Against First Things: Our political arguments should be secular

Why Oren Cass is right, and Rusty Reno is wrong

Vignette 1

“Hey, Professor. Are there any secular arguments against gay marriage? Or are there only biblical arguments?”

The late-career, Christian college philosophy professor paused to think.

“Not any that I know of. There’s pretty much only a biblical argument for traditional marriage.”

So there’s nothing but a few Bible verses keeping us from becoming reasonable, secular liberals. Our faith is nothing but irrational clinging.

Vignette 2

“Cornelius Van Til teaches that, while there is a natural law and general revelation, you’re giving in to autonomous man if you try to make any secular argument for morality or God.”

A hand is raised.

“But isn’t the natural law God’s law? How could appealing to it be giving in to a law of man’s own creation?”

“Well, people suppress the truth in unrighteousness; they don’t actually accept natural law arguments.”

“So we can say what exactly in conversation with an unbeliever? Nothing but, ‘Believe?’”

In which even the Catholics go fideist on me

I detect a pattern in Christian circles. Whether from apathy or zeal, we treat Christian truth-claims as incommunicable to non-Christians in secular terms.

Encountering this repeatedly, I eventually turned to Catholic natural lawyers for guidance. Yet now, even the Catholics are disappointing me.

In the October edition of First Things, Oren Cass writes, “By anchoring our account of virtue in an explicitly religious foundation, conservatives weaken our own cause, quiet our own voice. … The moment is one of…opportunity…if we have the courage to re-enter the moral arena and fight on broadly accessible and popular terms for what we know to be eternally true.”

Cass should know. A political economist whose thinking has led him into alignment with Catholic social teaching, Cass regrets to say that “religion just never ‘stuck’ for him.” But he hopes that his voice can help the cause of Christian morality, by encouraging us to “make the moral case for a politics of virtue,” and not only, “an unpopular theological case.”

What do my Catholic natural law heroes say in response?

“In order to determine ‘what is good,’ we must first determine ‘what is,’” writes Michael Hanby. In other words, we have to settle questions of metaphysics and religious conviction before we can do ethics or politics.

And Rusty Reno, editor of First Things, after granting some of Cass’s points, “Nevertheless, without religious voices in the public square, the political life of the West will be impoverished.”

Sigh. As if Cass had argued that religious people should be silent. No, he argued that we are silencing ourselves by making arguments on “an explicitly religious foundation.”

And Hanby’s objection is the Thomistic metaphysician’s version of Van Tillian presuppositionalism or Barthian fideism. “Until we get our metaphysics right, we can’t make any moral arguments!”

Ad Contra, at least one individual has come to an embrace of Catholic social teaching before getting his metaphysics straight: Oren Cass.

These responses betray an anxiety to prove the necessity of Christianity to political argument that is itself unnecessary.

Oren Cass is right: Political argument should be secular.

Metaphysics does not precede morality

Now, I admit that neither Hanby nor Reno has gone all the way to Protestant fideism. Dr. Hanby’s arguments are clearly inspired by the so-called Old Natural Law perspective, on which a Neo-Aristotelian or Thomist metaphysics is the logical prerequisite to natural law moral argumentation. This view strongly affirms that nature, apart from Scripture, can teach us moral truth.

But in insisting that moral argumentation is logically dependent on controversial Neo-Aristotelian metaphysics, Old Natural Lawyers make the same mistake as Protestant Presuppositionalists: They insist that the human order of knowing match the metaphysical order of being.

(For my academic treatment of the debate between Old and New Natural Law, check out my paper at Academia.edu.)

If God is the foundation of all things, then nature has its moral significance because of its divine origin. But this is not to say that no one can know of nature’s moral significance without first affirming its divine origin.

In the order of being, God is first. In the order of knowing, God is second.

Likewise, nature’s moral significance is indeed metaphysically dependent on its teleological ordering, as acknowledged in Aristotelian metaphysics. But this is not to say that no moral discourse can get started until we are all agreed on formal and final causality.

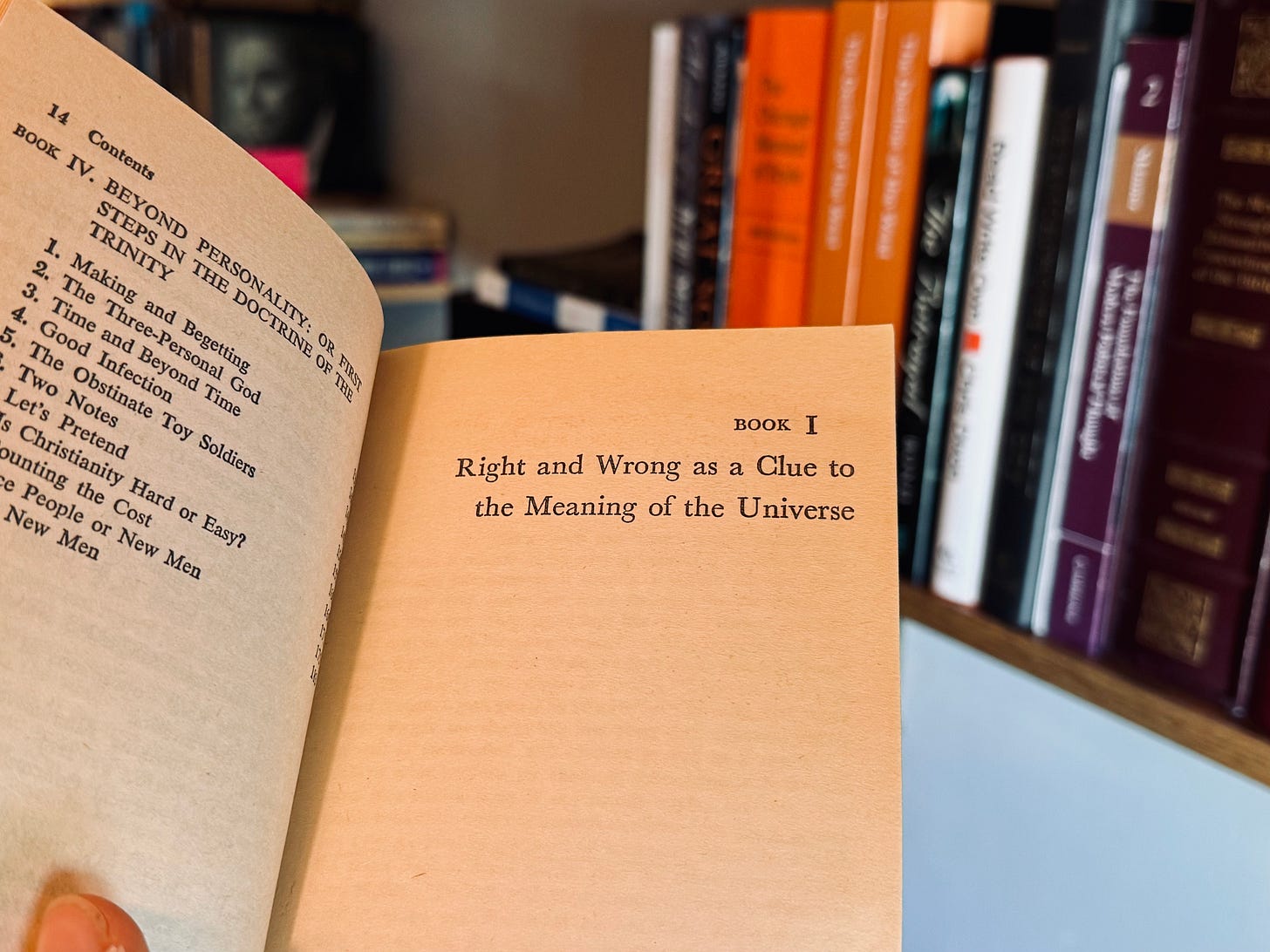

The first page of C. S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity provides the rebuttal to both Protestant Presuppositionalism and Old Natural Law. We are all engaged in moral discourse without being able to help it. And the moral law to which we keep appealing is not a law of nature in the descriptive sense, concerning what in fact happens. It is a law in a prescriptive sense, concerning what ought to be the case.

Morality is the first clue, as Lewis puts it, to the meaning of the universe. This is not to admit that morality does not require a metaphysical explanation. It does! That is what Lewis goes on to give. It is that we do not start from the metaphysical explanation of everything. We start where all humans start, and by the use of reason, begin to ask metaphysical questions about the unquestionable data of human life.

Morality, it is true, is not metaphysically freestanding. But Cass is, nevertheless, correct to say this: “Upholding virtue, honoring work, caring for those less fortunate, fulfilling obligations to one’s community–[these] are not innately religious. They are freestanding.”

We participate in morality and the orders of society whether religious or not. And these goods can be honored and cherished and understood even by those who haven’t yet engaged in much metaphysics.

Christian argument and action must be secular

Reno is not advancing Protestant fideism either. He grants Cass’s point about the secularity of much argumentation: “Natural reason also addresses moral questions, which bear on social policy.”

But Reno treats Cass’s argument as effectively in conflict with the founding mission of First Things, Richard John Neuhaus’s goal of ensuring “religious people a strong voice in American public life.” In this misunderstanding, I detect a faint whiff of that mixture known as “integralism,” the Catholic view that politics must ultimately be founded on explicit Catholic faith, transcending the merely natural law.

Even if Reno does not object for that reason, I know that some other Catholics would.

Yet Oren Cass is arguing that insistence on the religious character of public morality is itself in direct conflict with the mission of First Things. After saying that conservatives who root morality in religion “quiet our own voice,” he continues, “We conservatives have, perhaps inadvertently and with the best intentions for the nation’s moral fiber, done our part in bringing about the nation’s moral decay.”

Cass’s indictment is that a failure to make “a moral case for a politics of virtue” amounts to remaining outside of “the moral arena.”

In this Cass is correct. Beyond the pages of First Things, the English-speaking world has seen major developments in the “broadly accessible and popular” case for traditional social morality. Jordan Peterson began this process with his stand against forced speech and his lectures providing psychological and evolutionary interpretations of biblical teaching. For several years, an “Intellectual Dark Web” flourished doing the same. At present, a whole realm of podcasts - Modern Wisdom, Triggernometry, and even The Joe Rogan Experience - continues the discourse in which people of different political sympathies look at reality together and find moral wisdom and guidance apart from propositional belief in any of the major faiths.

Traditional sexual morality has found a secular champion in Louise Perry. The traditional family has found a defender in Rob Henderson. The intellectual case against gender ideology is being led by people like Helen Joyce, Abigail Shrier, and Alex Byrne, none of them believers. By basing their arguments on secular sources, these figures have a broad-based appeal, especially to current or former secular liberals.

There are examples of people of religious faith entering this discourse and playing by its rules. I think of Brad Wilcox, sociologist and author of Get Married. I think of Melissa Kearney, author of The Two-Parent Privilege. On a different dimension of ethics, I think of Nigel Biggar, who though a Christian ethicist and theologian, uses his secular expertise in philosophical ethics and history to help us reason about colonialism. By doing so, these Christians “re-enter the moral arena” in a way that is non-sectarian and that speaks to believers and unbelievers alike.

Again, Reno acknowledges the secular accessibility of much of individual and social morality. However, his worry that Cass’s argument would denude the public square again betrays a real misunderstanding.

Oren Cass is telling believers interested in the public square exactly what we need to hear: That we must address our arguments to public reason.

To enter the public square, religious voices must make a case that is truly public, that is, epistemically accessible to all people, no matter their private religious convictions.

Private faith and public reason

In making that final claim, some will hear me conceding the ground to political liberalism. Religious conviction is private and must be kept out of the public square lest we “impose our religion on others.”

But I would aver that the question is one of how religious conviction enters the public square, of how it has its public significance. I fear that our American Christian impulse in public action mirrors that of the Christian musical acts of yesteryear. There is an anxiety to brand our action as Christian, to show ourselves fearless to be identified with the name of Christ.

Dr. Jordan Peterson has received a lot of pressure to come down on whether he believes in God or Christianity. However, in his public lecture that I attended in St. Louis, he chastened the religious believers who pressure him in this for a kind of Pharisaism. We are eager for Peterson to cry “Lord, Lord,” and to do so on the street-corner. But Peterson urges that it is more important to act in a way that would make one worthy of saying “I believe in God.”

The same goes for Christian public action. As a friend of mine says, if I hold a door for someone and smile kindly, the urge to let the beneficiary of my kindness know that I’m kind because of Jesus is not entirely innocent. Reno writes of the courage of the faithful that, “Their arguments may be secular, but their spines are stiffened by faith.” I would only remind Reno that courage itself is a natural virtue. It is not only the arguments for virtue that are secular; it is the acts of virtue that are secular as well.

With regard to the religious motivation of our action, we would be wise not to “let our right hand know what our left hand is doing.” This is for the sake of others; if we present an action as secular and human, then people of any faith can be inspired to follow along, without needing first to change religions. But it is also for our own sakes; if we acknowledge the secularity of our action, there is a humility about the ordinariness of righteousness, and the fact that we have not yet entered the realm of the supererogatory, in which we can verify the presence of theological, in addition to natural virtue.

I think of Chris Rock’s rebuttal to those who boast, “I take care o’ my kids”:

“Yo’ supposed to take care o’ yo’ kids!”

The witness of the secular

Let me return to the vignettes at the opening of this essay. In one case, the moral claims of Christianity are presented as groundless, only susceptible of parochial religious justification and motivation. In the other, the moral claims of Christianity are presented as firmly grounded…in parochial religious justification and motivation, incommunicable to those outside the faith.

In either the apathetic variety of fideism or the overzealous one, I see a failure of the faithful to enter the public square. Those positions are at odds with the goal of Richard John Neuhaus. But likewise the attempts of Hanby, Reno, and others to insist on either the priority of metaphysics to morality or the religious character of public action implicitly recapitulate this fideist retreat.

Oren Cass is telling us that a great many non-believers are open to the moral claims of the Judeo-Christian tradition, so long as we provide secular argumentation for them. Oren Cass is joined by a great many others - the late Sir Roger Scruton, Dr. Jordan Peterson, Louise Perry, Rob Henderson, Chris Williamson, Konstantin Kisin, and I could continue - all of whom are making a better case for Judeo-Christian morality than many Jews and Christians. We should heed these unbelievers’ pleas that we speak persuasively.

My comfort, however, is that even if we fail to do so, the rocks will cry out - not to mention human biology, contemporary social science, and the human conscience, as they seem to have been doing.

Would that we would stop posing as denizens of the realm of supernature and, instead, “join with all nature in manifold witness.”

If you enjoyed that article, you’ll want to sign up for my Theological Epistemology course

If you’re interested in the questions of secular arguments for religious conclusions, you’ll want to sign up for my course on theological epistemology. A paid subscription to The Natural Theologian gives you access to video course lectures. Previous lectures have considered the spectrum of Christian approaches to faith and reason, the British Idealist roots of Cornelius Van Til’s presuppositionalism, and the epistemology of the great arguments for God’s existence.

In a forthcoming lecture, I’ll consider the question I raised on this essay about the relationship between the order of being and the order of knowing, the ordo essendi and the ordo cognoscendi. Hegel, Aquinas, Lewis, and Van Til will all be implicated!

Thanks for a thought-provoking essay. I think of Alasdair MacIntyre’s work and O. Carter Snead’s “What It Means to be Human” as exemplary in this regard.

Dogs know natural law FAR better than people do. Most dogs haven't read Aristotle or Aquinas.

The notion that reason comes before morality seems to be part of Catholic intellectual tradition. It's backwards. Reason is how we justify BREAKING natural law. Any decision at all can be defended validly by reason.