectual pietism at work here, and it is not the best public witness to Christianity or the moral law of God.

The people of Israel were supposed to be a light to the nations. By any account, they ended up keeping the law of God for themselves. The work of Christianity was, largely, the spreading of the knowledge of God to the Gentiles, to the rest of the world. We must avoid a new Pharisaism that keeps Christianity for the Christians. If we deny a common starting-point for human thought, we deny the world any sort of on-ramp to Christianity. We pull up the ladder behind us, as if no public reasons had a role in persuading us to be Christians. We ought to display a greater intellectual generosity as Christians. What we have received, let us give to others.